Go down to the Potter's House

Review: Thomas Commeraw at the New York Historical Society

Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Free Black Potter Thomas W. Commeraw. New-York Historical Society, January 27, 2023 through May 28, 2023. https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/crafting-freedom-thomas-commeraw1

Admission: Up to $22.00. Pay-as-you-wish on Fridays between 5:00-6:00 pm. (Chintzy; it’s a cramped space.)

Resource: A. Brandt Zipp. Commeraw's Stoneware. The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner. Sparks, MD: Crocker Farm, 2022.

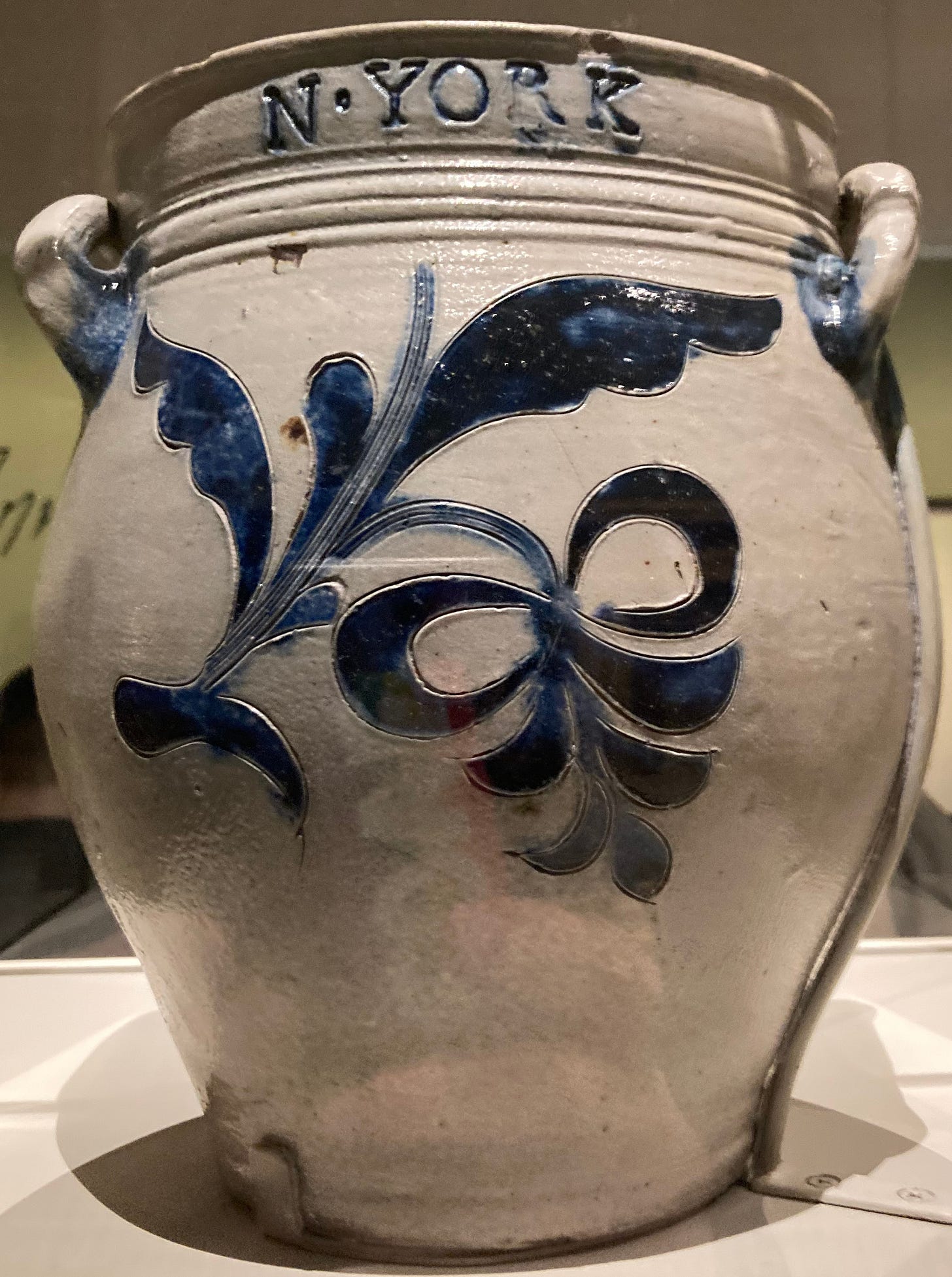

Not a jeremiad. There’s barely an adjective, enthusiastic or quarelsome, to be found in the signage for this tight, informative and dispassionate show, except on the topic of entrepreneurship. Thomas W. Commeraw was a Black man, a freed slave who established a potter’s kiln in New York City, at Corlears Hook, just below where Grand Street meets the East River today.

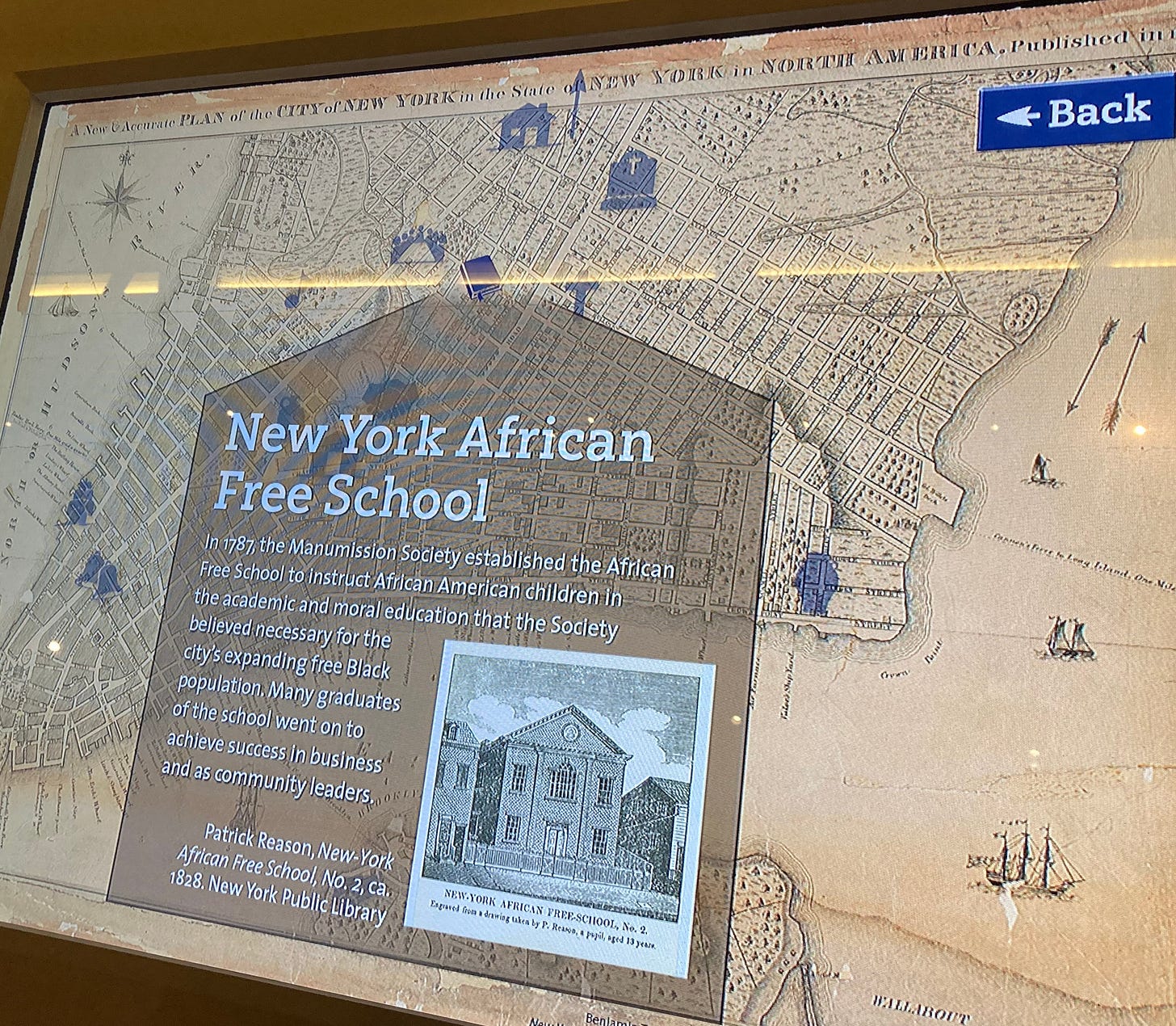

Commeraw was typical of the Black middle class striving to establish itself in the first decades of the nineteenth century, a time of rising equality for Blacks in the United States, even in New York State, which did not fully abolish slavery until 1817. In this telling Commeraw comes alive as a businessman, a congregant, a philanthropist, politically active — in other terms a sharp operative with plenty of energy. By some indications Blacks, in those days, were admired and resented for the same qualities and faults as Jews a century later:

And, as with Jews, it all came to naught. By 1820 Blacks in New York State were being gradually deprived of whatever rights they’d won. That same year Commeraw embarked with his family to found a colony of freed blacks in Africa. The venture collapsed and Commeraw returned to New York to die.

The Code of Ethics for museum professionals forbids curators and museum personnel from buying and selling artworks in a personal capacity, but the exhibition is indebted to A. Brandt Zipp, who first discovered Commeraw’s ancestry and wrote the imposing volume that accompanies this show. Zipp and his family run Crocker Farm, an auction house that’s self-described as the industry leader in selling antique American stoneware and redware pottery. Today, Crocker Farm is in a very good position: fears of repatriation and forged provenance have driven collectors toward local American art. At least one work in this show recently passed through the auction house.

This helps explain why the research behind this exhibition is so impressive. Dealers and auctioneers, if they want to maintain a blue-chip facade of reliability and integrity, have a greater stake in solid research on background and provenance than museum professionals, and they’re less likely than art historians to play with interpretation. And it’s good to visit a show devoted to an African American artist that doesn’t hit you over the head with self-serving bathos. The young people visiting this show seemed taken with its seriousness:

On the downside, it takes an entrepreneur to focus almost exclusively on the narrative of another, temporarily successful, Black, entrepreneur in America in the early part of the nineteenth century. Too much here is passed under silence—for instance, there is a jug produced by David Morgan, a White man who briefly worked with Commeraw:

What we are not told, is that the Morgan family had a long-established pottery business in New Jersey; that much of it depended on slaves, and that the head of the family owned a sloop that sailed up the Jersey coast ferrying potter’s clay and, on occasion, contraband slaves. (New Jersey did not abolish slavery until 1866.) In all likelihood the ship docked at Corlears Hook with fresh supplies. Potters with little capital would need some kind of credit to replenish their clay to produce pots yet unsold. David Morgan had connections with the suppliers. Was his partnership with Commeraw one too good to refuse?

“Cannot I do with you as this potter? saith the Lord. Behold, as the clay is in the potter’s hand, so are ye in mine hand, O house of Israel.” [Jeremiah 18, 6.]

As I’ve suggested elsewhere, it is impossible to disassociate the history of slavery in America from the history of the exploitation of labor. Whatever its intentions, this is the blind spot of this otherwise informative and challenging exhibition.

WOID XXIII-08