Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Through July 31, 2022. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2022/winslow-homer Winslow Homer. Force of Nature National Gallery of Art, London September 10, 2022 through January 8, 2023. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/winslow-homer-force-of-nature

“Whether art becomes politically relevant or indifferent. […] depends on the extent to which art's constructions and montages are at the same time de-montages. […] Art that succeeds in doing this has a prerogative: it may dismiss the question posed by political practitioners as to what it is up to and what its 'message' is.” Theodor Adorno.

It’s said that Georges Cuvier, the great paleontologist, could reconstitute a dinosaur from a dinosaur’s shinbone. That’s a good approach when dealing with the dinosaurs of Artpark, the critics and curators and museum directors who tell you what they think you need to know; from which you can conjecture what they think you need not know: what you need to know, in other terms.

The New York Times is always good for that. You needn’t read the copy, just check the headline, that’s where the Culture Desk tells you what the critic didn’t need to be told to tell you, which is how critics at the New York Times hold onto their job.1

And the headline for the Times’ review of Winslow Homer. Crosscurrents reads: “Winslow Homer: Radical Impressionist.” And it’s nonsense, but nonsense with a purpose: to reassure the customer about the product; to make Winslow Homer safe for consumption. And what could be safer than Impressionism? Just to show she got it right the critic adds:

“Homer’s acute observation of nature — light, atmosphere, weather — his use of wet-on-wet painting and tendency to paint from life qualify him as an Impressionist.”2

Never mind that Homer didn’t paint wet-on-wet, that he likely didn’t “paint from life,” or that “nature” and “atmosphere,” are very distinct categories. Never mind Homer’s simplified planes, antithetical to Impressionism; his preference for scumbles over glazes, even in those works that are insistently called “watercolors” but may well be gouache. Never mind Homer’s indifference to that reflected light whose effects had a determining influence on Impressionist theory and practice. The point of the article is to reassure the reader that Homer painted as an Impressionist does, by suggesting that Impressionism is primarily style and atmosphere over narrative.

If the Times would rather talk about Homer’s style it’s because his narrative is so unsettling. Homer paints Black people who are neither particularly happy nor particularly downtrodden; hunted animals from the hunted’s point of view; unforgiving seas; bodies entwined without a hint of the sexy. Most of all, he paints in cryptic narratives that seem designed to confuse the viewer. Homer himself seemed to enjoy baiting those who would look for the story:

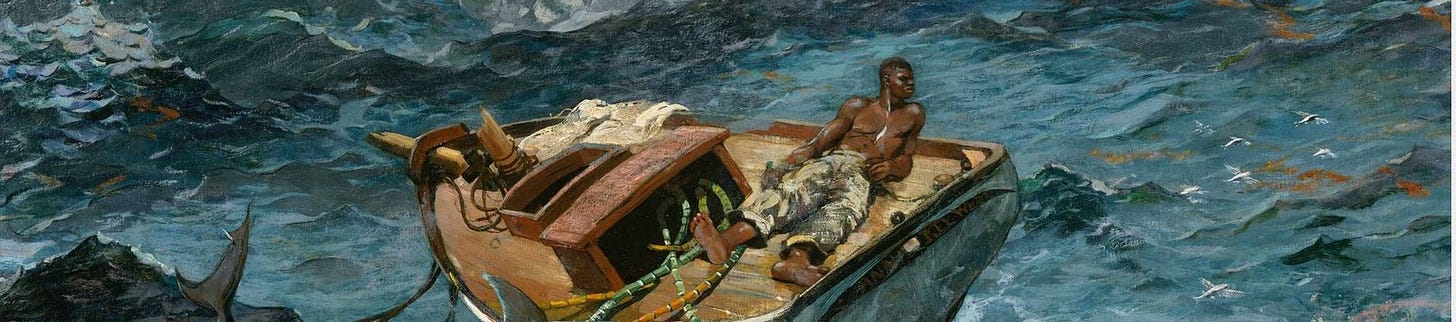

“I regret very much that I have painted a picture that requires any description. The boat & sharks are outside matters of little consequence. They have been blown out to sea by a hurricane. You can tell these ladies that the unfortunate negro who now is so dazed & parboiled, will be rescued & returned to his friends and home, & ever after live happily.”3

Homer’s attitude raises a justifiable fear among the viewers, even more so the critics and curators and art historians, that they may have no answers to his conundrums. Is it true that the white woman confronting a Black family Homer’s Visit from the Old Mistress “must now pay for their labor,” as the signage says? What about the Black man in The Gulf Stream, the painting that forms the center of this show? Is he about to be overwhelmed by sharks, or is it a typhoon? Is he an individual who happens to be Black, or does he stand for Black folks everywhere? Was Homer [gasp!] a racist? Where a curator asks, “How are we to interpret Homer’s assertion that the Gulf Stream’s details are ‘matters of very little consequence?’ the Times answers: those must be matters of very little consequence.4

That as well was the response of Henry James, the great nineteenth century novelist and passable critic of the arts, on his first view of Homer. Reviewing the work as early as 1875, James found himself troubled and fascinated by Homer’s dullness, as he saw it; fascinated enough to turn to it twice in his review. At least James was observant enough to note formal and painterly qualities that had little in common with those that would eventually be found in Impressionism:

“He sees not in lines, but in masses, in gross, broad masses. Things come already modeled to his eye. […] The want of grace, of intellectual detail, of reflected light, could hardly go further.”

Like the critic for the Times, however, James could not bring himself to see anything more than “a desire to be simply and nakedly pictorial,” adding: “We frankly confess that we detest his subjects.”5 For James as well, Homer’s narratives were “matters of very little consequence.” In the common view of critics at the time, realism was a form of materialism devoid of “literary” or idealized interpretation. A year later James would have a similar take on the French Impressionists. In a brief notice of the 2nd Salon des Indépendants he wrote,

“The young contributors to the exhibition of which I speak are partisans of unadorned reality […] To embrace them you must be provided with a plentiful absence of imagination.”6

James would eventually change his mind about Impressionism. Like the New York Times today he would use it as a foil for everything Homer stood for, only without projecting onto Homer all the virtues associated with Impressionism: lightness and grace and all those things associated with Europe; not subjects, but atmosphere; not popular culture, but elite Eurocentric culture; no emotionally charged narratives. In his last protracted visit to America James brought together all the strands of these conflicting sensibilities. After stumbling upon a collection of Impressionist paintings in a New England town he observed, “One hadn't quite known one was starved,” adding, “it was like the sudden trill of a nightingale.” Nightingales, of course, are not native to America; and James had in the preceding page established why the cultural equivalent of the nightingale is foreign, too:

“This apprehension that the ‘common man’ and the common woman have here their appointed paradise and sphere, and that the sign of it is the abeyance, on many a scene, of any wants, any tastes, any habits, any traditions but theirs.”7

This is the same arrogance of class James had applied to Homer decades earlier: “barbarously simple,” skilled at representing what he saw but devoid of higher vision, a mere craftsman set apart from those who “desire to be complex, literary, suggestive.”8

For James the dominant American culture was no Culture at all because it was unapologetically egalitarian. James, who was influenced by Hippolyte Taine’s theories that national geographies determined human behavior, suggests that Americans, being spontaneously egalitarian, are wired to reject the refinements of High Culture, which can only be imposed from above, by the kind of education the Times is ever eager to provide. I have argued elsewhere for the term “Repressionism” to designate the deceptive tendency that assigns civilizing values to Impressionism while denying its original biting and disruptive aspects,

“avoiding at any cost the complex and disturbing interpretations that the Painters of Modern Life brought to their representations....”9

Repressionism, then, would consist in appealing to painterly style and a realistic representation in order to deny and pass under silence the disturbing representational strategies that can be detected among the early Impressionists and Edward Manet, their master and precursor. Claude Digeon, one of the most influential and underestimated commentators on French intellectual life of the second half of the nineteenth century, similarly commented that many paintings of the times

“seem to... ‘lack a beyond,’ to require another angle... The reason being that they are built by antithesis to a thesis too well known: optimism, the Ideal. They want to shock, to attack, and their approach by means of simple observation with objective avoidance is the most effective one…”

« paraissent... “manquer d'au-delà”, appeler une seconde partie de tableau [...] La raison en est qu'elles sont construites par antithèse à une thèse trop bien connue, celle de l’optimisme, celle de l’“idéal” : elles veulent heurter, attaquer, et la méthode du simple constat à prévention objective est la plus efficace contre une esthétique moralisante. »

And goes on to quote a conservative critic:

“The most common sign by which I recognize the influence of the new spirit is the opinion, spread everywhere, that truth has an essentially relative character.”

« La marque la plus générale par où je reconnais l'influence de l'esprit nouveau, c'est cette opinion, partout répandue, que la vérité a un caractère essentiellement relatif. »10

A reaction that would not be out of place among the stalwarts of the New York Times.11

As early as 1866 a New York newspaper observed of Homer’s early effort, Near Andersonville, that the painting was “full of significance,” without concerning itself with what that significance was.12 Nevertheless, concern about significance was a commonplace reaction to a certain type of painting in the second half of the nineteenth century. Édouard Manet’s early critics were troubled, not by the implied meanings themselves, which they often blissfully ignored, but by the suspicion that other meanings were present that eluded them. One critic described Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe as a rébus, meaning a word puzzle to be assembled from apparently incompatible visual and verbal cues. The poet and littérateur Théophile Gautier wrote of Manet’s Young Woman with a Parrot, “We do not know whether a certain truth unknown to us is present in this picture.”13 That picture, ironically, is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where its playful allusion to Baroque systems of apperception continues to baffle. James, for his part, approached Eugène Delacroix with the same puzzlement:

"We concede that a painter may mean something, so long as no one can tell what he means.”14

Homer himself is often thought to have seen, and possibly learned, from Manet, the assumed leader of the French “materialist” school and eventual godfather of Impressionism, during a trip to Paris in 1867. The formal similarities between the two artists have often been noted, in particular the simplified planes, dark scumbles, affectless figures, and use of strokes of primary color to underline form—a technique closer to Delacroix than Manet. Nevertheless, it’s the similarities in symbolizing strategies that demand our attention, especially the fragmentation and dispersal of incompatible symbolic elements across the surface of the canvas. Just as Manet’s Old Musician is a concatenation of figures, each pointing toward a separate interpretation, so, too, in Homer’s magisterial Gulf Stream, the centerpiece of the Met exhibition, the man, the boat, the shark, the waterspout, all add up to several meanings in potential collision, leaving the audience to sort it out. For there are no superior meanings to be fished out for us by the privileged or enlightened viewer or critic, but instead a series of potential meanings, equally, democratically accessible. Needless to say this is a profoundly politicized approach. Needed to say, the democratization of the audience, as opposed to the parade of “democratic themes,” would be as troubling today for those elites who set themselves the privilege of educating the Masses, as it was in the nineteenth century on either side of the Atlantic. After all, what’s disturbing to some is is not the narratives themselves but their cryptic aspect—cryptic no doubt to some more than others.

The late French sociologist Bourdieu classified Manet, not as an initiator of styles, but as the initiator of a Révolution symbolique, meaning a revolution in symbolization. As a sociologist, Bourdieu drew attention to the social dynamics that made Manet’s system possible:

“A 'dispositionalist' aesthetic will into account the area of the possible at any given point in the evolution or situation of the artistic field.”

« L’esthétique ‘dispositionnaliste’ tient compte de l’espace des possibles à tel moment de la trajectoire ou de la situation du champ artistique. »15

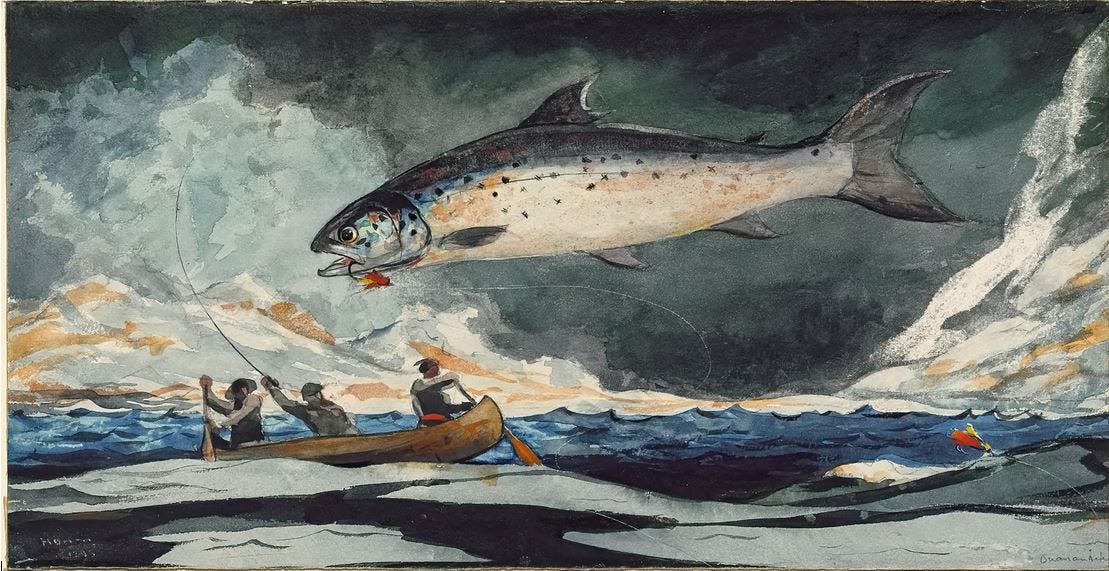

In Bourdieu’s system this translates into the insight that a painter—at least Manet—does not provide ready-made meanings to be plucked from his paintings by experts. Rather he sets up the canvas as a field of possibilities that are constrained and made possible by the dispositions of viewers, inviting each to participate in the elaboration of meanings. The canvas becomes the arena in which the back-and-forth of social interactions plays itself out. By Bourdieu’s logic Manet’s system cannot be treated as the brainchild of a unique genius but as a skillful elaboration and refinement of a symbolic system that is itself already present in the field of the possible. Meyer Shapiro has, among such possibles, identified popular visual culture as an important resource available to Courbet, as later to Manet: playing cards, popular images d’Épinal.16 Similar resources were available to Homer as well, witness Fish in a Good Pool, Saginaw River, whose perspective is straight out of a rural painted shop sign:

However, the likely impulse for the specific signifying system we have described originates in Homer’s early career as an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly during the American Civil War. An overwhelming number of Homer’s works read like the illustrations for which a magazine provides the story—except this time there is no magazine. The narrative remains to be written. Near Andersonville, the canvas that the Evening Post found to be “full of significance,” was one among Homer’s earlier attempts to move from illustrator to artist; perhaps being “full of significance” was a condition for that move. Sociologically speaking, an illustrator backs up the meanings of another; an artist is his own provider of meanings. In that vein, and for all its narrative crudeness, another precedent could be Richard Caton Woodville’s War News from Mexico [1848], which depicts the various reactions of a group of Americans to the announcement of US victories in Texas. At the forefront sits an African American who, clearly, does not share in the general jubilation.

Much has been made, much will be made again when this show travels to London, of Homer’s interest in “Nature,” in “natural phenomena” etc. Attention will be called, and rightly so, of conceptions of Nature in the nineteenth century: “Natural Selection;” “Nature Red in Tooth and Claw;” “Survival of the Fittest.” But we should bear in mind that Homer’s works are never landscapes: neither in the sense of “atmosphere,” nor harmony with Nature, nor even of equivalencies between natural phenomena and human psychology in the Romantic fashion. Here lies the difference, ultimately, between Homer’s work and the type of “Impressionism” we are urged to swallow: Homer does not paint landscapes; he does not paint figures in harmony with landscapes or represented by landscapes. He paints individuals surrounded by forces, either natural or social, that are antagonistic and intractable. Homer, like Manet, had experienced civil war first hand; even more than Manet his work is dominated by a sense of powerlessness. His protagonists (Black, White Male, Female, Human, Animal are surrounded as we are by forces against which they must struggle with little understanding. Neither do we understand them, these forces. But we must struggle to understand them all the same.

Robert Darnton, “Journalism: All the News That Fits We Print,” The Kiss of Lamourette. Reflections in Cultural History (New York: W. W. Norton, 1990), 60-93.

Roberta Smith, “Winslow Homer: Radical Impressionist,” New York Times, April 7, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/07/arts/design/winslow-homer-painter-metropolitan-museum.html

Winslow Homer, Scarborough, Maine, letter to M. Knoedler & Co., New York, NY, February 19, 1902; quoted in Stephanie L. Herdrich, “Crosscurents: Conflict, Nature, and Mortality in Winslow Homer's Art,” Winslow Homer. Crosscurrents. Exhibition catalog with entries by Daniel Immerwahr, Christopher Riopelle, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, Winslow Homer, Stephanie L Herdrich and Sylvia Yount (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, N.Y; National Gallery, Great Britain: 2022), 143. The original is at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

ibid.

Henry James, “On some pictures lately exhibited;” The complete writings of Henry James on art and drama, edited by Peter Collister (Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press, 2016), 118, 113, 117.

Henry James, “Parisian Festivity,” The complete writings of Henry James on art and drama, 177-78. First printed in the New York Tribune, 13 May 1876.

Henry James, The American Scene (London: Chapman and Hall, 1907), 46, 44, 46.

James, “On some pictures lately exhibited,” 113, 117.

Paul Werner, "Masters of Repressionism," WOID. A journal of visual language (Vol XX, no. 41; March 1st, 2013). http://theorangepress.com/woid/woid20/woidxx41.html

Claude Digeon, La crise allemande de la pensée française, 1870-1914 (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1992), 35, 37. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb366558220

Michiko Kakutani, The Death of Truth. Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump (New York: Crown Publishing, 2018), 5, 56 sqq.

“Sale of Pictures,” The Evening Post (Thursday, April 19, 1866), p. 3, column 7; quoted in H. Wood, Near Andersonville. Winslow Homer's Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 29.

George Heard Hamilton, Manet and his Critics (New Haven : Yale University Press, 1954), 45, 120.

Henry James, "The Letters of Eugène Delacroix," The complete writings of Henry James on art and drama, 321.

Christophe Charle, « Opus infinitum », in Pierre Bourdieu, Manet: Une révolution symbolique (Paris: Éditions Raisons d’Agir/Seuil, 2013), 543.

Meyer Schapiro, “Courbet and Popular Imagery: An Essay on Realism and Naïveté,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes Vol. 4, No. 3/4 (Apr., 1941 - Jul., 1942): 164-191.

A note in passing: Edward Bellamy, the late nineteenth-century utopian Socialist writer, wrote a short story in which people had become empowered to communicate "pictures of the total mental state," as opposed to "imperfect descriptions of single thoughts." Perhaps total mental states were a nineteenth-century thing. --- PW