“[Morphology] presents us with innumerable and infinitely varied forms that are nevertheless related by an unmistakable family likeness. For us they are representations that in this way remain strange to us, and, when considered merely in this way, they stand before us like hieroglyphics that are not understood.”

„Diese letztere führt uns unzählige, unendlich mannigfaltige und doch durch eine unverkennbare Familienähnlichkeit verwandte Gestalten vor, für uns Vorstellungen, die auf diesem Wege uns ewig fremd bleiben und, wenn bloß so betrachtet, gleich unverstandenen Hieroglyphen vor uns stehen.“

Arthur Schopenhauer, Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, II, §17.

Once, eons ago, I took a course on reading Maya inscriptions. Week after week we’d examine drawings from monuments and stelae, and classify glyphs. A glyph composed of a shield nestled into a snarling jaguar’s head meant “Shield Jaguar,” a ruler’s name. A hand grasping a fish was a “capture glyph.” Put the two together and it meant Shield Jaguar captured somebody. Or maybe Shield Jaguar went fishing with his bare hands. Fish-in-Hand, we were told, was an “event glyph” equivalent, roughly, to a verb or adverb because it was associated with a date, and Maya dating systems were the only part of the Maya writing system people thought they understood.

It didn’t stop there because the symbols used for dating were also used for something else entirely. The symbol for ahaw, “day,” or “for starters” could also mean and sometimes meant ahaw, “Ruler.” Primo might have been the best translation.

“Think of the tools in a tool-box: there is a hammer, pliers, a saw, a screw-driver, a rule, a glue-pot, nails and screws.—The functions of words are as diverse as the functions of these objects.”

„Denk an die Werkzeuge in einem Werkzeugkasten: es ist da ein Hammer, eine Zange, eine Säge, ein Schraubenzieher, ein Maßstab, ein Leimtopf, Leim, Nägel und Schrauben.—So verschieden die Funktionen dieser Gegenstände, so verschieden sind die Funktionen der Wörter.“1

Wittgenstein’s comparison goes far: just as you can use a drill bit to clean your teeth, so, too, you might (were you a Maya) use a totally different glyph to name a date, or honor a ruler. As with Chinese characters most glyphs were compounds of qualifiers: affix, subfix, postfix. Except, there seemed to be no logical subordination of one to the other. A qualifier might, at any time, become the qualified; and there seemed to be no consistency in the use or function of the parts or whole.2 One glyph commonly used to designate a ruler happened as well to be the sign for “vulture,” compounded of the glyphs for “shit” and “head.”3 I always liked those Maya.

The classificatory approach we used in class struck me, and strikes me still, as beside the point. Artificial Intelligence wasn’t a thing back then, but if we’d fed those descriptions into one of those image-generation sites the answers would have been consistently incoherent, like a roll of the semantic dice, not only for lack of understanding of each glyph but for lack of understanding of the process by which we could determine the relation between parts or, for that matter, the functions that connected the parts themselves, as well as the imputed connection of the whole to the life it purported to represent:

The problem with AI generated art isn’t that it’s art; it’s that it’s bad art, that’s why it wins prizes. The problem with Maya glyphs is, they’re a difficult, a challenging artistic process. I always liked those Maya.

In a searing critique of the classificatory approach, Claude Lévi-Strauss argued that you get nowhere by distinguishing types of images, or types of behavior, or types of any type, including types of type or script. Instead one needs to focus on the role of each in its particular setting. Glyphs and images and the stereotypical characters in a Russian fairy-tale play pretty much for Lévi-Strauss the role that day residue plays in dreams in psychoanalysis: don't look for what it seems to represent, just look at what it’s doing. A picture of a jaguar might mean “jaguar;” or it might merely sound like the Maya word for “jaguar” and have a different function in a different context, or several divergent functions and contexts at once. It might not be about a jaguar but about what jaguars do, the same way a hand grasping a fish is not about the fish but the grasping: not the object represented but the activity that's assigned to the object.

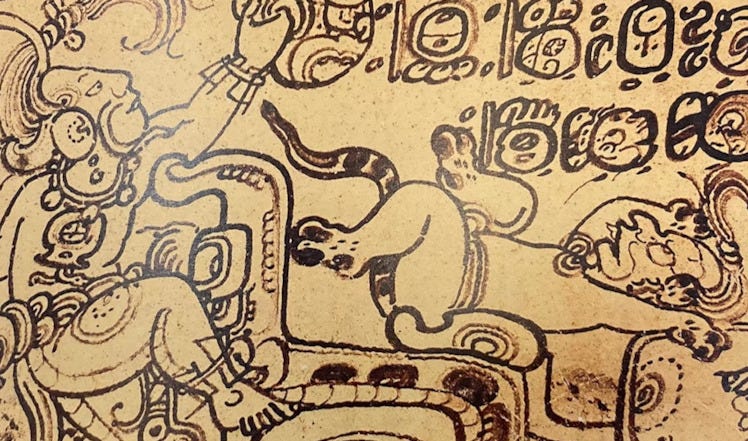

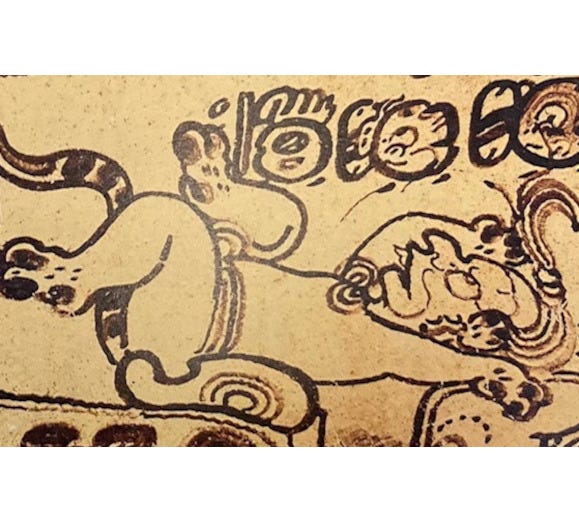

Take the mythological scene on the side of a small vessel that’s on display in Lives of the Gods:4

At the center of this section of the vessel (except there is no center) lies Baby Jaguar awaiting sacrifice, not too concerned about it, babies are like that. A god hovers over him with a sacrificial knife. Easy to tell a jaguar, but why “baby?” Here's why:

This is what is called semasiographic writing: it has nothing to do with sounds or syllables, it merely points the viewer to a social experience, an experience that as a rule in Maya art is not subordinate to a written narrative. The script across the top is not subordinate to the images, it's an incantation that appears in other contexts on other objects. The script does not explain the image and the image does not correspond to the narrative presented by the script, together they constitute the socially determined meeting of a script and a jaguar on a sacrificial altar. Nor is either subordinate to the other, textually or formally: so much for the "rigidly vertical" organization of Maya society and culture.

No one did more to dispel the myths of a hierarchy of signifying systems in Maya visual culture than Michael D. Coe. In Breaking the Maya Code, Coe laid out the history of the vast miscomprehension that delayed the reading of Maya writing until the 1970s, starting in 1563 when a Spanish priest named Diego de Landa was ordered back to Spain for unauthorized persecution of the indigenous people of Yucatan:

“We found among them a large number of books in these their letters, and because they had nothing in which there was not superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all.”

Landa tried to deflect his guilt by parading his insider knowledge of Maya writing: of how he'd worked with a Maya scribe to demonstrate the Maya had an alphabet just like ours, except for the devil part: “Of their letters I will give here an A, B, C.”5 Except, there was no ABC in the sense of a simple phonetic system, let alone a one-on-one match of sign to sound. The idea made no sense to Landa’s Maya informant, who gave up in disgust. Landa's error lay in the model imposed on all writing systems by linguists who insisted on placing a the European phonetic script at the top of an evolutionary chain. Referring to Ignace Gelb, author of the foundational text A Study of Writing. The Foundations of Grammatology, Coe states:

“I cannot really call him a racist. His book, however, is very definitely infected with that sinister virus of our century. It appears to have been inconceivable to him that a non-White people could ever have invented on their own any kind of script with phonetic content.”6

Yet Coe’s own internalized hegemonism seeps through: he does not question the idea that phonetic writing systems are the model for what writing is, the teleological vanishing point toward which all systems evolve: “There is no such thing as a purely pictographic writing system” [p. 25]. Compare this statement with Jacques Derrida’s own assessment in De La Grammatologie, his classical critique of Logocentrism whose very title is borrowed from Gelb: “For the essence of the sign is, to not be an image.” (« Car le propre du signe, c'est de n'etre pas l'image » ). Or with Roland Barthes: “Letterforms are precisely that which resembles nothing.” (« La lettre est précisément ce qui ne ressemble a rien »).7 Likewise, when Coe conjectures the origins of the Maya writing system he tentatively rejects a likely visual precedent, the so-called danzantes: carved stone slabs of the Zapotec culture at Monte Albán, in Oaxaca, Mexico:

For Coe and others, semasiographic images, images that convey meaning by visual parallels rather than by correspondence to spoken sounds, occupy the lowest rung of writing, if that: “I doubt that [the Zapotec writing system] ever achieved the completeness of Maya writing” [pp. 63-64].

This is throwing out the jaguar with the bathwater. To insist that the criterion for a “true” writing system is its completeness, is to exclude from consideration those signs that must remain incomplete because they require for completion a knowledge of social practices external to the signifying system itself. Maya culture, with its emphasis on recurrence, was not one to toss out seemingly archaic or vestigial systems, any more than poets are likely to toss out archaisms: the Maya writing system itself is a form of poetry-making, and there are few Maya writings that could be considered the equivalent of a laundry list, or a warehouse count.

Back in the classroom, as we sweated over glyphs, skilled young Mayanologists were turning up at scholarly conferences, listening politely to lectures about morphology, then retiring to the library to sit on the floor and pass a joint and run through all the permutations, trying to figure out, not what a glyph means, but the process of its meaning. Could a glyph be played backwards like Louie, Louie? And why was Son-of-Cart-Knee shown barefoot? They were closer to the Maya experience than anyone could hope to be, considering that the Maya, too, were up to smoking anything at hand. (Bananas weren’t available.)

A minor breakthrough occurred when a group gathered in the ruins of Palenque was discussing the Snake Jaguar glyph and one among them wokingly suggested that instead of “Snake Jaguar” one particular lord should be called Chan-Bahlum, the pronunciation for “Snake Jaguar” in Chol, the local Mayan language. [Coe, p. 205.] As things turned out, the ruler’s name was pronounced Can-Balam, the Yucatec Mayan version—which in turn raises all kinds of interesting questions: did the rulers of Palenque speak a different form of Mayan than their subjects, like English toffs ? One had to approach these glyphs, not as isolated object of perception, but as active subjects in a dialectical relation to other forms of experience, of which spoken language was only the most obvious—in other terms, a totality. To read the glyph you first must be the glyph.

I experienced this a number of years ago, in the ruins of Coba [Ko’ba a], Quintana Roo. I’d been trying to read inscriptions with the help of a book by Linda Schele, the most brilliant of the brilliant youngsters. I was puzzled by a glyph described as a “crocodile’s foot:”

It was a crocodile’s leg, so what? The next day, as I was walking along the road that bordered the lagoon, I noticed a group of men in sombreros surrounding what appeared to be a sleeping crocodile. Then it shifted, ever so slightly, on its legs, and they were gone. To anticipate the unfolding of the crocodile vision you must know every potential gesture of the crocodile as it unfolds. Don't look for what it seems to represent, just look at what it’s doing.

You wave the first word. And the whole thing follows. But You follow it. With a dog at your heels, a crocodile about to eat you at the end, and you with your pack on your back trying to catch a butterfly.

Charles Olson, American poet.8

WOID XXIII-05b

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations [Philosophische Untersuchungen], Teil I, 11. (London: Blackwell Publishing, 1953), pp. 7 & 6.

Michael D. Coe and Justin Kerr, The Art of the Maya Scribe (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), pp. 50-51, 154.

Linda Schele and Mary Ellen Miller, The Blood of Kings. Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art (New York: George Braziller, 1986), pp. 325-26.

Schele and Miller, pp. 287, 298-99.

Michael D. Coe, Breaking the Maya Code (New York : Thames and Hudson, 1992), p. 104.

Breaking the Maya Code, p. 26. Ignace J. Gelb. A Study of Writing. The Foundations of Grammatology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952.

Jacques Derrida, De la Grammatologie (Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1967), p. 67; mistranslated as “For the property of the sign is not to be an image” in Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans and preface by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), p. 45; Roland Barthes, “Variations sur l'écriture,” Oeuvres complètes, Vol. III, ed. Eric Marty (Paris : Seuil, 1993), p. 1449.

Charles Olson, “A Foot Is to Kick With,” Collected Prose, ed. Donald Allen and Benjamin Friedlander, with an introduction by Robert Creeley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), p. 269.