Review : Vittore Carpaccio. Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice. November 20, 2022 through February 12, 2023 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; March 18 through June 18, 2023 at the Palazzo Ducale, Venice.

Catalog: Peter Humfrey, Andrea Bellieni, Gretchen Hirschau et al.. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

Access : National Gallery of Art, West Wing. From Union Station (Washington) take the Circulator Bus directly outside the station and to your left in the direction of the National Mall. Fare is $1.00, payable in cash.

I]

Michelangelo:

“ In Flanders they paint with a view to external exactness of such things as may cheer you and of which you cannot speak ill, as for example saints and prophets. They paint stuffs and masonry, the green grass of the fields, the shadows of trees, and rivers and bridges, which they call landscapes, with many figures on this side and many figures on that. And all this, though it pleases some persons, is done without reason or art, without symmetry or proportion, without skillful choice or boldness, and, finally, without substance or vigor.”1

Would Carpaccio have fit the description? What’s certain, is that he appeals to those reviewers and readers who think paintings “tell a story,” that the painter’s done when he’s told the story, and the critic’s job is to tell the story told, “such things as may cheer you and of which you cannot speak ill:”

Ooooh! Goggie!

Carpaccio was at the height of his career in1502, the year he painted the doggie and Michelangelo carved the David and it’s good to be reminded because there’s something Medieval about him—regressive, if you will—that deserves thought. Amateurs love to compare Carpaccio’s Saint George and the Dragon of 1502-08 with Paolo Uccello’s Battle of San Romano painted roughly 50 years earlier, but there are differences that have less to do with the objects depicted than how they’re arranged across the surface of the painting:

In good Renaissance fashion Uccello designs his image (a corpse) to fit within the orthogonals, then fits it within the orthogonals along with other elements to reinforce the orthogonals, the broken lance for instance. Carpaccio pits his figure against other elements that conflict with the concept of single-point perspective: the frog aligned along another orthogonal whose vanishing point lies below the vanishing point for the cadaver, in the style of Flemish painters; the horse’s skull, parallel to the picture plane; and the body of water beyond that’s of another world, resolutely flat. Uccello wants to do single-point perspective but he can’t quite get it right. Carpaccio can, but he doesn’t want to, he’s approaching the process from another point of view.

II]

Some time before 1399, Cennino Cennini wrote,

"If you want to acquire a good style for mountains, and to have them look natural, get some large stones, rugged, and not cleaned up; and copy them from nature, applying the lights and the dark as your system requires."2

A mountain’s just a rock, only positioned to look bigger. What Cennini’s system requires — the organizing principle of the finished painting — is a single, consistent source of light that unifies all elements, which is what you’d expect of a student of Giotto’s son-in-law. Instead, Carpaccio lays out the elements of his composition in a two-dimensional abstract pattern, interlocking planes held together by consistent use of one or two dominant colors, a “color key.” The rock returns to its original function.

For John Ruskin, who rediscovered Carpaccio in the nineteenth century, there was no tension between the flat, interlocking set of patterns and the “story” because Ruskin had little or no depth perception. Michelangelo saw things otherwise:

I do not speak so ill of Flemish painting because it is all bad but because it attempts to do so many things well (each one of which would suffice for greatness) that it does none well.

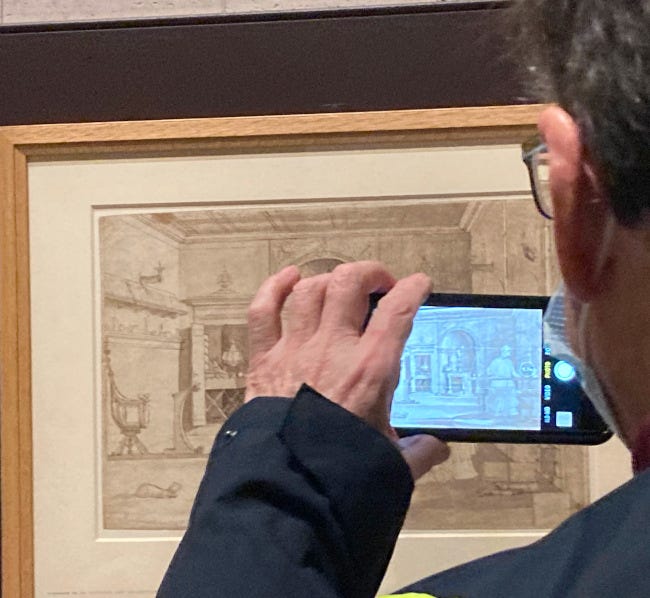

To which he added that Italian artists, even when they followed the same style as the Flemings, were apt to do better because their environment was more supportive; Vasari, Michelangelo's groupie and therefore the first art historian, says something similar in his chapter on Carpaccio.3 And Michelangelo was right: There is one area where Carpaccio gets close to greatness because he's leaning on centuries of studio practice: his drawings. Almost half the hundred-odd artworks in this show are drawings, and they're the show's best feature, its most original contribution, and its most popular attraction:

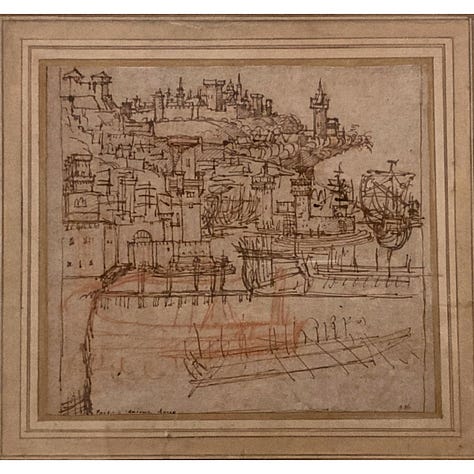

The most puzzling as well: Drawing as a practice grows out of the Medieval tradition of pattern-books, collections of ready-made images, the workshop’s stock-in-trade because they could be used and used again for any new commission: the angel, the rock, the dog. But there are no dogs or angels in Carpaccio’s drawings, at least in this show. Carpaccio’s drawings do not depict the parts but the relations of parts, and this makes them autonomous works of art:

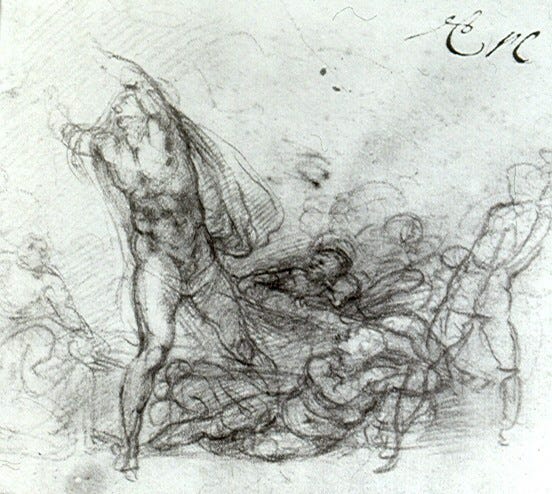

Each of these solves a single problem; does one thing, and does it very well, like the play of modulated mass against blank space, which would have delighted Michelangelo:

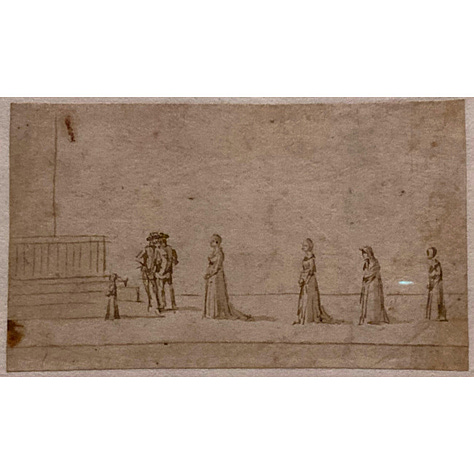

Or the play of mass against the edges, which raises the persistent problem of Disegno. “Disegno” in Italian means both “Drawing” and “Intention,” but the intention behind a drawing can never be taken for granted. The exhibition too easily suggests that the design (intention) behind each design (drawing) is a finished painting, which is not borne out by the works themselves. The brief overview of Carpaccio’s drawings in the catalogue is not much help.4

By 1500 drawings were beginning to be understood as valuable in their own right; Vasari himself collected them. To read the “play of form against the edges” is to assume the trimming of the drawings was part of Carpaccio’s original intention because it’s consistent with his own fascination with balance; on the other hand a number of sheets have drawings on both sides, so it’s possible the drawings were trimmed in Carpaccio’s time, perhaps by Carpaccio himself, but that the trimming was not his original intention. Perhaps, as his reputation fell, he turned to drawings as a means to earn a living, and trimmed existing sketches; or perhaps he made sketches out of earlier designs, after the paintings they might be believed — erroneously — to anticipate.

Too challenging, Jason? Have another doggie.

WOID XXIII-03

Francisco de Hollanda, Four Dialogues [1548]; quoted in Italian Art, 1500-1600: Sources and Documents, ed. Robert Klein and Henri Zerner (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 200) p. 34.

Cennino d'Andrea Cennini, The Craftsman's Handbook “Il Libro dell' Arte,” transl. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. (New York: Dover Publications, 1960), p. 57.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, translated by Gaston du C. de Vere; (New York: Random House, 1996), Vol. I, pp. 597-98.

Catherine Whistler, “Carpaccio as Draftsman,” in Vittore Carpaccio. Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice, ed. Peter Humfrey (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022), pp. 59-74.