Characters count

WOID XXII-43

“Will not captions become the essential component of pictures?” Walter Benjamin.

Anarchist. Wit. Man of exquisite taste in Art and Fashion. What’s not to like? Also, art critic. Félix Fénéon was among the first to discover Seurat, Rimbaud and Lautréamont. And from 1906 on he authored faits divers for a French tabloid: twitter-length synopses of the lurid, the petty and the familial, sometimes all in one:

« Dans un café, rue Fontaine, Vautour, Lenoir et Atanis ont, à propos de leurs femmes absentes, échangé quelques balles. »

“In a café, rue Fontaine, Vulture, Lenoir and Atanis traded a few bullets respecting their absent wives.” [Character count: 105.]

« Muni d’une queue de rat et illusoirement chargé de grès fin, un cylindre de fer-blanc a été trouvé rue de l’Ouest. »1

“Endowed with a rat’s tail and deceptively loaded with fine sandstone, a tin cylinder was found rue de l’Ouest.” [Character count: 113.]

Just like Twitter, the format constrained Fénéon. Like his friend Mallarmé Fénéon embraced these constraints, they determined the lapidary elegance of his style.

Fénéon’s faits divers are the other side of his restrained yet empathic art criticism, defined, like faits-divers, by absence: one is reminded of Walter Benjamin’s take on Eugene Atget’s photographs of empty streets, “not lonely but voiceless,” images that demanded interpretation, “opening the field for politically educated sight.”2 Fénéon’s style, like Mallarmé’s or Baudelaire, defined itself through the implication of absent views and narratives, albeit from its own, uniquely materialist angle, quite different from Baudelaire or Mallarmé’s:

« Ces mers, vues d’un regard qui tombe perpendiculairement, couvrent tout le rectangle du cadre ; mais le ciel, pour invisible, se devine : tout son changeant émoi se trahit en inquiets jeux de lumière sur l’eau. »3

“Those seas, seen from a glance that falls at a perpendicular, cover the whole rectangle of the frame; but the sky, though invisible, may be guessed: its shifting emotion, all, betrays itself in an anxious play of light upon the water.” [Character count: 222.]

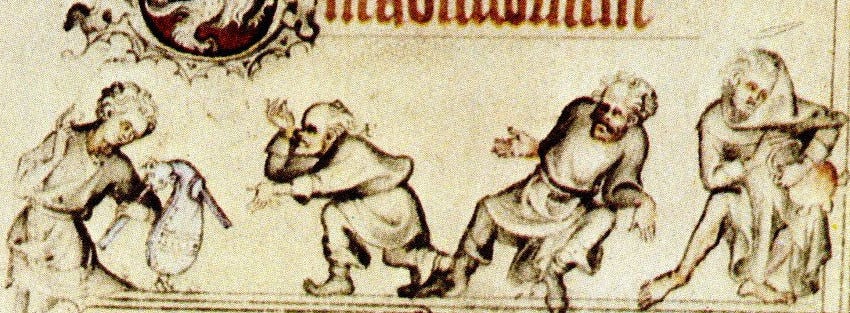

As with Marx so with Fénéon: consciousness was to be determined by historical and social circumstance. The task of the critic was to bring readers and viewers to a consciousness of their own shifting consciousness, much as viewers of Monet’s Nymphéas find themselves placed in a shifting relationship to the canvas, or as Benjamin expected of Surrealism; much as Fénéon, in his anarchist criticism, hoped of his proletarian readers, like the tension of an unseen sky reflected on shifting waters. In his relationship to the image or the narrative Fénéon took on the role of the Dichter, the one who condenses the visual text to its contextual sense. “Dichter,” the German noun for “poet,” is commonly glossed as a pun on the adjective dicht, for “condensed.” In fact the word Dichter derives from the Late Latin dictor, “the one who speaks.”4 The poet’s role was / is to appose the full authority of language against the passive act of presentation; to re-present that which the text (visual or verbal) cannot or will not say. There are parallels, useful parallels, to be found in the images in the margins of Gothic manuscripts, even more so in the Gothic bas-de-page whose format is similar to today’s online headers, strips of narrative “where the future is nesting, even today, so eloquently that we looking back can discover it.”5

"If the narrative... depicts how the Word was made Flesh, this is reversed in the anti-incarnations of the edge, which are worldly, fragmentary and fleshly."6

Not to mention witty, controlled and disruptive. The Flesh made Word: now that’s a task to get behind.

October 8, 2022

Félix Fénéon, Œuvres. Introduction de Jean Paulhan (Paris : Gallimard, 1948), pp. 318, 308.

Walter Benjamin, "Walter Benjamin's 'Short History of Photography'" [Die kleine Geschichte der Fotographie, 1931], trans. Phil Patton. Artforum Vol. 15, no. 6 (February 1977).

Fénéon, Œuvres, p. 28.

Augustine, De Doctrina Christiana 4, 10, 25.

Benjamin, op. cit.

Michael Camille, Image on the Edge. The Margins of Medieval Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 50.