Samuel Moyn. Liberalism Against Itself: Cold War Intellectuals and the Making of Our Times. Yale University Press, 2023

“Though a debate is more dignified, it suffers in this case from the distortion of presenting a grave contest of two personified ideas where in actuality there exists only the act of a single clown who keeps losing his trousers.” - Harold Rosenberg on Cold War intellectuals

A friend, when she was young, was on a train in Italy. She found a seat in a compartment with three young men. The boys hadn’t planned to share, but here was a ragazza! Then an old lady came on, a nona, so… Then a nun, so of course. The conversation turned to Our Lady of Loreto. Was the signorina going to Loreto, too? No, she said, I’m Jewish. Embarrassed silence, then from the nona: “The Jews killed Christ!” Awkward silence. “But, no,” said the nun, kindly. Again the nona: : « È la verità! » The nun, with all the calm authority at her command: « Ma ci sono due verità! » There are two forms of truth.

This is the skill we need in order to negotiate between the lived necessities of life in society and the fantastic ideological standards that weigh us down, “like a gigantic insect,” Marx would say — or was it Kafka? On one side the daily, the minute, the grain of social life; on the other the abstract, idealized world of theory that pushes down, in what Freud calls die Einschüchterung der Intelligenz, the gagging of the intelligence.1 Two truths; one to theorize, another for getting along with others. No different from the double ideological lives lived by ordinary Russians in the last days of the USSR. No different from our ordinary American lives today.

John Dewey opens his 1915 smackdown of German Philosophy and Politics with a similar caution:

“When we note that Marx gave it away that his materialistic interpretation of history was but the Hegelian idealistic dialectic turned upside down, we may grow wary. Is it, after all, history we are dealing with or another philosophy of history?”

Dewey was not primarily addressing Marx (or even a particular type of Marxism), but a misinterpretation of the social function of interpretation that was widely shared at the time and still is. According to Dewey, philosophies of History, unlike historical events, were reflective, not determinant,

“Not a genuine discovery of the practical influence of ideas. In other words… the esthetic type, even when sadly lacking in esthetic form.”2

“Aesthetic,” to Dewey, means the whole of human immaterial exchange, the sensual and the intellectual within a socially determined environment. This was not to say that political theorizing, or theoretical propositions, had no influence in changing the course of affairs, but that theorizing itself should be understood, first and foremost, as a social (“aesthetic”) performance, intellectual merchandise in the marketplace of ideas. To pretend otherwise was to conspire with the reader about the social function of theorizing itself, the real purpose behind Samuel Moyn’s book. As Marx pointed out in the Third of the Feuerbach Theses,

“Materialist [i.e., mechanistic] theories of change through circumstance and education [Erziehung] ignore the fact that circumstances are changed by men, and the educator, too, needs to be educated. Because of this these practices must divide society into two parts, one of which they exalt over the other.”

„Die materialistische Lehre von der Veränderung der Umstände und der Erziehung vergißt, daß die Umstände von den Menschen verändert und der Erzieher selbst erzogen werden muß. Sie muß daher die Gesellschaft in zwei Teile - von denen der eine über ihr erhaben ist—sondieren.“3

Which Michael Harrington elegantly parses:

“Whenever the subjective element, the creative role of consciousness — the function of self-changing — is taken out of socialist theory and it becomes deterministic, then the ideological foundations are laid for one part of society raising itself above the other.”4

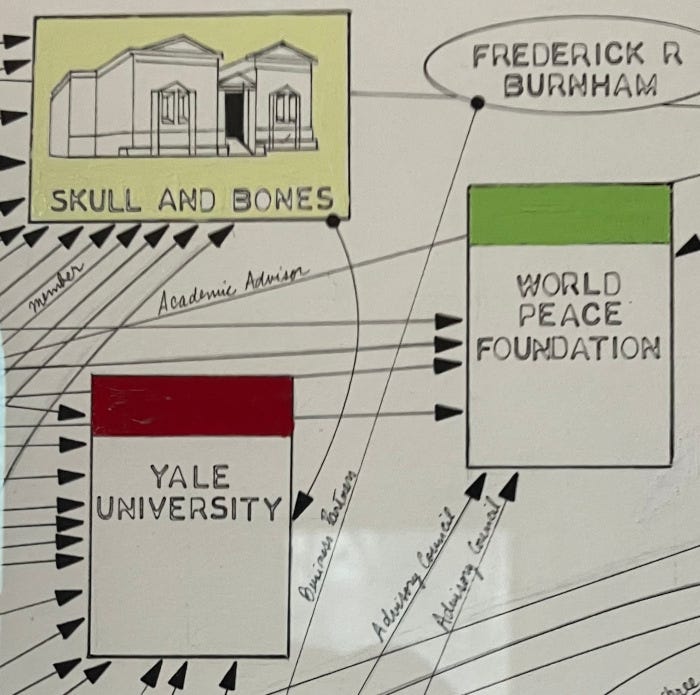

Raising one part of society above the other is not incidental to Moyn’s activities as a a writer and teacher, it’s their primary function. Moyn teaches Law and History at Yale, an institution not renowned for drawing the distinction between what each individual thinks they’re thinking and whatever leverage they may think their thinking has on History. The whole point of an elite university is to blur this distinction; to make the reader or student think their thinking will have consequences for Society. This is the attitude that unites Moyn with the subjects of the book under review, far more than it separates him.

Cold War Liberalism, writes Moyn, was a deflection of the true purpose of Liberalism which, according to Moyn, is notable for its questioning of Zionism and colonialism, its commitment to gender and racial equality, its love for something called “Democracy.” Instead, Cold War liberals spent their capital in a moralizing, defensive posture against change. To argue his case Moyn brings up five chosen exemplars of Cold War Liberalism: Judith Shklar, Isaiah Berlin, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Karl Popper and Lionel Trilling, as if these five had ever presented a consistent intellectual front. It’s fun to watch Moyn tear them apart, one by one, though the tearing has little to do with his thesis. There’s a lot of footnote-dropping, too, but not much substance behind that, either. The problems lie elsewhere.

For instance, Moyn approaches the literary critic Lionel Trilling from the viewpoint of his changing attitude to Sigmund Freud. Trilling, in his early Marxist wannabe days in the ‘Thirties, had denounced Freud as an intolerable bourgeois pessimist. After turning bourgeois pessimist himself he praised Freud for being the very tolerable bourgeois pessimist he’d fantasized at the outset—a projection that has nothing at all to do with Freud, but contributes mightily to the campus Freud industry. There’s also a series of score-settling swipes on Moyn’s part, directed at Peter Gay, who has nothing to with the matter at hand, unless it’s the fact that Gay wrote about the Enlightenment, which Moyn seems to consider his private intellectual preserve.5 In the end these chapters boil down to little more than a settling of scores and faculty whispering campaigns, both of which are far preferable to the Introduction and the Epilogue, where the serious thinking pretends to take place.

In the end, though, Cold War Liberalism may be different in content from Moyn’s New! Improved! own brand. It’s no different in function. Moyn writes with all of the hand-over-heart sincerity of an insurance CEO announcing that from now on the Company’s returning to its true mission. It does not occur to him that the failures of Liberalism, Cold War or other, are not a bug, they’re a feature. Dewey again:

“I believe it is easy to exaggerate the practical influence of even the more vital and genuine ideas of which I am about to speak.”6

Those are Moyn’s exaggerations as well. Did Hannah Arendt have any influence on public policy? Did Isaiah Berlin? Or Himmelfarb? As for Trilling: could anyone imagine that Trilling’s fantasies of Freud as a “moralist,” and littérateur have any reality beyond their function, which is the repression and denial of the role of Psychoanalysis as social healing? Moyn passes this all under silence though, to give him credit, there’s a single footnote somewhere referencing Richard Titmuss, the influential British architect of progressive social policy in the ‘sixties; one gets the impression that the very concept of public policy is as foreign to him as it was to Himmelfarb, Arendt, etc. For Moyn, as for Arendt et les autres, progressive social policy is not an option; only progressive tongue-wag.

If I’ve reached back to Dewey and Rosenberg, it’s because both were dealing with similar historic conjunctures, perhaps similar to our own as well. Writing at the outset of World War One, Dewey asked how German Idealistic Philosophy could have furnished a rationale for German militarism. Philosophy, he argued was neither cause nor motivation, merely the means to establish the discursive conditions by which War had been normalized in German culture. Likewise, Harold Rosenberg, writing in 1957, was not fooled by the pretense of an intellectual struggle between the Cold Warriors represented by Trilling and others, and whatever version of a claim to political commitment had preceded or might follow. Rosenberg, no doubt, would fail today to be impressed by Moyn’s staged matchup between Cold War Liberalism and the Liberalism of the Future as imagined by Moyn himself. The problem isn’t the type of Liberalism, but the underlying, unchanging protocols and processes of Liberalism as it’s practiced—or rather, theorized as practice.

Moyn wants us to believe he’s advocating for change; what he’s advocating is advocacy for change; which places him squarely in the tradition of eighteenth century political thought,

“claiming that virtue might be reaffirmed independently of social conditions and might even change them.”7

Beginning in the Cold War Era, the ancient “Macchiavellian” theory of social relations in a democracy was codified as the dominant socio-political narrative, notably in the writings of the Talcott Parsons, the dominant American sociologist. The only difference is, that “Virtue” is now called “Values,” and the values are always the dominant values that the dominant class hopes to find among the dominated, only to whine when they can’t be found.

A history of the collapse of the Narrative of Values might be traced to President Eisenhower’s call in the late ‘fifties to enforce the values enshrined in the Constitution, values which in fact had only just been affirmed by the Supreme Court. This was coupled with the belief that enforcing these values was a mere matter of enforcing formal, legal rights: right to vote, right to equal opportunity, etc. It soon became evident, at least among those of us who wanted change, that advocating for America to stand up for the values it claimed to incarnate was a poor substitute for putting those values into practice. Today, that same resentful contesting of legitimacy that had first overtaken the Left, has become general. The “Values” approach still drives consultants and pollsters for the Democratic Party; but a majority of American voters have long given up on it. Moyn is not so sure: one of the few heroes in his book is Arthur Schlesinger Jr., a liberal of the Kennedy era of whom Moyn writes, that his ideas

“..were flexible enough to evolve from the ambiance of Cold War liberalism in the late 1940s and early 1950s toward the more ambitious and aggressive version of the 1960s.”8

I once shared an elevator with Schlesinger, following a seminar at the very multicultural, multinational Graduate Center at CUNY, in New York. It was long, quiet ride.

If only Liberals had thought a bit better, Moyn suggests, the problem would have been solved. But the Civil Rights movement of the ‘sixties didn’t collapse because the right footnotes weren’t in the right place; it collapsed because “ambitious and aggressive” folks like Schlesinger were perfectly content to talk the talk of Democracy, they couldn’t be bothered to shoulder the burden of implementing their promises, except for placing responsibility on those to whom the promises had been made. Today, I suspect, the same could be said of the Democratic Party as a whole. It could be said, perhaps in equal measures, of Moyn and of the warriors he critiques.

Because the point of Liberalism, at least the way Moyn describes it, is to not implement its promises. This is the Deutsche Bahn system: the belief that thinking about solving a problem is the equivalent of solving it, and beyond, the belief that you’ve solved the problem simply by acknowledging its existence. Two truths: one for our daily consumption, the other as the official coinage. That ship has long sailed:

“A gospel of duty separated from empirical purposes and results tends to gag intelligence. It substitutes for the work of reason displayed in a wide and distributed survey of consequences in order to determine where duty lies an inner consciousness, empty of content, which clothes with the form of rationality the demands of existing social authorities.”

to which John Dewey adds:

“A consciousness which is not based upon and checked by consideration of actual results upon human welfare is none the less socially irresponsible because labeled Reason.”9

And Harold Rosenberg put it more pointedly for our purpose:

“The Cold War is not comparable to the Great Depression or World War II: it is not, like them, a physical reality accompanied by certain characteristic experiences and attitudes; from start to finish the Cold War is a struggle in the mental world, hence dominated by ideas which have reference not to hunger, fear, despair, but to influencing and coercing people.”10

To the American academic as to the American pollster, values are not something you follow, they’re something you trade in, something for coercing people. The reproduction and preservation of social distinctions demands the creation of many more Moyns at elite universities and in the positions of power for which those universities prepare them, ready in their turn to produce and reproduce a discourse without practical application to the world we live in, save intellectual coercion. We have met the enemy, and it is them.

WOID XXIV-27

December 22, 2024

Sigmund Freud, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur (Wien: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, 1930), p. 38.

John Dewey, German Philosophy and Politics (New York: H. Holt, 1915), pp. 6, 7.

Karl Marx, „Ad Feuerbach“ These 3. Manuscript, 1845; first published 1888.

Michael Harrington, The Twilight of Capitalism (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976), p. 48.

Moyn, “Mind the Enlightenment,” Review of Jonathan Israel, The Radical Enlightenment, (The Nation, May 31, 2010): https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/mind-enlightenment/ ; accessed December 12, 2024.

Dewey, op. cit., p. 6.

J. G. A. Pocock, The Machiavellian moment : Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (Princeton University Press, 2003, 1975), p. 459.

Moyn p. 170.

Dewey, German Philosophy, pp. 54, 54-55.

Harold Rosenberg, “Death in the Wilderness,” Midstream 3/3, Summer 1957; reprinted in The Tradition of the New (London: Thames and Hudson, 1962), p. 247