Dummy (1949-2024)

Remembering David Dumville

After decades of searching for Eternal Truth, a man ends up on the Highest Mountain, facing the Greatest Guru of them All. “Oh, Greatest Guru, what is the meaning of Life.” “Life, my child,” says the Guru with a smile, “is like a river.”

The man loses it: “Whaddaya mean? I searched and searched and climbed the highest mountain, only to be told that ‘Life is like a river!!!’”

The guru’s eyes pop out with excitement: “You mean… IT’S NOT!!!?”

David Dumville has died, to whom I owe an undying debt, who brought out my true self as a scholar; maybe an artist, too.

David was teaching a course in Paleography at the University of Pennsylvania, and the woman I lived with was struggling through her Master in Medieval English, and as she was required to take his course I asked if I could audit. “Sure,” said David, and could I be the first to present a collation to the class?

Collating a Medieval book, as readers of Lord Peter Wimsy know, means you analyze the book from every angle as a physical object, in order to understand it better. Can the ordering of pages, the size, the number of lines, point you to the scriptorium — writing studio — from which it came? Were the pages consistently ordered, or had several quires — assemblages of pages — from different scriptoria been assembled later? How were the holes made on each page, by which the lines were measured? How could one date the writing? How many scribes had worked on it? And finally: could this book and its texts be placed alongside similar texts to provide a clearer picture of the evolution of the text over time? To my partner and her grad student friends this was the most boring class in the world. To someone like myself, who was earning my living teaching and practicing calligraphy, it was a door to a new world.

Later, when after years researching, writing and teaching Medieval book techniques, I decided to go to graduate school, a wise old teacher told me,

“Watch it. You’re going to be sitting in the classroom thrilled by all this new knowledge and you’re going to want to talk about it; meanwhile, the teacher and students will be quietly hoping they can get through the hour without being found out for the frauds they think they are, and the person they’ll think is thinking it, is you.”

U-Penn’s English Department was full of that kind of faculty, interspersed with a handful of feminists with a drinking problem. The whole of British Academe, in fact, is nothing but, minus the feminists. The paleographers are even worse. If Dumville had been that kind of teacher he’d never have let me past the door. I never heard of him humiliating anyone.

My class assignment was, to collate a mess of a book, a collection of excerpts known as a Liber Scintillarum, “Book of Sparks,” a book made up of glints of purported theological wisdom, in other words a miscellany.1 This book was a mess: unidentified bits and pieces stuck together, near-illegible writing. Also, it appeared that someone had once dropped it in a privy, as one might determine by pointing out that the stain was from the top of certain pages down, and since Medieval books were, wisely, stored flat, the accident must have happened before the various pages had been assembled in their present state, which, judging from the elegant wooden boards that bound it, was previous to the sack of South German monasteries by Napoleonic troops. I concluded my presentation by quoting a thirteenth-century book of instructions from an abbot to his monks, reminding them, after a hearty dish of beans, to go outside in order to produce their scintillas. Dummy was impressed by my research skills in Medieval etymology and privies. He tactfully declined to share my conclusions.

What really got me started, though, was a lecture David organized at Penn, and the speaker was an eminent authority on Late Medieval Christian borrowings from Islamic thinkers, or something. She was close to eighty, French, and spoke ghastly English, and when David respectfully suggested she give her lecture in French instead, she barked him away from the lectern.

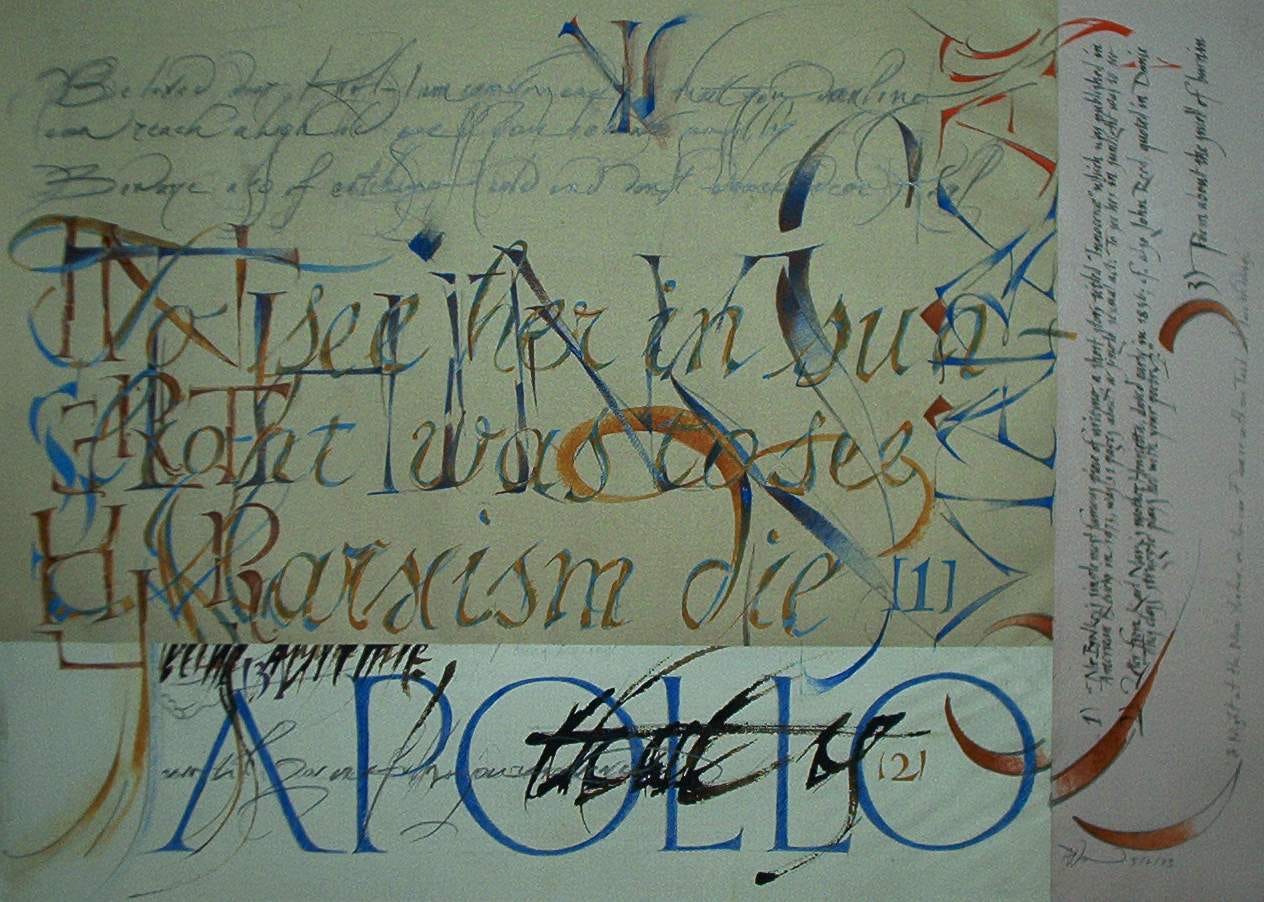

The rest was pure scintilla. On and on she rambled in an incomprehensible jargon. As my fellow-students fell into a stupor, I realized this was a secret language with its own alphabet, like those you find in Late Gothic manuscripts, say the ones in fake Arabic. I started furiously transcribing, aware, in the Medieval manner, that letters must have the shape of their own meaning, eternally obscure, mysterious. That was the beginnings of my first real painting. How could I ever thank the man? Oh, right.

WOID XXIV-26

December 2024

Manuscript 0609, University of Pennsylvania Rare Book Collection: Liber Scintillarum (Germany, late XIIIth-early XIVth century; https://archive.org/details/Ms.Codex0696_27 ; https://search.digital-scriptorium.org/catalog/DS1599