Pundit Brain: is that an oxymoron, or a tautology?

Mostly the latter. The expression has come up recently in discussions and recommendations about the proper strategies to be pursued by demonstrators against the Trump Regime. As a commentator once described it:

The main feature of Pundit Brain [is] The Normative-Descriptive Shuffle — which is a rhetorical trick used effectively by [New York Times pollster Nate] Silver […] Nothing is really worth fighting for on first principles, politicians should simply listen to the polls and adopt policies that reflect what is generally popular and uncontroversial. […] By prioritizing a description of the world, rather than attempts to change it, politics becomes a pseudoscience, a sport to be gamed rather than a mechanism for improving people’s lives.1

Not only politicians but demonstrators, who in the days leading up to yesterday’s massive demonstrations were encouraged, once again, to play the political strategist and behave in ways appropriate to “first principles,” meaning the correct and desirable outcome. When Timmie Snyder addressed the crowds in Philadelphia he wasn’t exactly planning to direct them toward their historic task in the Class Struggle.

Timmie stuns the Crowd.

In this way, Pundit Brain is dialectical: it opposes the pundit’s own thoughts to the imputed thoughts of the marching masses led by impractical hopes and fears.

In New York we call them kibitzers:

There must be some kind of rule, call it Pennies’ Law, that says the greater the crowd, the less likely it is to follow its self-appointed leaders, or pay attention. This past Saturday, the crowd was so densely packed at the intersection of 42nd and Fifth that the kibitzers couldn’t have moved the crowd if the crowd had been open to being moved to begin with. As yet another pundit put it, in a typical fit of normative description,

“We seem to have entered a new phase, in which the relationship between real-world protest and the debate stage of our phones has been somewhat inverted.”2

What you mean, “we,” pundit muthafugga?

Sigmund Freud knew a thing or two about the rationalistic claims of pundits and pseudoscientists. In the first pages of Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse [Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego], Freud set himself against the liberal-reactionary tradition—the punditry—that sees little more in mass activities than irrational behavior, meaning behavior without a goal that can be proven to be rational: Marching for Marching’s Sake. Early on, Freud had built his intellectual edifice on his own belief that the behavior of children, “primitives” and the mentally divergent had a logic all its own. In his later writings, written in sympathy with the Socialist era of Red Vienna, Freud was intent on providing a fourth leg to his argument: the behavior of the collective.3

Freud’s position blends with that of Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French anthropologist, who begins his own investigation of The Savage Mind by affirming the use-value of certain forms of “primitive” making and thinking, by means of

“a form of knowledge we would prefer to call ‘first’ instead of ‘primitive:’ one that is commonly referenced by the word bricolage.”

« une science que nous préférons appeler “première” plutôt que primitive : c'est celle communément désignée par le terme de bricolage. »

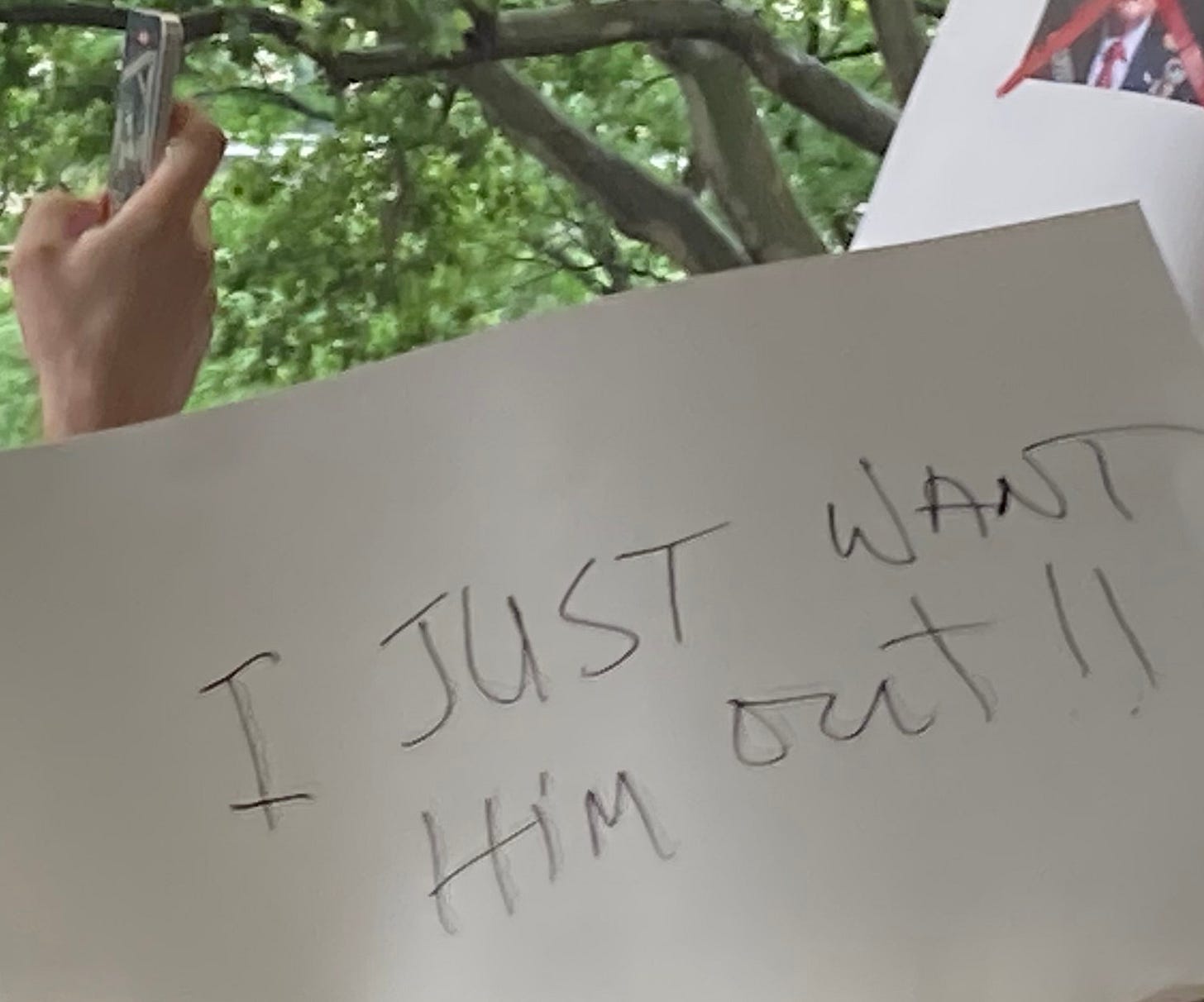

As your elementary school teacher might say, it looks as if you didn’t put much effort into this:

The first, notoriously incompetent English translation of The Savage Mind had some difficulty with the word “bricoleur,” a word that simply means a tinkerer:

“The bricoleur is still the one who works with his hands, [...] using means that are roundabout compared to those of the professional [literally, the man of Art].”

with the particular nuance that with Lévi-Strauss as with Freud, the bricoleur is one who tinkers with symbols and symbolic meanings as well as material objects; sometimes, as in the visual arts, the two together:

Mythical thought expresses itself through a repertoire that is heterogeneous in its composition and is, though extensive, still limited; yet thought must make use of this repertoire, whatever the task it sets itself, because it has nothing else at hand.”

« Le bricoleur reste celui qui œuvre de ses mains, […] en utilisant des moyens détournés par comparaison avec ceux de l'homme de l'art. Or, le propre de la pensée mythique est de s'exprimer à l'aide d'un répertoire dont la composition est hétéroclite et qui, bien qu'étendu, reste tout de même limité ; pourtant, il faut qu'elle s'en serve, quelle que soit la tâche qu'elle s'assigne, car elle n'a rien d'autre sous la main. »4

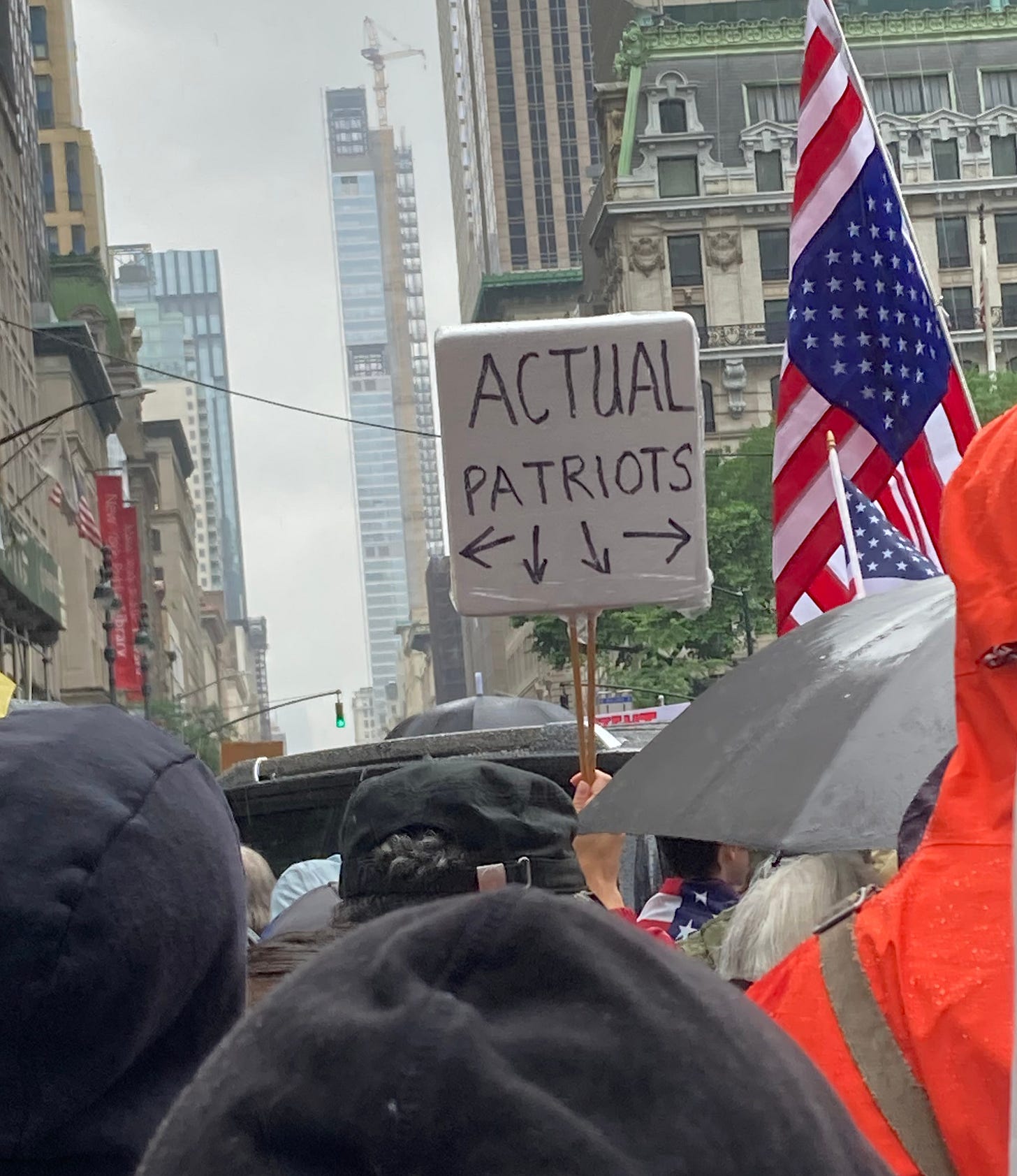

Hand or mind, the bricoleurs are those who proudly proclaim themselves to be playful amateurs:

Unlike the Men of Art:

The owner of this hat seemed thoroughly miserable; or maybe embarrassed?

As was the creator of this pistachio ice-cream cone:

Which, she explained, was meant to be a microphone; which, she thought, might mean a reference to freedom of speech. She wasn’t sure.

Both, the man with the Iwo-Jima hat and the woman with the ice-cream cone were struggling for something deviously meaningful, and not finding it. That something, that “nothing at hand,” as Lévi-Strauss calls it, is the pundit’s world of ends and means, the world of universal norms so eagerly proposed. The participants, for the most part, were having none of it.

Likewise, Freud and Lévi-Strauss have in common their rejection of the concept of a group mind, a world-soul, that Fascist fave, the concept of a Massentrieb, a herd instinct ripe for revelation or, for that matter, imputed consciousness in the Marxist manner. My colleague in Substack, James Crane, has provided a translation of an early, curious comment from Max Horkheimer of the Frankfurt School. It addresses, of all things, artistic representation, as opposed to artistic process:

“The impressionists in painting, on the other hand, and more so among the neo-impressionists in France […] render the image only in those necessary elements from which the desired effect of the whole would arise in the eyes of the beholder. […] All which was supposed to be the actual content of art is expelled from it, shoved into the eye, the attitude, the conception, or in any event the subject of the beholder—into his private sphere, so to speak.5”

On No King’s Day as well “those necessary elements from which the desired effect of the whole would arise in the eyes of the beholder” were happily dispensed with, unless you count a giant microphone; Lenin calls this “Revolution as an Art Form.” Bricolage, in other terms.

I call it AASD, American Attention Surplus Disorder. Americans have always been terrible at the kind of single-minded focus demanded by pundits and dictators, especially when it comes to marches and parades. Over and beyond those settings in which the People are made to confront an image, Americans prefer that setting where the People confront themselves, transparently present to themselves, as in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s idea of the community. The Community does not set goals but contemplates itself; the only theater they’ll accept is the one in which they themselves are the performers.

Theatricality over Absorption. Every time. The People transparent to themselves:

Inless it’s the Department of Transportation.

And remember: The Pennies: Mightier than the Sword!

WOID XXIV-47

June 18, 2025

Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson, “Episode 87: Nate Silver and the Crisis of Pundit Brain” (Transcription); Citations Needed, September 18, 2019; https://citationsneeded.medium.com/episode-87-nate-silver-and-the-crisis-of-pundit-brain-fab3eca9c2e4; accessed June 15, 2025.

David Wallace-Wells, "Protest Is Underrated," New York Times (June 14, 2025); https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/14/opinion/ice-protests-la.html; accessed June 18, 2025.

cf. also Sigmund Freud, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur [Civilization and its Discontents] (Wien: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag), 1930.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, La Pensée sauvage (Paris: Plon, 1962), p. 26; see also Sigmund Freud, „Formulierungen über die zwei Prinzipien des psychischen Geschehens“ [“Formulations Regarding the Two Principles in Mental Functioning”], 1911; Gesammelte Werke, Band 8, Werke aus den Jahren 1909-1913 (London: Imago 1943), pp. 230-23.

Max Horkheimer, “Excerpt 1: On a major tendency of the enlightenment” (1926); marginal notes to Max Horckheimer, “Einführung in die Philosophie der Gegenwart (Vorlesung)” (1926), Gesammelte Schriften, Band 10 (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1990), 210-211, translated by James Crane, Substudies, June 17, 2025; jamescrane.substack.com/p/on-the-method-of-the-history-of-philosophy; accessed June 17, 2025.