And this is why I find comparisons with the French Revolution useful: not only because it defined the paradigms of Democracy but because, more than the American Revolution, it elaborated theories and arguments to hide the contradictions and conflicts inherent in democratic practice, conflicts that are still our own, unresolved, in Art, even.

Take the revolutionary politician Barère de Vieuzac. Someone once called him “The most seductive monster I’ve ever met,” which would put him on par with a few museum directors today. Barère’s strength was reconciling conflicting factions and concepts by diplomacy and charm. That the factions and concepts were irreconcilable did not particularly bother him; as Jean-Paul Marat noted with his usual bitterness, “He swims between two tides to see which side will emerge victorious.”1 Or, to quote Maxwell Anderson, museum director, addressing the present quandaries of museum directors not himself:

“If someone is truly a person of moral courage, they’re not likely going to end up being a museum director. The modern museum director is typically someone who’s good at balancing multiple concerns and stakeholders.”2

Barère’s career in Culture and Compromise got an early start with his promotion before the National Assembly of a series of petitions from Jacques Louis David and from the Commune des Arts, a group of junior members of the Royal Academy of Art that wanted to reform the institution itself, especially the rigid admission criteria for the Salon of painting and sculpture held every other year in the Louvre. On August 21, 1791, Barère reported back to his fellow lawmakers:

“Art must recognize only the privileges decreed by nature.

That equality of rights which forms the basis of the Constitution has allowed every citizen to put his thoughts on view. Equality before the law means every artist is allowed to show his work: his paintings constitute his thought; a public display constitutes his permission to publish.”

[…]

By these means you will see a crowd of talented men come forth from their darkest alcoves with precious works that privilege has kept from public view.

« Les arts ne doivent reconnaître que les privilèges décrétés par la nature.

L’égalité des droits qui fait la base de la Constitution a permis à tout citoyen d’exposer sa pensée ; cette égalité légale doit permettre à tout artiste d’exposer son ouvrage : son tableau, c’est sa pensée ; son exposition publique, c’est sa permission d’imprimer.

[…]

Par ce moyen vous allez voir sortir des réduits les plus obscurs une foule d’hommes à talent, et des ouvrages précieux que les privilèges éloignaient des regards publics. »3

Here again, as in my previous post, we can detect a contradiction between equality of rights and “natural” privilege, identified once again with “genius.” “Talent” and “genius” in the French Revolution were to provide the justification for de facto inequality, as they provide it today. Even today official reports from the French Ministry of the Interior—no less—quote Barère’s statement as a foundation of the French Nation. In one such report the quote follows an explanation that makes telling use of the historical present:

“The Salon, open until now for members of the Royal academies alone, and to certain privileged artists, is from now on accessible to all artists; the highly hierarchical systems that previously structured the Academies are dismantled: from now on all artists have a chance to join the exhibitions and institutes and, to a certain extent, multiply opportunities to join the bourgeoisie by patronage and the sale of their work.

In July, 1791 [sic] Bertrand Barère pleads, “That equality of rights,” etc.

« Les Salons, seulement ouverts jusqu’à présent aux membres des Académies royales et à certains artistes disposant de privilèges, sont dorénavant accessibles à tous les artistes, les systèmes très hiérarchisés qui structuraient les Académies sont démantelés : désormais tous les artistes ont une chance d’intégrer les expositions et les instituts, et d’une certaine façon, par le mécénat et les ventes de leurs œuvres, multiplient les occasions de pénétrer davantage la bourgeoisie.

Bertrand Barère plaide en juillet 1791, : “L’égalité des droits…” », etc.4

Never mind that Barère’s speech is misdated; or that the passage preceding it is fiction. The statement, to quote the historian Michelet over a hundred and fifty years ago, represents “Our contemporary creed, which the Revolution set out to put into practice (« notre credo moderne, que la Révolution entreprend d’appliquer »).5 The confusions and conflicts of the French Revolution turn into solutions, inviolate conquests of Democracy, not what should have been but what is today. We are all equal before the Laws of Genius and Talent. Likewise, Back in 1989, among the flurry of State-sponsored publications celebrating the bicentenary of the Revolution, one art historian concluded his article with a quote from the Commune des Arts which, we were meant to believe, accurately described the lasting achievements of the Revolution as they stand today (the Revolution, whatever else, did not believe in netiquette):

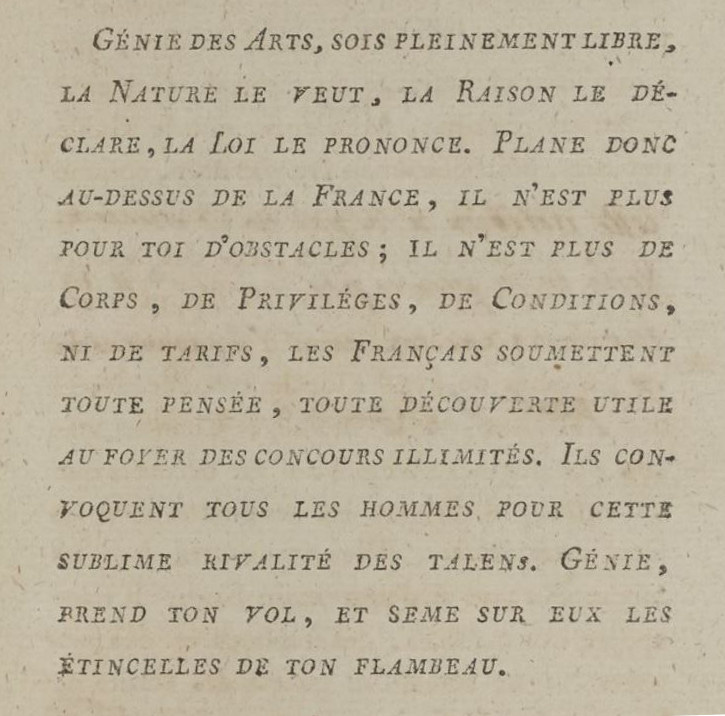

“GENIUS OF THE ARTS, STAND FULLY FREE. NATURE DEMANDS IT, REASON DECLARES IT, THE LAW PRONOUNCES IT. THEREFORE, SOAR ABOVE FRANCE, FOR YOU THERE ARE NO MORE OBSTACLES; THERE ARE NO MORE BODIES, PRIVILEGES, RESTRICTIONS NOR TARIFS. THE PEOPLE OF FRANCE SUBMIT EACH THOUGHT, EACH USEFUL DISCOVERY TO THE FIRE OF OPEN COMPETITION. THEY INVITE ALL MEN TO THIS SUBLIME RIVALRY OF TALENT. GENIUS, TAKE FLIGHT AND SCATTER UPON THEM THE SPARKS OF YOUR FIRE.”6

And now, from Barère, the fine print:

“The Salon at the Louvre is the printing press for paintings, so long as social values and public order are respected.”

« Le salon du Louvre est la presse pour les tableaux, pourvu qu’on respecte les mœurs et l’ordre public. »

It would be hard to overestimate the import of this caveat, nor its subsequent metamorphoses. “Public order” was no abstraction, it was a stricture against incitement to public disorder. The winter of 1789-90 had witnessed a heated debate over this issue, provoked by attempts to perform Marie-Joseph Chénier’s virulently anti-royalist play Charles IX. Whether Chénier had respected contemporary values depended on whether one believed oneself to be living in a society whose values were monarchical or republican. In the parlance of museum directors today, the issue hinged on the kind of stakeholder one had to decide to join.7 In 1789 the issue would eventually be resolved in blood. With museums, probably not. Either way, “Values and public order” would never stray from their original meaning: good behavior in conformity with the values of the State, and that would include aesthetic values.

In that light we need to clarify, as in our previous post, the meaning of the word “Genius” (or rather, “GENIUS”), in its new context.8 The tract from the Commune des Arts was by Jean-Bernard Restout, a member of the Academy who had been agitating to open up the selection process of the Salon since 1771. Dale Van Kley has argued that many aspects of French revolutionary ideology are indebted to practices of resistance to the authority of the Catholic Establishment developed in the religious sect of Jansenism from the seventeenth century on.9 Restout himself came from a long line of Jansenist supporters. But it would be out of place to read his tract as an act of resistance to the newfound National authority, invoking Genius as an affirmation of the artist’s right to transcend social values, let alone the authority of the State. “Genius” for Restout was not the “Genius” of the Encyclopédie as previously described. It was the ingenium of Saint Augustine, the Church Father whose writings had the greatest influence on Jansenism:

“That ingenium whereby the artificer may take his art, and may see within what he has to do without.” [Confessions XI.5)

Genius was not an individual’s refusal or transcendence of Authority in general, but rejection of illegitimate authority in favor of direct, unmediated, “natural” submission to a higher, legitimate authority. Acceptance or refusal was available to the community as a whole; this was the same Genius that, under the name of Daimon, was said to have inspired Socrates, the subject of a well-known painting:

“No man, considered as So-and-so, can be a genius : but all men have a genius, to be served or disobeyed at their own peril.”10

“Revolution” as submission to the State of Affairs: it’s a posture all-too-familiar today among artists, art critics, and most of all museum directors. And it begs the question, what would a revolution against the “Revolution” look like? But that, dear reader, is another question for another post.

Jean-Paul Marat, « Convention Nationale », Le Publiciste de la République Française no. 242 (Dimanche, 14 juillet 1793), p. 7.

Tom Seymour. “Leading museum directors to debate whether institutions can remain objective in a politically volatile world.” The Art Newspaper, August 19, 2022. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/08/19/how-should-museums-lead-in-a-volatile-world-icom-conference-prague

« Séance du dimanche 21 Août », Réimpression de l’Ancien Moniteur Mai 1789-1799 Vol. 9 (Paris : Plon Frères, 1854), pp. 452-53.

République Française. Premier Ministre, Rapport annuel de l’Observatoire de la Laïcité 2016-2017 (Avril 2017), p. 320.

Jules Michelet, Histoire de la Révolution française [1868], « Introduction ».

[Jean-Bernard Restout], Pétition motivée de la Commune des arts à l’Assemblée nationale pour obtenir la plus entière liberté de Génie par l’établissement de concours dans tout ce qui intéresse la Nation les Sciences et les Art. [Paris :] Chez Guilhemat, Imprimeur de la Liberté, rue Serpente, No 23. nd. [Dated by hand: 19 Janvier, 1791], p. 15.

Jonathan I. Israel, Revolutionary Ideas : an intellectual history of the French Revolution from the Rights of Man to Robespierre (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 68-70.

See “The Thomas Crow Affair,” WOID XXII-35 (August 14, 2022).

Dale Van Kley. The Religious Origins of the French Revolution: From Calvin to the Civil Constitution, 1560-1791. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1996; John Goodman. “Jansenism, ‘Parlementaire’ Politics, and Dissidence in the Art World of Eighteenth-Century Paris: The Case of the Restout Family.” Oxford Art Journal Vol. 18, No. 1 (1995), pp. 74-95.

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “Why Exhibit Works of Art?” Why Exhibit Works of Art? (London: Luzac & Co., 1943), 38.