Review Essay:

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England

October 10, 2022 – January 8, 2023

https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2022/tudors

Admissions: Up to $30.00 for the un-New Yorkers. New Yorkers get in “free” by way of major harassment.

Part One

In 1919 the cultural historian Johan Huizinga wrote,

The great divide in the perception of the beauty of life comes much more between the Renaissance and the Modern Period than between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Huizinga’s a useful corrective to the ongoing exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art — or rather two exhibitions, as is common nowadays: one the outcome of informed curatorial decisions and the thoughtful disposition of irrefragable material, the other the official version dreamed up by boardroom suits, publicists and the critics who love them. If there’s any “perception of the beauty of life” in The Tudors, it’s got little to do with the Renaissance as understood by the PR Department and the Persons who Lunch. Huizinga adds:

The turnabout occurs at the point where art and life begin to diverge. It is the point where art begins to be no longer in the midst of life […], but outside of life as something to be highly venerated, as something to turn to in moments of edification or rest.1

“Art and life diverge;” “highly venerated;” edification and rest:” sure sounds like a museum director’s dream to me. A year later, Huizinga would drive the point with the hammer of sarcasm:

"The dreamer […] recites his credo. The Renaissance was the emergence of individualism, the awakening of the urge to beauty, the triumph of worldliness and joie de vivre, the conquest of mundane reality by the mind…”2

The Tudors had individualism to spare, but I wouldn’t call it edifying; their joie de vivre seems more of a joie de voir crever les autres, of the type Huizinga identified with the Late Middle Ages. The curators take a Halloween pleasure in piling up the quirkiness and the gore. Henry VIII is a weighty presence; his suit of armor’s on display in case you’ve ever wondered what people saw on him:

Then there’s the juicy signage, as for the portrait of Mary Neville, Lady Dacre, painted to commemorate her late husband, executed. It’s not really a portrait in the Renaissance sense of being a transparent representation, “The depiction of an individual in his own character,” to quote myself quoting John Pope-Hennessy. Rather, it’s an “image” in the Medieval sense, a palpably symbolic judgement.3 Just to make sure, the artist, Hans Eworth from the Netherlands, inserts a realistic Renaissance-y portrait of Mary’s late husband in the upper left corner, the visual equivalent of air quotes. It’s as if the artist were telling us he, too, has mastered those new-fangled Renaissance tricks and intends to keep them at arm's length.

The same can be said of the “Sieve Portrait” of Elizabeth I by Quentin Metsys the Younger, Flemish. The background holds a plunging diagonal worthy of Tintoretto while the foreground figure is as shallow as tapestry, a “furniture-and-costume piece in which pattern takes the place of style.”4 The two pictures, Elizabeth and Mary, were painted thirty years apart, a fact not obvious from their placement in the galleries: in either case it's the consistency of the Tudor style over time that's noteworthy, not the fact that so many of the artists on display were foreign-born.

A large number of the works on display consist of what the Renaissance lover moyen sensuel (if you’ll pardon the redundancy) would call “minor arts:” clothing, embroidery, calligraphy and such. Much of it it is “mere” craft in the narrow sense of being without affect, like the “Seadog” Table of 1528, which reads like a nineteenth-century take on sixteenth-century French furniture, though it’s actually a sixteenth century take on sixteenth century French furniture. It’s cold as as a…

Arguably this show should have been titled Art and Majesty in Mannerist England since in Mannerist Art, style itself is a conscientious technique. Then again, Mannerism isn’t boffo at the box-office, it’s a fly in the ointment of traditional Renaissance studies: if the Renaissance inaugurates all those wonderful projects that make us what we are today (assuming we’re the kind of visitor the Met thinks we should be) then Mannerism represents a step backward, a kind of Debbie Downer of Art History, Art backsliding into Craft. At any rate the preference for affectless craft techniques over individual styles is palpable throughout this show; palpable even in the handful of studiously “objective” portraits by Hans Holbein, the closest this show comes to the traditional concept of a Renaissance style; and in Pietro Torrigiano’s subtly angled bust of John Fisher (beheaded 1535). Torrigiano himself is remembered for breaking Michelangelo’s nose during a drawing session in Florence; he died at the hands of the Spanish Inquisition. The two events are, apparently, unrelated.

Part Two

In a classic feminist text the late Joan Kelly-Gadol asked, “Did Women have a Renaissance?” Kelly-Gadol held the word Renaissance to its usual connotations: progress, positive change, the empowered self. These criteria might apply to the experiences of men; for women, she argued, the Renaissance was an era of reduced opportunities and freedoms, a time when, to quote S. Boynton, “just about any turkey could do anything.” So long as the turkey was a tom.5

This argument goes to the confusion at the core of The Tudors. After all, there were plenty of powerful women in Tudor England: Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots, Queen Mary of England (commonly known as Bloody Mary), Mary, Lady Dacre. These are well represented in the Met’s galleries. In addition, a good part of the exhibition is devoted to crafts, an area traditionally the province of women, at the very least an occupation from which women in the Early Modern Period were not systematically excluded as they were from the “Fine” Arts. If, as Kelly-Gadol asserts, “there was no ‘renaissance’ for women, at least not during the Renaissance” [p. 176], then perhaps the Tudor Age was no Renaissance to begin with.

I was listening in on a group of patrons, those privileged members the Met sees as its primary audience. The words “Hans Holbein” kept bobbing up like a lifesaver for a privileged passenger on the Titanic of Art History. Holbein’s portraits, in their minds, were what The Tudors is all about: strict, realistic accuracy, the individual character transparently accessible to the contemplating mind. In sum, the Renaissance as imagined in traditional Art History and the positivist ideology it upholds:

Perversely, The Tudors lacks that transparency which to the traditionalist art historian (say, Erwin Panofsky) puts Renaissance representation — “pure” representation, unbesmirched — above historical and social contingencies. The Tudors is anthropological in the best sense of the term: no narrative can get to the bottom of it (« aucune histoire ne l’épuise »), least of all the simplistic narratives of Art Appreciation.6 Hence the fractures and contradictions, the “spirit of disjunction,” the “irresistible urge to ‘compartmentalize’” that to Panofsky marked the very antithesis of Renaissance intellectual practice; or the apparent lack of that humanist poise and rationalism that literary critics love to uphold as the dominant strain in Elizabethan prose and poetry.7

As Michel Foucault reminds us, the concept of periodicity rests on untenable assumptions, not least the assumption of historical continuity under any name, either of progress, or Renaissance, or regression. Rejecting a linear reading of “significant” phenomena, Foucault sees in History a series of interlocking, contrasting, even conflicting elements: “The story told will not be here and there the same one.” (« Ce n’est pas la même histoire qui, ici et là, se trouvera racontée. ») Likewise, the story told by The Tudors is not the same art appreciator’s tired story, but a reordering of similar-seeming elements and activities providing new configurations and meanings even when the objects seem Renaissance-like. It’s a process similar to that which Arthur Danto calls affines, except that Foucault demands structural analysis as a process whereas Danto is content with static ontologizing. The task for Foucault, unlike Danto, is not to hypostatize Art, let alone Art History, but to ask

“What strata need to be isolated one from the other? […] What criteria for periodization are to be adopted for each?”

« Quelles strates faut-il isoler les unes des autres ? […] Quels critères de périodisation adopter pour chacune d’elles ? »8

If there is something patriarchal in Art History it’s not merely that it restricts itself to productions traditionally associated with men, but that it chooses to ignore the epistemological fractures in the objects, activities and individuals it approaches, to the point where class tensions, gender tensions, ideological tensions become mere reflections, externalities. On all levels the Tudors reveals attitudes and processes that are simultaneously affirmative or negative for women: in style, in content, in their intended audience and in the opportunities and restraints available. We have seen how the portrait of Lady Dacre and the “Sieve” portrait consciously borrow divergent systems of representation, and we can expect to see the same conflicts in all fields: formal tensions, social tensions, psychological tensions. If anything, the Tudor Age is best called a “Counter-Renaissance.”

Take handwriting. By the mid-fourteenth century the tasks of the scribe had passed from the traditional monk or nun in the cloister to underpaid, overworked speedwriters, often women or debt prisoners. Within a century the printing press had crushed this last resource while offering alternative options, such as type-setting, which was occasionally tasked to women.9

By the sixteenth century however, a new profession had arisen, that of the writing-master offering a model for social advancement through the propagation of humanist values and instruction in those scripts that were meant to indicate a secretary’s good breeding and worldliness. Esther Inglis of Edinburgh occupied a rung on that ladder, somewhere between a writing-mistress, the owner of a secretarial school, and a courtier; from 1604 on she produced a series of books using the new-fangled “humanist” script that was slowly gaining acceptance in England, the “Sweet Roman Hand,” as Shakespeare called it:

In 1924 the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein defined the central role played by writing in the social formation of women. From the moment a young girl was handed a pen (with its obvious phallic reference), she was given the option to compete with men in what Klein's admirer Jacques Lacan would later call the “Symbolic Order:” the world of communication, interpersonal relations, acceptance of the Law. Children, according to Klein, were now confronted with the need and opportunity to become active, to assume agency, with “the necessity for abandoning a more or less passive feminine attitude, which had hitherto been open to [them].”10 One thinks of the way men and women alike assume non-traditional gender roles in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, or of Mary Dacre’s role in the rehabilitation of her husband and in the painting she commissioned, or Elizabeth I, or any woman in the Early Modern Age entering the field of male endeavor through a vocation of voluntary servitude.11 Or of a skilled writer of humanistic script — say, Esther Inglis — taking up the challenges and rewards of a crossed vocation. Elizabeth I is best known, who learned the Roman hand from the preeminent Elizabethan humanist and writing-master, Roger Ascham.

This contradicts Kelly-Gadol’s assessment that the Renaissance “establish[ed] chastity as the female norm and restructure[d] the relation of the sexes to one of female dependency and male domination.” Those are the anachronistic assumptions of the 'seventies. First, a causal relation between “chastity as a female norm” and “female dependency and male domination” is taken for granted. Second, “Women’s Liberation” is equated with liberation from sexual repression. Finally, Kelly-Gadol conflates “Chastity” with “asexuality.”12 The word Chastity derives from the Latin Castitas, “integrity,” “respect for one’s own worth.” In today’s parlance it means “don’t be a whore,” without necessarily bringing sex into the equation: not a passive virtue but a form of autonomous agency.

Or the making of crafts. Visiting The Tudors, one is struck by the ease with which religious affect, religious sentimentality, even, flows through the most mundane articles of everyday life. The dissolution of monasteries and nunneries in 1536 had released immense productive and creative forces, channeling affects originally directed toward religious expression into lay endeavors and creations. Mary, the incarnation of the chaste and contemplative life, gave way to Martha, the symbol of the treasured, active life.

“Chaste” would have been applied as well to the sweet Roman hand practiced by Inglis. Back in 1366 the Italian poet Petrarch complained to the humanist politician Coluccio Salutati that the professional scribes on which they both relied had the pretension to ply their mundane craft as an individual style, an artistic statement,

“…a digressive and luxuriant letterform, such as that of the writers or, more truly, of the painters of our time […], as if it had been invented for something other than reading.”

“…vaga quidem ac luxurianti litera -- qualis est scriptorum seu verius pictorum nostri temporis […], quasi ad aliud quam ad legendum sit inventa.”13

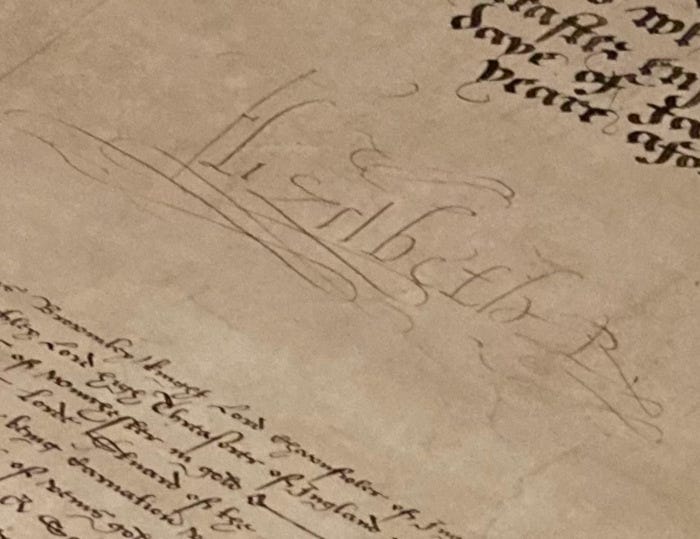

“Chastity,” in the calligraphic sense, was the classical, humanist and, yes, Renaissance form of the Roman hand. Yet neither Chastity, nor Humanism, nor Renaissance have the final word. In this show it belongs to a gift roll sent to Elizabeth in 1585, somewhat equivalent to an office holiday card for royalty:

The dedication and grateful thanks are, appropriately, in the Medieval secretary hand, the kind of thing no proper humanist would abide. Queenie’s signature is in a humanist hand, except it’s in the hand of someone who’s going to do whatever she goddam pleases, so: Did women's power and agency decline in the Tudor Age? Did they expand? What matters for us today, is that power and agency — of women as of men — were very much in play, as they should be, then and now. Virgin Queen, my ass.

Paul Werner (aka Murf the Serf)

December 11, 2022

Johan Huizinga, The Autumn of the Middle Ages, translated by Rodney J. Payton and Ulrich Mammitzsch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), p. 40.

Huizinga, “The Problem of the Renaissance.” Men & Ideas. History, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance (New York: Meridian Books, 1959), p. 243.

cf. Dominic Olariu ed., Le portrait individuel. Réflexions autour d’une forme de représentation, XIIIe au XVe siècles. Tagungsakten, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 6-7 fév. 2004 (Bern: Peter Lang , 2008), esp. Paul Werner, « Katherine l'Africaine ou les ruses du Dessin », p. 235 ; https://www.academia.edu/196915/

Ellis Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 to 1790. Pelican History of Art (Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, 1953), p. 29.

Joan Kelly-Gadol, "Did Women Have a Renaissance?" in Becoming Visible. Women in European History, ed. Renate Bridenthal and Clandia Koonz (New York: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1977), 175-201; Sandra Boynton, The Compleat Turkey (Boston: Little, Brown: 1980), p. 22.

Roland Barthes, Critique et vérité (Paris : Éditions du Seuil, 1966), pp. 48-49. Barthes is referencing the structuralist (viz., dialectical) approach of Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Erwin Panofsky, Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art (New York: Harper and Row, 1972,) p. 106; Hiram Haydn, The Counter-Renaissance (New York: Charles Scribners’ Sons, 1950), pp. 27 sqq.

Michel Foucault, L'Archéologie du savoir (Paris : Gallimard, 1969), pp. 11, 10; Claude Lévi-Strauss, La Pensée Sauvage (Paris : Plon, 1962), p. 174 ; Arthur C. Danto, Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective (Berkeley-Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1992), p. 53.

Armando Petrucci, “Scriptores in urbibus:” alfabetismo e cultura scritta nell'Italia altomedievale (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1992); Giovanni Boccaccio, “Epilogue,” Genealogie deorum gentilium de Montibus, Silvis, Fontibus, Lacubus, Fluminibus, Stagnis seu Paludibus, de diversis nominibus maris (1373).; Daniel Berkeley Updike, Printing Types. Their History, Forms, and Use. A Study in Survivals (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1937), p. 9.

Melanie Klein, “The Role of the School in the Libidinal Development of the Child,” Love, Guilt, and Reparation, and Other Works, 1921-1945 (New York: Dell, 1975), p. 60.

Max Weber, »Konfession und soziale Schichtung, « Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus, in Archiv für Sozialwissenschaften und Sozialpolitik 20. Bd., Heft 1, (1904), S. 1-19.

Kelly-Gadol, pp. 176, 189.

Petrarch, Epistolae familiares XXIII, 19, 8 (1336); quoted in Berthold L. Ullman, The Origin and Development of Humanistic Script (Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 1960), pp. 13-14.