Lives of the Gods. Divinity in Maya Art.

New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 21 - April 2, 2023. Fort Worth, TX: Kimbell Art Museum, May 7 – September 3, 2023.

Exhibition Catalog:

Lives of the Gods. Divinity in Maya Art. Ed. Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, James E. Doyle and Joanne Pillsbury. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

Access:

If you are an out-of-towner, be prepared to pay up to $30.00 for admission to the Met. If you’re a New Yorker, bring ID, and expect to be subjected to the “embarrassment factor,” the museological equivalent of a traffic stop.

****

Lives of the Gods is yet another “high concept” show, a big budget production that sets out to appeal to the widest possible audience by means of technology and generic effects, or rather by means of generic effects by means of technology since all technology is, sui generis, generic. The galleries are scattered with large projections of tropical forests, the room are sanitized and spacious, too spacious for the small number of works on display: wide enfilades more appropriate to a ceremonial center than to an active Maya community. This is an environment in the style of Zaculeu, a Maya site in the Guatemala highlands that was restored in the late forties by the United Fruit Company: it bears a remarkable similarity to a corporate headquarters.

The theatricality is stifling, down to the over-dramatic lighting, the kind you’d expect from a a Broadway show or a Baroque chapel. Considering the Maya’s reputation for bloodthirst it’s surprising none of the portraits have a spotlight up their nostrils as in cheap horror movies.

The same aesthetic that’s been applied to the overall organization of the exhibition is applied to individual artworks, which in many cases are displayed so as to force the viewer onto a single axial approach in the grand Baroque manner, despite the fact that many of those works displayed as upright panels were originally lintels facing down from the ceiling of a narrow temple doorway. The choice of works and the display of the works are determined by The Concept, rather than the other way around. And in case you didn’t get it, The Concept has been laid out in the e-pages of the New York Times:

“Similar images appear repeatedly in Maya elite political and religious art, which is what the art at the Met is. They are, among other things, superbly imagined advertisements for power through intimidation.”1

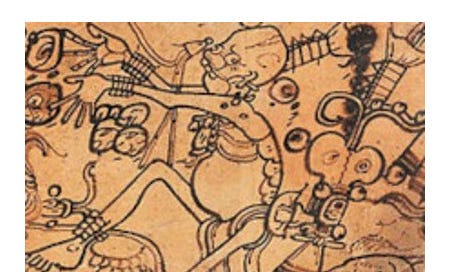

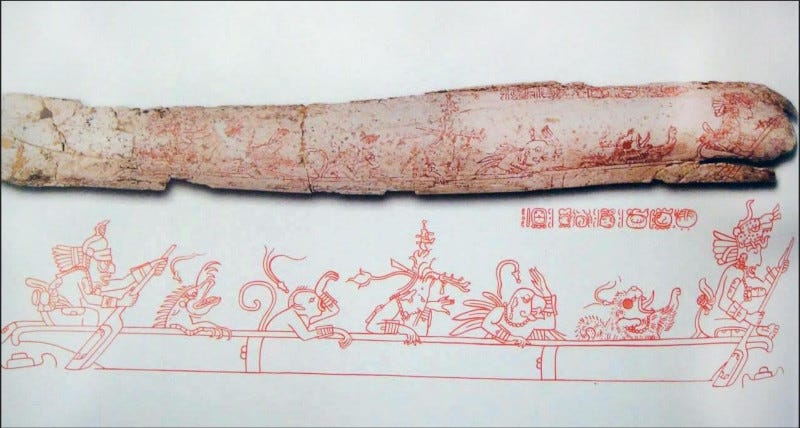

Is this what Maya art’s about, or merely what Lives of the Gods has decided it’s about? Where are the linear, psychologically penetrating portraits in stone or in fresco like those at Bonampak, at once conventional and deeply sensitive? Where, the wit and humor? I miss the tiny human bone from Museo Morley in Tikal (Guatemala), engraved with an image of the Maize God crying as he’s led into the underworld by cheerful animals: an iguana, a spider monkey, a parrot and dog, with a couple of gods at the paddles. The hand gestures alone will break your heart:

Just not box-office. The message from Images of the Gods is, that the Museum, not the original creators, is best equipped to understand, and therefore to hold these objects at their true worth. An exceptionally large number of works in this show are signed, which, apart from their aesthetic appeal, makes them more valuable only from an Eurocentric point of view. The designated draw of the show is the Throne from Yok’ib (Piedras Negras, in Guatemala), duly signed by K'in Lakam Chahk and Patlajte' K'awiil Mo[…] — the last part is erased.

The Throne meets other criteria of traditional Eurocentric aesthetics as well. Like any solid piece of public art in the academic tradition (say, a Soviet-era statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky) it’s simple in the design and in the details, consistent in repeated symmetries, in particular the two facing figures and the organization of the patterns on either side, mirrored along a central vertical axis: Baroque in the Grand Manner of Versailles. The word Baroque, incidentally, is thought to derive from a word first applied to misshapen, asymmetrical, natural objects like pearls, or the engraved shells the Maya prized:

If you’re going to go for a Baroque feel, make sure it’s the right one.

In addition, the presence of the Throne from Yok’ib has drawn the ire of Indigenous communities in Guatemala, who filed a complaint with the Guatemalan Government, claiming the object had been sent to New York under false pretenses and should have been returned—theirs seems to be a justified fear the Met is planning to turn the temporary loan into a permanent loan, much as it did for another stela from Yok’ib (Stela 5, Ruler receiving a Noble) that’s been at the Met since 1970, the kind of loan you can’t refuse. One gets a feeling this show was planned around an aesthetic of which the Yok’ib Throne had the misfortune to be a perfect example. Perhaps it’s too much to suggest that “getting” the Throne was a motive behind this show, which adds very little to The Blood of Kings: A New Interpretation of Maya Art that was shown at the Kimbell Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art back in 1986. In fact, an alarming number of objects on display today were on display back then. The result today is a kind of affective numbness, with little sense of the rambling, layered asymmetry, the complexity and crowding, the reaching, the lived-in feel, the excitement of the original show, or the raw emotion that’s common in Mayan culture. The galleries are partitioned by high pierced walls reminiscent of 'sixties civic architecture, apparently meant to evoke the honeycomb roof at Yaxchilan:

Except at Yaxchilan you’re more likely to be dodging poo-poo from howler monkeys while you trip over trees, still more satisfying than dodging overwrought concepts from art critics and curators.

****

The great Black Marxist cultural critic Stuart Hall would have designated art critics as “secondary definers” whose job is not merely to pass down information from above, as I myself have erroneously argued. Their task, rather, is

“the presentation of the item to its assumed audience in terms which, as far as the presenters of the item can judge, will make it comprehensible to that audience.”

By that definition the critic plays

“a crucial but secondary role in reproducing the definitions of those who have privileged access, as of right, to the media as ‘accredited sources.’”2

The task of the critic, the “secondary definer,” is to provide a framework for the would-be museum-goer; to make the intention behind the exhibition accessible as the one meaning of the exhibition. Secondary definers get their information from “first definers,” for instance the museum's press bureau or the organizers of an exhibition. Those are not necessarily the curators of the show but often a museum director, or sponsors, or an interested trustee. Those are the ones who “command the field,” as Hall phrases it. How else to explain the following, again concerning Lives of the Gods and again from our critic at the New York Times:

“That aggression [i.e., aggressiveness] complicates perceptions of this art’s astonishing formal and imaginative beauties, and of beauty itself as a saving grace.”

This reads like that self-exoneration of which museum directors have become masters of late: Beauty as the excuse for all the depredations committed in the name of Beauty. Depredations committed by Museum directors, that is: the Maya had nothing to do with this, they weren’t particularly interested in Beauty, only in making sense of things.

Fortunately, and contrary to what many a conspiracist may believe, even the first definer’s narrative is never free of cracks and contradictions; the second definer’s is often so incoherent it’s the easiest thing to take apart, which is why I often discuss it as my first line of attack. Critics—at least those of the Times—speak with no voice of their own; museum professionals speak with many voices, some of which are worth hearing if you know how to listen. Sometimes, as is here the case, there are several curators talking over one another.

Take a look at the ceramics in this show, for instance, and you’ll enter another world—certainly another one than what the Times describes. Unlike the grand narrative of the show as a whole, the organizing principle behind this section is strictly typological: pots and vases are selected and displayed according to shape, or size, or theme, or imputed function.

The four lidded vessels from El Zotz in Guatemala are noteworthy for the tense dynamic of volume against plane, the presentation of three-dimensional forms in three-dimensional and two-dimensional space at once, and of course the very existence of a set is impressive. Yet I miss the lidded pot from the Museo de San Miguel right outside Campeche, Mexico, one of the great works of Maya Art for its close blending of form and narrative, a god-serpent rising from the primal muck:

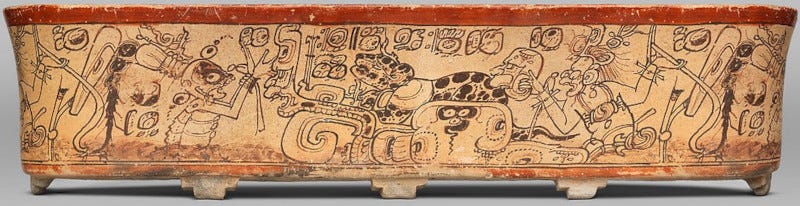

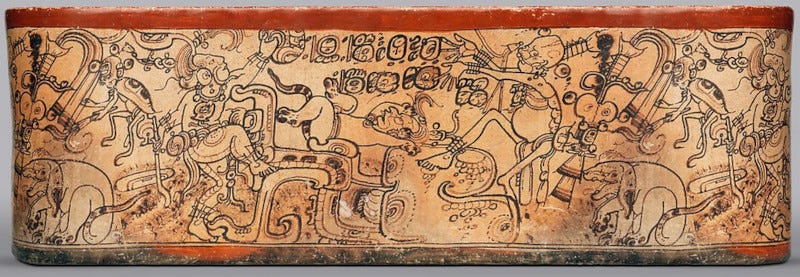

And then there are the vases, and they’re so divergent from anything in this show that they beg us to rewrite the given view of Maya culture, top to bottom:

Stylistically they’re different from anything else in this show: a blooming, buzzing confusion of signs and symbols with no logical connection apparent between their elements. This divergence demonstrates the failure of a formalist approach to Maya material culture: There is no Maya Formwollen here, no Will-to-Form, at least not in a formalist understanding of form.

*****

In another cringe-worthy comment the Times critic adds:

“Culturally, the Maya invented a hieroglyphic writing system, still not fully deciphered."

It’s been known in fact for the past half-century that the Maya system of writing is not hieroglyphic in the sense of a strict correspondence of image to idea, word to meaning. The Maya system of writing is not, strictly speaking, a system of writing but a complex web of signification through visual images of all sorts. This has, over the past fifty years, become apparent, painfully so, to those who would imagine the Maya system of visual expression is some kind of alphabet in our sense of the word, a one-on-one equivalence of sign and signified.

In the carved lintel from Yaxchilan, for instance, one reads repeated rhyming patterns that can be made to signify at once the spatters of blood, the spots on a snake’s skin, and the symbolic sense of either. These games are duplicated in the inscriptions proper, which are just as likely to be a combination of syllabic indicators, of verbal and visual puns, word-games, picture games, mind games, an unstanched flow from sign to signification. To “read” these forms is to enter an underworld akin to African-American signifyin’, or the images in the margins of European Medieval manuscripts.3 The meaning of the performance is understood only in the context of the performance of meaning. The bone from Tikal, for instance, is one of a larger set of inscribed bones, so that the “story” can be read at once on a single bone and by reorganizing the bones into patterns, the pattern of the body rising, shinbone to the hip-bone, but first you gotta collect the bones in the Valley of Death. Instead of Will-to-Form, in Maya Art we find, as Nietzsche found in his own culture, a “Will-to-Mean,” a desperate quest to put together the pieces of the world:

Man, the most stoic of animals and the one least immune to suffering, does not reject suffering as such; he wills it, he even seeks it out, provided the meaning, the purpose of suffering have been explained. The meaninglessness of suffering, not suffering itself, has been the curse which has so far weighed over mankind.

Der Mensch, das tapferste und leidgewohnteste Thier, verneint an sich nicht das Leiden: er will es, er sucht es selbst auf, vorausgesetzt, dass man ihm einen Sinn dafür aufzeigt, ein Dazu des Leidens. Die Sinnlosigkeit des Leidens, nicht das Leiden, war der Fluch, der bisher über der Menschheit ausgebreitet lag.4

As Rilke said, from his own culture, what we love about Beauty is, that it serenely disdains to destroy us. The Maya had no such illusions.

WOID XXIII-05a

Holland Cotter, “The Met's Maya Show Asks: Can Art Ever Be Innocent?”, New York Times (January 19, 2023). https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/19/arts/design/maya-art-mesoamerica-metropolitan-museum-beauty.html

Stuart Hall, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke and Brian Roberts, “The Social Production of News,” in Media Studies. A Reader, second edition, ed. Paul Marris and Sue Thornham (New York: New York University Press, 2000), pp. 646, 650.

Friedrich Nietzsche. Zur Genealogie der Moral. Eine Streitschrift, Zweite Auflage (Leipzig: C. G. Naumann, 1892), pp. 182-83.

Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Signifying Monkey: a Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism (New York : Oxford University Press, 1988); Michael Camille, Image on the Edge. The Margins of Medieval Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).