Out-Rage

WOID XXII-39

[Conclusion of a two-part article]

Hendiadys, much? In a passage virally twittered of late, Hannah Arendt wrote:

“The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.”1

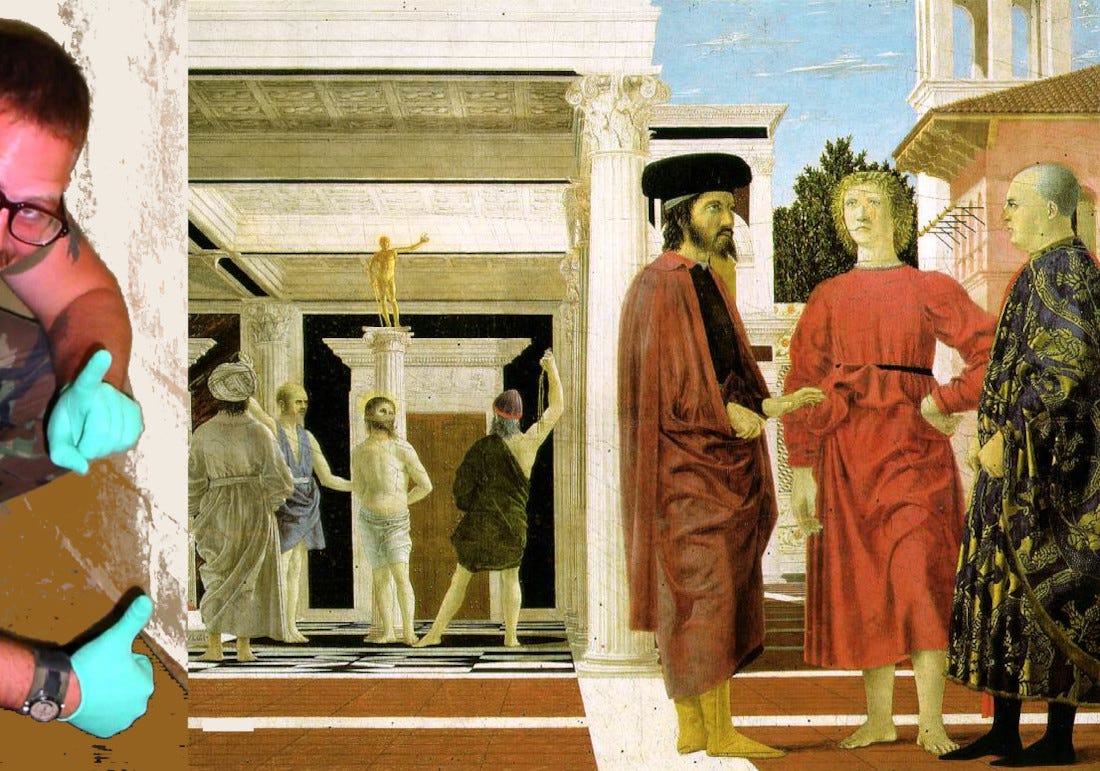

That means the good guys hold the Truth and them bad guys don’t, right? But as Paul Ricœur points out, Arendt is consistently hobbled by the limitations of her own philosophy: is “the ideal subject” those who can’t distinguish between fact and fiction or those who can’t distinguish between what’s true and what’s false? I’d say, rather, it's those who collapse the two distinctions. A painting, as Augustine reminds us, can be neither true nor false—or rather, it must be both at once. And Kant thought much the same: a fiction or a fact cannot be collapsed into the categories of True or False.2 To any but bigoted wackjobs a painting of Christ is a fictional narrative, whatever the truth of the events narrated; absent this it becomes a fount of absolute authority:

“Communication as practiced by museums [... …] is most often unilateral, that is, without the possibility of reply from the public, whose extreme passivity etc. […] ‘So intense is [the museum’s] communicative power…’,” etc. etc.3

The ideal subject of totalitarianism is the one who confuses the manipulative fictions of art with the proclamation of transcendental truth.

Someone like Jean-Jacques Lebel. Remember back when we’d all gathered to figure a way forward, and some unkempt kid was jumping up screaming, “We need a revolution, MAN!” and the kid’s dad was the College dean, or the Company EO? That would be Lebel, the only artist I know whose Wikipedia page lists his father’s accomplishments before his own. In May, 1968, according to Patrick Ravignant, Jay-Jay was running around the Odéon denouncing the commodification of Art while commodifying his own authority to denounce the commodification of Art by asking to be paid for interviews.4 Now the young hipster who in the ‘sixties staged happenings to denounce « Les squouaires américains » stages a “situation” that instead of denouncing American atrocities in Iraq stages them as self-evident. Jay-Jay’s got a soulmate, Kader Attiah, a curator and Beur [French citizen of Algerian descent] who has aggressively staged Jay-Jay at the Berlin Biennale—so aggressively that he leaves the public with no options to reply or to avoid “a maze of crude entrapment.” Gigantic blow-ups of those hideous selfies at Abu Ghraib block visitors’ access to the other works on display.5 The Iraqi artists who’ve been invited to exhibit have withdrawn in protest, as has a curator; an online petition was launched denouncing Attiah, and the art.

I sympathize. Those artists have experienced what I, a Jew, experience at Berlin’s Jüdisches Museum and elsewhere: not the mistakes of a single curatorial wanker, or the callous misprision of an incompetent artiste (although that, too), but systemic museological authoritarianism, “the insidious policies […] that are built into the very physical fabric of museums,” down to its architecture:

“To get to the displays you have to pass through a rat’s maze of angular passageways meant to reinforce your distaste and self-loathing; patterned very closely, in fact, on the ways the Nazis themselves liked to depict the Jews: a subterranean, tight-packed horde.”

What most upset the artists was, their work was accessible only by passing through Lebel’s piece. Kadeh countered that “no visitor of the [Biennale] exhibition was or is obliged to go through the installation,” but he has no way of knowing what the guards and staff are up to—or doesn’t care to know. Perhaps access is selectively enforced, as in the Jüdisches Museum, which is

“patrolled by blonde BDM-boys in tight black pants whose function is to selectively decide who, among the visitors, is worthy to be admitted.”6

Berlin’s museum staff know the moves as well as anyone. They can decide who will or will not be spared the experience, based on looks alone. Kaddeh calls his intervention a “reappropriation of dignity.” the Iraqis call it a reiteration of the humiliation of Iraqi People which it is, as surely as the Jüdisches Museum is a willed and ritual humiliation of Diaspora Jews: "Destruction of the self-esteem of weaker groups [...] is known to be one of the most powerful measures of collective psychic reprisal."7 What the Iraqis have endured is the same deadly drumbeat of microaggression most any Jew in Germany or Austria endures on a near-daily basis, under the condescending pretense of empathy. It’s what I call Out-Raging. It’s the same drumbeat my young Black students endure even in their Art classes or the Museum. Likewise museum pedagogy's structured around the idea that there are winners in Art History as surely as there are winners in History, and winners are not us because, what other reality is there?

In an early unfinished draft the Jewish-Russian poet Osip Mandelstam suggested there was a kind of freedom granted to Christian artists in the Middle Ages:

"Christian art is joyous because it is free, and it is free because of the fact of Christ's having died to redeem the world. One need not die in art nor save the world in it, those matters having been, so to speak, attended to.”8

Christ and the Saints: the Transcendental Losers who give us all permission to be losers, too. Except for those who can’t face being losers; whose work is a projection of their own sense of failure. Lebel and Kaddeh are French citizens; Kaddeh, as he admits, is scarred by his family’s experience at the hands of the French, the folks who re-invented torture as it’s practiced today, much as modern-day Germans are scarred by their inability to connect with their own past under any terms but their own lack of self-esteem. Kaddeh call his work as “repairing.” That’s the conundrum of 21st century culture: Who has the right to appropriate and who to repair? Who has the power? For Lebel, Kaddeh and so many others power comes from directing self-hatred outward to confiscate the pain of others: “If somehow, somewhere, one finds an object deserving of sympathy, it usually turns out to be none other than oneself.”9 What’s directed outward is not a sense of guilt but rather the denial of one’s own moral responsibility, an excretion of one’s own sense of powerlessness, a reappropriation of the power to inflict harm and humiliation. I call this “Out-Raging.” There ought to be a prize for this, the Salman Rushdie Prize.

Compare with Mandelstam who through his life consistently refused the privilege to act as an agent of the Soviet State, meaning he accepted, even embraced his status as a loser, a real-life Doctor Zhivago. Who died in the Gulag after miraculously surviving for years, writing a poem against Stalin without breaking stride, “a gesture, an act that flowed logically from the whole of his life and work.”10

Give us all the courage to be losers. Give us the grace to be artists.

Hannah Arendt, “Ideology and Terror, A New Form of Government,” Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1966), p. 493.

Augustine, Soliloquies II, 10, 18; trans T.F. Gilligan, Fathers of the Church, vol. 44. New York: Cima Publishing, 1948), 401-402; see also Paul Ricœur, « Préface », in Hannah Arendt, Condition de l’homme moderne (Paris : Presse Pocket, 1988), pp. 11-15; Immanuel Kant, “Introduction,” Critique of Pure Reason [Kritik der Reinen Vernunft, 1781].

cf. “White Man’s Buren,” WOID XXII-39, note 5.

Patrick Ravignant, L'Odéon est ouvert [La Prise de l'Odéon] (Paris: Stock, 1968), pp. 54, 62, 140.

Rijin Sahakian, “Beyond Repair. Regarding Torture at the Berlin Biennale,” Artforum (July 29, 2022); https://www.artforum.com/slant/regarding-torture-at-the-berlin-biennale-88836

Paul Werner, “Technoshoah,“ WOID xxi-19 (October 11-12, 2019). http://theorangepress.com/entfern/woidxxi19.html ‘ BDM: “Bund Deutscher Mädel,“ “League of German Maidens,” a Nazi organisation for young women; also: a Goody Two-Shoes; also: “Business Development Manager.”

Robert Jay Lifton, “Preface,” in Alexander and Margarete Mitscherlich, The Inability to Mourn: Principles of Collective Behaviour (New York: Grove Press, 1975) p. xix.

Clarence Brown, "Introduction," in Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope against Hope. A Memoir. (New York: Athenaeum, 1970), p. x.

Mitscherlich, op. cit., p. 25.

Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope against Hope, p. 165.