Review: The Patriot O’Flaherty’s NYC 55 Ave C July 14th through August 9th, 2022

I don’t know if The Patriot will go down with Les Indépendants, Les Incohérents, Le Salon des Refusés or the Ausstellung der Entarteten »Kunst«, the exhibition of “Decadent” art set up by the Nazis as a public humiliation for the artists involved. All I know is, The Patriot has gone down already, having closed August 9 along with the gallery that hosted it. The lease ran out.

You could say The Patriot went down fighting, but what kind of a fight? When a show like The Patriot tries for something new and daring, an aesthetic last hurrah, you can be sure it’s something new and daring that’s been done before. “Everything,” said Paul Valéry, “changes, except the avant-garde.”

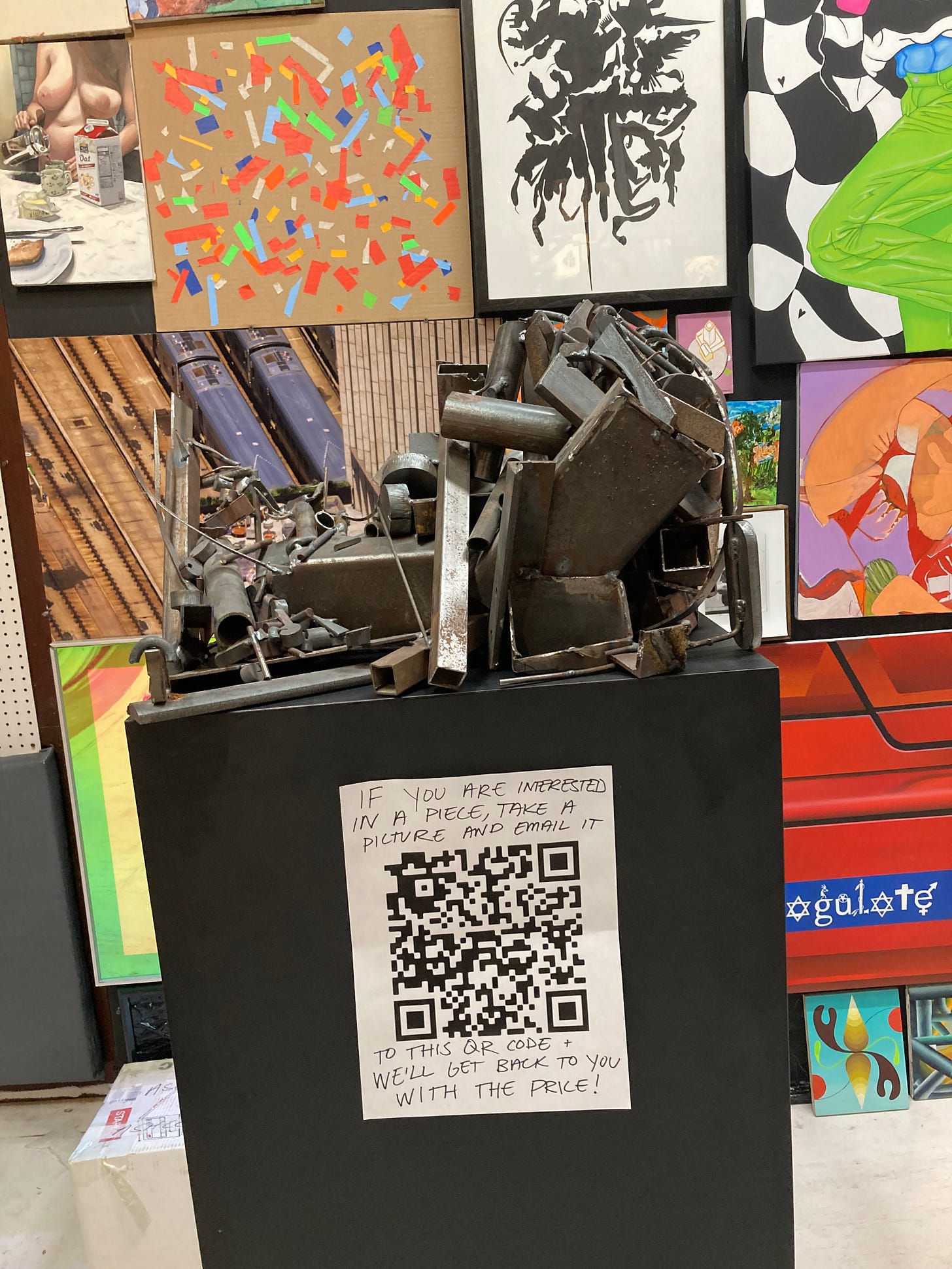

“The Patriot is a truly democratic show where everyone is treated like shit,” says the gallery flyer. But I can’t tell if it’s a flyer or an invitation; it it’s aimed at the artists, or the public, or if it simply confuses one and the other:

An open call where anybody who turns up can show their work would make The Patriot a version of the Salon des Refusés in 1863, when artists turned down by the jury for the State-sponsored Salon were given a separate venue. This is where Manet first showed Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe and Whistler, Symphony in White #1 and both were “treated like shit.” Except the artists on show were treated like shit by the public, mostly, and not by the artists themselves, or the exhibitor, who was pretty much content to let the public and the artists decide for themselves. For the gallerists at O’Flaherty’s the humiliation is that it’s summer and “the rich people are out of town.” If a work of art’s shown and there’s no rich folks to see it, does it cease to be art? Does its public cease to be a public and the artists, artists?

And if crowds of people turn up for the opening, does that make the art not art, and the public not a public, or is it the wrong kind of art and the wrong kind of public, or failed art and a public failure? The original idea behind O’Flaherty’s was that gallery-going is just another form of barhopping, hence the gallery’s name. As the head of the local Community Board’s Liquor Licenses Committee used to say, if you have to serve cheap liquor to get people in the door then the art must be pretty bad to begin with.

That’s pretty much how the critic for the New York Times saw the opening, noting that the Police had to send “at least a dozen officers and several patrol cars.”1 His point of reference was not the Refusés but the Stonewall Riots, when the Police, who til then had been perfectly satisfied with public partying, decided this particular type of party-goer was not acceptable. The critic leaves no doubt that the participants, “many of them… waiting to see their own work,” were some kind of degenerate: “an unclassifiable and, frankly, deranged group exhibition;” “not polite;” “rabid excess;” “hysterical, profane, unsanitary, obnoxious and vaguely disquieting.” Also “desperate for exposure and recognition” as well as “clamoring for exposure and desperate for recognition.” The adjectives applied to failed artists are the ones once applied to failed heterosexuals and failed White Folks. And the critic adds, “It’s also a lot of fun.” Those people know how to party.

In the end the “Exhibition of Degenerate ‘Art’” may be the best point of reference. Like The Patriot , the Nazi exhibition of “Degenerate” Art had paintings haphazardly hung or stacked on the floor, a visual equivalent of “Democratic… precepts” designed to destroy social hierarchies through “carefully planned decomposing activities:” “a bar-room mystique.”2 In other terms “a truly democratic show where everyone is treated equally like shit.” The Nazis were disappointed when their spies reported that the average German was actually enjoying the art: the public was siding with the artists against the gallery. Likewise a lot of visitors, clearly, were enjoying the artwork on Avenue C; I was one of them. Not that I care to rate the art, just that the experience was so much more enjoyable than so many recent shows. “Fun,” you might say.

The late art historian and critic Leo Steinberg argued that, when you’re confronted with art that triggers a reaction you did not anticipate, you have a responsibility to ask yourself whether you yourself need to develop “Other Criteria” in your own practice. This, he argued, was a social, not an aesthetic imperative, requiring first of all a rejection of the “interdictory stance—the attitude that tells an artist what he ought not to do, and the spectator what he ought not to see.”3 You can’t theorize something into being Beautiful out of thin air, that’s the justification of all theories of Beauty; but you can identify emerging or re-emerging forms of sensibility, and this was one such form.

The critic for the New York Times got it exactly wrong:

“If the overall effect is that of a Cooper Union thesis show on psilocybin, it exposes, probably inadvertently, the deep and teeming desire among the city’s artists clamoring for exposure and desperate for recognition, and the difficulty in securing commissions and representation.”

Quite the opposite. This show set itself apart by its rejection of the fear of failure—their own, your own, my own. For as long as I’ve lived I’ve been told not to trust the taste of the many; but what about the crushing taste of the few? I still see in memory a highly respected, well-known art critic close to tears because Agnes Gund, the all-powerful museum trustee, had peremptorily told him such-and-such an artist was simply not, my dear.

Back in 1787, in the years leading up to the Revolution, a French critic got it right:

“The applause of a single class all too often leaves flaws enshrined: as long as the same grandees are seen in the same seats at the theater you can expect to see the same depravity onstage.”

« Les applaudissements d’une seule classe consacrent trop souvent des défauts: tant qu’aux mêmes loges on verra les mêmes Grands, on doit s’attendre à voir sur la Scène les mêmes vices. »4

It’s a sad situation when the thing most needed if you want to make art, is not to suck up to the rich. Or perhaps that’s cause for hope.

Art that’s not about the money? That would be some revolution, comrades.

Max Lakin, “Divine Excess on Avenue C.” New York Times, July 20, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/20/arts/design/oflahertys-gallery-east-village-art-party.html

Alfred Rosenberg, “The Myth of the Twentieth Century.” from Alfred Rosenberg, Selected Writings, quoted Art in Theory 1900-2000. An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison & Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), p. 413.

Leo Steinberg, "Other Criteria." Other Criteria, Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art (London: Oxford University Press, 1972), p. 64.

Anonymous [Louis-François-Henri Lefébure]. Encore un coup de patte, pour le dernier, ou Dialogue sur le Salon de 1787. Première partie (Paris: [n. p.], 1787, p. 4; see “Genius of Revolution,” WOID XXII-36 ; “The Thomas Crow Affair,” WOID XXII-35.