part I of IV

“The friends of Truth are those who seek, not those who boast of having found it.”

« Les amis de la Vérité sont ceux qui la cherchent et non ceux qui se vantent de l'avoir trouvée. » — Marquis de Condorcet, victim of the Great Terror.

In The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. Du Bois tells how an urbane Black man buys a ticket to Wagner’s Parsifal. (He happens to like Wagner. Go figure.) Shortly into the Overture an usher comes over to suggest that, while he has every right to be there, he should consider that the other patrons, too, are entitled to the peaceful and stress-free enjoyment of a Blackless concert, and leave.1

Today the same request, in Florida and elsewhere, is directed at teachers, faculty or, for that matter, museum lecturers. Teachers, faculty, educators and others are banned from teaching anything that makes an individual “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin.”2 White folks are entitled to Blackless History. And blackless concerts. And blackless lives. Because all that blackness makes them feel uncomfortable.

The difference today is, the one who’s telling you to leave is a made opinion columnist at the New York Times and an associate professor of linguistics at Columbia. Also, Black. His name is John McWhorter—actually John Hamilton McWhorter V. When someone a Columbia professor sets out to popularize an expression in the pages of the New York Times you’d think he’d have researched its common use. When a cunning little linguist like McWhorter manipulates the meaning of an expression in common use you can be sure he’s trying to substitute another, synthetic meaning for the current one, hoping it will lurch into the world, a Frankenstein delusion of linguistic omnipotence. Delusions of omnipotence are to The New York Times what gasoline is to a ’76 Pontiac: it's what keeps the junkheap running.

The expression is standpoint epistemology, and McWhorter brings it up in his defense of the State of Florida’s suppression of what McWhorter takes to be Black Studies. Doubtless McWhorter hopes the expression standpoint epistemology has a future. But the expression has a past that’s nothing like what he’s after.

The concept of standpoint has been used in Social Work for decades. A Black household, for instance, may distribute parenting roles in ways different from a White household, and the researcher or social worker needs to be aware of those differences. Occasionally the word epistemology is tacked on to suggest that divergent ways of thinking (as well as social practices) may be anchored in subjective experience. It’s a current of thought that runs from Montaigne to Pascal to Marx to Wittgenstein and, arguably, to certain aspects of postmodernist thought: epistemologies, our ways of apprehending the world, come from experience, not from induction. So it takes a certain type of malice mixed with arrogance to dismiss all this, as McWhorter does, with a simple epithet:

“To pretend that where Blackness is concerned, certain views must be treated as truth despite intelligent and sustained critique is to give in to the illogic of standpoint epistemology: ‘That which rubs me the wrong way is indisputably immoral’.”3

McWhorter’s educational philosophy is eerily similar to that of Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne, a close associate of Robespierre and inspired architect of Terror. Here is Billaud-Varenne discussing before the French National Assembly “those simple truths that constitute the elements of happiness in society” (« ces vérités simples qui forment les éléments du bonheur social. »):

“Vices are like poisonous plants: they must be sought expressly to be found; whereas the healthy, life-giving productions bloom everywhere beneath our steps.”

« Les vices sont comme les plantes vénéneuses : il faut les chercher exprès pour en trouver ; au lieu que les productions salutaires et vivifiantes croissent de tous côtés sous nos pas. »4

For McWhorter as for Billaud-Varenne, truth is intuitive. Both reject whole areas of logical practice as willful lies, not untrue as a matter of record but deliberately so, a matter of will. A counter-statement is not a logical proposition (“this is not true“) but a moral failing, a vice. Like most French and German academics, and a number of Americans, McWhorter follows in the footsteps of Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher who, with some help from Billaud-Varenne and other contemporaries, laid out the philosophical foundations of Intellectual Terror in the Modern Age:

“Therefore, true morality can only be based on principles: the more general they are, the more sublime and noble they become. These principles are not speculative rules, but the consciousness of a feeling that lies in every human heart, one that extends much farther than any particular motive of sympathy or affection. I believe I connect all things when I say it is the Sense of Beauty, and of the Dignity of Human Nature.”5

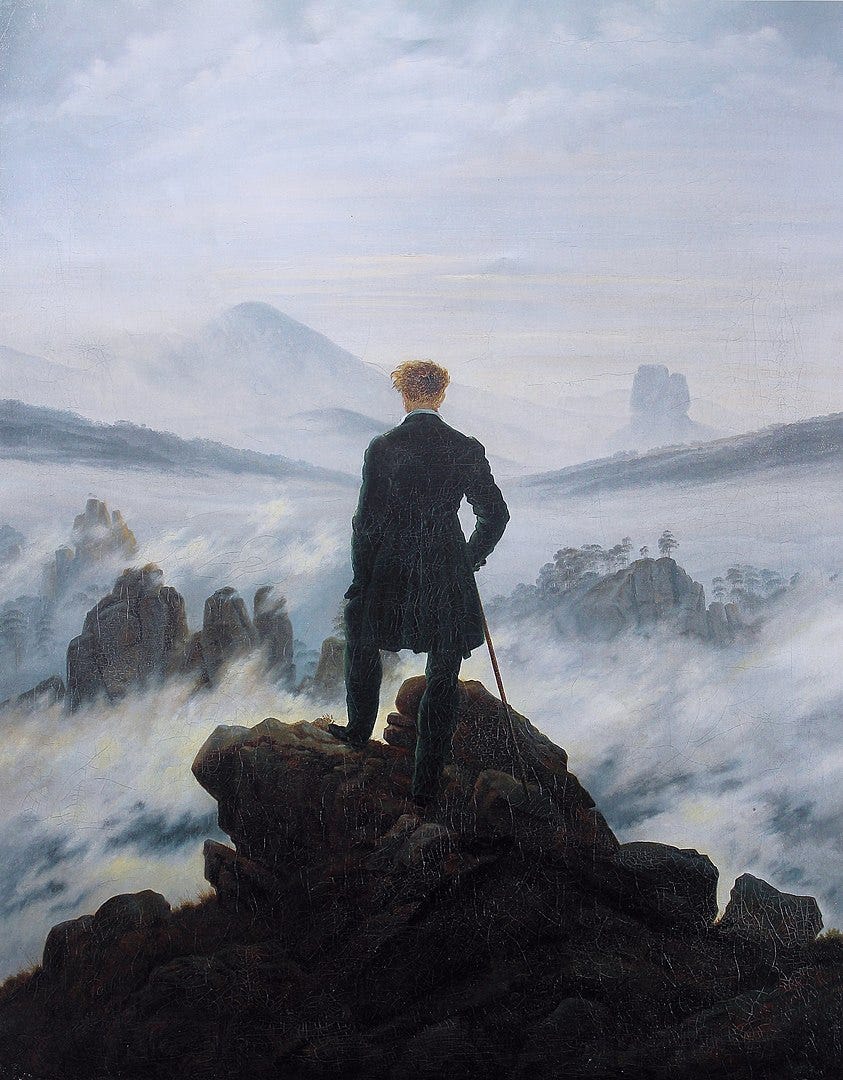

For Kant, moral action is no longer relative to an individual’s position in society; it becomes an essential category, intuitively apprehended, transcending sense experience, accessible to the chosen.

And this is what Kant calls the Sublime [das Erhabene].

Some day I will patent a Fascometer, an instrument that measures how soon a speaker comes to claim absolute, intuitive authority as a function of their progressive inability to pursue an argument by rational means. By that standard Billaud-Varenne ranks high. So does McWhorter.

part II of IV:

WOID XXIII-10a1. 1/4.

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk [1903] Writings (New York: Library of America, 1986), p. 527.

Florida Statutes, Section 760.10: "Unlawful Employment Practices," (8), 7, as revised, Florida House of Representatives HB7 2022 “Stop Woke Act.” https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2022/7/BillText/Filed/PDF.

John McWhorter, “DeSantis May Have Been Right,” New York Times (February 16, 2023). https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/16/opinion/desantis-may-have-been-right.html. Cf. Zora Neale Hurston, “The ‘Pet Negro’ System,” You Don't Know us Negroes and other Essays (New York, NY : Harper Collins Publishers, 2022), pp. 234-235.

Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne, « Rapport, présenté par Billaud-Varenne au nom du comité de salut public, sur la guerre et les moyens de la soutenir, lors de la séance du 1er floréal an II (20 avril 1794) » in Réimpression de l’Ancien Moniteur, 1847-1850 (vol. 20, no. 212): p. 267.

Immanuel Kant, Beobachtungen über das Gefühl des Schönen und Erhabenen (Königsberg : Johann Jacob Kanter, 1766), p. 23; see also Ferdinand Alquié, « Introduction », Emmanuel Kant. Oeuvres philosophiques. I. Des premiers écrits à la Critique de la raison pure (Paris : Gallimard, 1980), p. 441; Jan Ellen Goldstein, The Post-revolutionary Self. Politics and Psyche in France, 1750-1850 (Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press, 2005).