Pompeii in Color. The Life of Roman Painting.

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

Through May 29, 2022

Tues-Sun, 11am-6pm

Friday 11am-8pm

Closed Mondays

The question that needs to be asked about the Classical story of birds pecking at a painting of grapes isn’t the failure or success of representation, but its purpose.

I]

There’s an old academic paper addressing the experience of the Master of the Beads of Condensation on a Bottle of Beer. The Master is a commercial artist desperate to use his talents in a real challenge. Unfortunately, his reputation rests on his skill at painting drops of condensation on a bottle of beer. No doubt if he wasn’t so prized he might achieve great things: images of babes tossing volleyballs on a beach, or children in pigtails eating waffles, like a real artist does, but his bottle-of-beer skills are what defines him, at least to those for whom the ability to show beads of condensation is the Summum Bonum and the beans to boot.

I get the same feeling from Pompeii in Color. The show displays some 35 frescoes and attendant objects from the National Archeological Museum of Naples. Most were collected early on, before it was grasped that works of art — especially these — are best understood in the locations where they were first seen and painted. (That would be before 1796, when Quatremère de Quincy published his Letters on the prejudice to the arts and science caused by the removal of the artistic monuments of Italy. (Lettres sur le préjudice qu'occasionneroient aux arts et à la science, le déplacement des monumens de l'art de l'Italie etc.) Since so much of what these works had to say and say to us today hangs on their placement in space this show is a poor substitute for the experience of Pompeii itself. (My advice: rather than a day-trip from Naples, stay overnight in the town of Pompeii itself and approach the digs from the back entrance, which is less crowded.)

The next best approach would be a close phenomenological reading of the works on display here: what is it about them that makes their placement in space (or rather the painter’s conscious relationship to the concept of placement in space) so pregnant for artists and designers today? These are works not merely conscious of spatial relations but consciously about space, and it’s a consciousness shared by those artists who rediscovered them in the eighteenth century, when they were first unearthed.

The third option, that of the curators of Pompeii in Color, is to put these works in some kind of historic or social context. There are bowls of dried paints on display, left by the painters as they fled the eruption of Vesuvius, hence the House of the Painters at Work, not to be confused with the House of Punished Love, though the confusion would be forgivable if you were an artist. Here labels are useless, if not outright misleading: rose madder, a pigment?

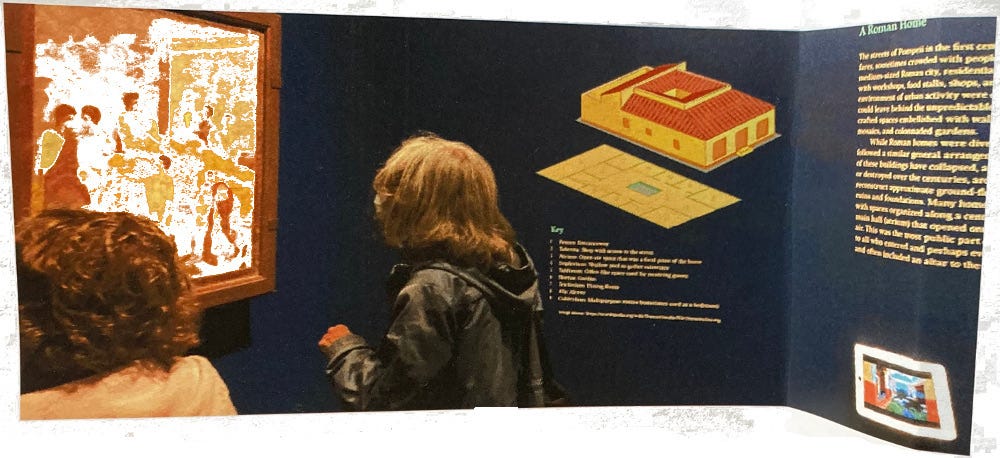

Then there is a diagram of a typical house, with information about the various rooms, their uses, and a suggestion that the theme of a fresco would depend on the uses ascribed to each area. There is a cautious admission that “Enslaved people likely moved through all spaces […] but evidence of how they understood the images is extremely rare and indirect.” All très woke, my dear, but as usual the experience of un-slaves is taken to be the norm, not one out of several experiences competing and converging on the surface of a painting. Chances are, the slaves understood these images as well, or not better, than the masters since the artists were most likely slaves themselves. Consider these frescoes as the social equivalent of inscriptions on Pompeiian walls, except that the writings I’ve seen there have fewer superimposed or contradictory agendas.

These superimposed agendas are gingerly tackled in the signage for the show:

“Some paintings display similar compositional patterns, suggesting that their creators were following artistic precedents or fashions. Other paintings seem more idiosyncratic, perhaps an expression of an artisan’s creativity or a reflection of the personal tastes of a patron.”

Creativity seems too strong a word. All of the works on display are hack work: competent, but cold as fish. Kind of like wall scribblings, minus the sarcasm. Considering that a slave, by Aristotle’s definition, was a purely mechanical instrument, the idea of an artisan thinking, let alone feeling, must have seemed ludicrous at the time, like the idea that the guy who paints the condensation on a beer bottle has the potential to become a “real” artist.

II]

Pliny the Elder, who himself had an unfortunate connection with Pompeii, had his own idea of what constituted the Summum Bonum in Art, and it was pretty much the same as the Master of the Beads or, perhaps, the organizers of this show:

“To give the contour of the figures, and make a satisfactory boundary where the painting within finishes, is rarely attained in successful artistry. For the contour ought to round itself off and so terminate as to suggest the presence of other parts behind it also, and disclose even what it hides.” 1

The passage in Pliny immediately preceding this one suggests that true artistry consists in sacrificing the technical parts to the idealized whole, a practical application of Plato’s argument (in Book X of The Republic) that “real” art is the idea of the whole, not the accumulation of the constituent parts. From that point of view the works in this show would be miserable failures. There is nothing here to make your heart skip a beat: it’s all technical minutiae, beads of condensation, ill-fitting parts. Narratives are never more than an awkward assemblage of fragments: the placement of a generic symbol on a generic head, an attempt to interlock passe-partout figures, the assemblage of rote gestures and images. Literary allusions are less present than in the wall inscriptions themselves. Most obvious, and of most interest to artists now: conflicting perspectival systems crowd one another out, the organization of space attempting to present itself as an organization in space.

As Jacques Lacan pointed out, the question that’s begged by the Classical story of birds pecking at a painting of grapes isn’t the failure or success of representation, but its purpose. 2 That was, into the Byzantine era, the meaning of the word “Perspective:” not the presentation of the world but the organizational system by which the meaning of the world is made perceptible to the viewer. The curators of Pompeii in Color speak of “carefully crafted spaces,” but not of the crafting of the concept of space, or the purpose of this particular craft, which is unusual since traditional typologies of Roman wall paintings use these concepts to distinguish the major stylistics trends. Whether these concepts are to be placed in any kind of social hierarchy or chronology, even, is another matter. Now or then we have no reason to believe that a fully formed picture (of virgines playing volleyball, for instance), is in any way superior to the beads on an amphora.

Jacques Louis David once commented that all those works ripped from their environment might some day bring forth a Winckelmann, but no artists; he was referring to the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s influential idea that art merely reflected the harmony of the surrounding social environment, counterposing the observation that artists could never escape the pressures of their own historical conjuncture simply by painting what they could never experience themselves.3 Here the focus must shift from “those who used these rooms” to “those who were used by them” as axis of our understanding. Once John Ford the movie director was blocking out a scene with John Wayne the actor. All of a sudden John Wayne stopped and said,

“John, what’s my motivation?” “Uh?” “Like, what am I supposed to be thinking?” “John. You push open the saloon doors. You stand where the X is marked on the floor. You say, ‘Dirty Deke, I’ve come to take you in.’ But whatever you do, don’t think."

Did the artist-slaves of Pompeii aspire likewise to be “real” artists? Only in the manner that the Master of the Beads of Condensation aspired to the same mythical status. the Master’s situation is not improved by transferring the object of his desires to a higher, nobler, and entirely mythical level, but by grasping the limitations of his sysyphean task in the here-and-now.

Original publication date: May 22, 2022; revised May 25.

Historia Naturalis XXXV.xxxvi.67-68; transl. H. Rackham in Pliny. Natural History, IX (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968), 311.

Jacques Lacan. « Qu'est-ce qu'un tableau? » Le séminaire. Livre XI. Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller (Paris: Le Seuil, 1975), 102.

Etienne-Jean Delécluze, David. Son école & son temps (Paris: Didier 1855), 209; similar argument in Karl Marx, Introduction to the Grundrisse. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/ch01.htm#loc4