Review: Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina

Metropolitan Museum of Art, through February 5, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2022/edgefield

Catalog: Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, ed. Adrienne Spinozzi. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

I]

I’ve heard this more than once from the younger of my Black students: I present them with a positive image of a Black in the past, say an Ancient Egyptian functionary, and they cheerfully announce, “That one’s a slave.” That’s not too far from Hear Me Now, an exhibition of ceramics made by enslaved Black potters in the years before the Civil War, except my students are in on their own joke and the curators, not.

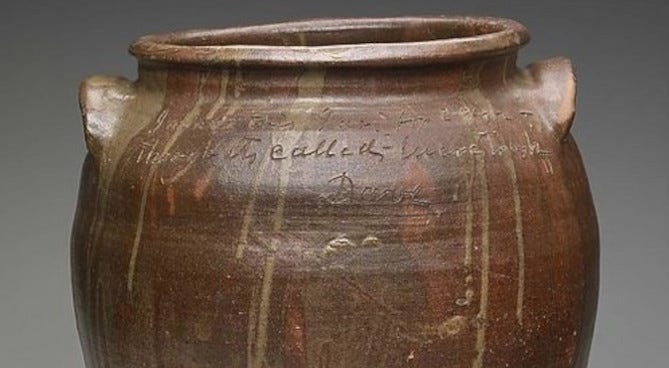

It’s a moving show. The works, with their molasses glazes, have a forged-in-fire feel. For context there are similar works by local Native American potters and more recent works by African American artists. And of course, the striking and mysterious heads of Black men. It’s the scholarship that gets in the way, or lack thereof. One object in particular, a large storage jar, is so silenced that it demands interpretation. “That one’s a slave” won’t do it.

This particular jar was crafted in 1857, one of several by the artist known as “Dave,” full name David Drake (1801–1870s). The signage is mostly silent about certain features of this work, leaving it so far outside the narrative as to challenge the narrative itself. “Dave” signed his work, which suggests he could write well enough to sign his name. Also, he wrote short sentences and rhymes on any number of pots, in a cursive, yet, and with adequate spelling. Dave, one may conclude, could read and write fluently, and this runs against the common assumption that slaves were not allowed to do either. Many slaves had useful skills like carpentry or pottery-making or cooking, perhaps other skills that required some form of literacy. Dave himself was a skilled craftsman and that makes him more than a slave, or maybe just a slave of a different kind to a different kind of master.

II]

In an oft-quoted summing up, the preeminent scholar of Jewish History Salo Baron wrote:

“All my life I have been struggling against the hitherto dominant ‘lachrymose conception of Jewish history’ [...] because I have felt that, by exclusively overemphasizing Jewish sufferings, it distorted the total picture of the Jewish historic evolution and, at the same time, it served badly a generation which had become impatient with the ‘nightmare’ of endless persecutions and massacres.”

This is what my students were trying to convey: they, too, felt poorly served by a narrative that reduced the Black experience to an endless, claustrophobic nightmare in which Blacks, like Jews, were the passive objects of historical forces, not the subjects of their own destiny. This explains why the myth of the all-powerful Jews is the most common form of Black antisemitism: the Jews as hoarders of agency. Baron adds:

"A proper understanding of Jewish history presupposes the close interchange of external and internal factors. One could indeed suggest that all Jewish history, particularly during the last two millennia of the dispersion, was essentially the resultant of conflicting internal and external pressures.”1

If the experience of the oppressed is to be correctly understood, it must be understood not merely as a story of victimhood, but as a story of complex interactions with the wider circle of accomplices and allies and others. All too often in Academia, calls for inclusiveness and complaints of cultural appropriation reduce themselves to petty turf wars between disciplines and departments, each, as Zola put it, a dog growling over his bone to keep the other dogs at bay. Likewise, in their eagerness to fence in what they wish to consider unique to the African American experience, the curators have excluded that which connects the experience, the object, or the artist himself with the dominant culture that surrounds and defines him and with which he, too, perforce, must actively engage. The catalog is heavy on the lachrymose, clear on facts, and very light on interpretation.

III]

One indicator of Dave’s engagement with the world around him is a storage jar on loan from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts [Harriet Otis Cruft Fund and Otis Norcross Fund (1997.10)], bearing an incised inscription:

"Lm Aug. 22, 1857 / Dave"

And on the opposite side,

"I made this Jar for Cash- / though its called lucre trash / Dave"

It was not uncommon for skilled slave to be hired out to other “masters,” though this was more common in urban settings further North along the Atlantic Seaboard, where the economy could sustain their regular use. Edgefield is just outside the border with Georgia, a few miles North of Hell in other terms, and one gets the sense this payment was unusual. Dave at any rate was paid directly for his work, which was not the usual practice as far as he himself thought about it. This may explain why he drew attention to the fact, but it does not explain his own sentiments about the procedure. As any sociologist will tell you if his name happens to be Pierre Bourdieu, individuals can only react to a new social situation with the vocabulary and concepts available to them at that time; Marx would have added that “In any given epoch the ruling ideas are the ideas of the ruling class,” and those are the ideas that Dave reached for.

Nineteen-fifty-seven is also the year George Fitzhugh published his best-known work, Cannibals All! Or, Slaves without Masters, a pretend poised and superficially sophisticated defense of slavery, the kind of thing you’d expect from David Brooks today if Brooks hadn’t moved on to LGBTQ. It would be worthwhile seeking out what month the book was published, and what was its local resonance. No matter: Cannibals All! followed a previous apologetics by the same author, Sociology for the South (1854), whose argument is close to whatever Dave might have picked up at first or second hand. Fitzhugh was only one of many intellectual apologists for slavery in the antebellum South, and like others he borrowed from British reactionary intellectuals to argue that free-market capitalism had destroyed the social fabric by abolishing the bonds of loyalty, precedence and, yes, serfdom, that had kept us all happy and as one. Fitzhugh was popular with Southern readers, and for the same reason, hugely unpopular in the North. The half-title of his first book gives an indication why: Or the Failure of Free Society. Fitzhugh’s originality lies in his fresh suggestion that the free market and slavery are similar systems of exploitation. No doubt some would agree with Fitzhugh that to call free labor wage slavery as the socialists did was "a gross libel,” except Fitzhugh, in typical White supremacist fashion, thought it was slavery, not the free-market economy, that was libeled.2 Fitzhugh was familiar with Socialist theory and had most likely read the Communist Manifesto. Marx’s groundbreaking manuscript for the Grundrisse was written the same year Cannibals All! was published: the same year Dave’s pot was thrown. This is the context within which we must read Dave’s denunciation of “Lucre”— what Fitzhugh, borrowing from the reactionary socialist Thomas Carlyle, called “Mammonism.”

We now begin to grasp the curators’ discomfort: is Dave channeling Fitzhugh’s pro-slavery position or his opposition to the free market? The real challenge lies in distinguishing the two. As stated by C. Vann Woodward, the preeminent historian of Jim Crow (and that stuffy White guy seen marching next to his friend Martin Luther King in the photographs),

“Granting all his doctrine to be quite un-American, one might still ask that Fitzhugh's thought be re-examined, if only for the sharp relief in which it throws the habitual lineaments of the American mind.”3

IV]

For those habitual lineaments we turn to Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain’s speech to the mutineers in the 1993 movie, Gettysburg, feelingly interpreted by the actor Jeff Daniels (This clip is included in the Army ROTC curriculum):

“Whether you fight or not, that's — that's up to you. […] All of us volunteered to fight for the union, just as you did. […] We are an army out to set other men free. America should be free ground — all of it. […] So if you choose to join us, I’ll be personally very grateful.”4

The unspoken irony is: the mutineers have enlisted. They’ve chosen voluntary servitude to abolish involuntary servitude. Now they’ve been given a choice, either volunteer to get themselves shot, or volunteer to be court-martialed and shot. Likewise, in a free-market economy you may voluntarily choose to get a job (which African Americans call a “slave”), or volunteer to starve. There is no contradiction in saying that the “War to Free the Slaves” was at once a conflict to abolish slavery and to preserve wage slavery, two sides of the same coin. The expression “involuntary servitude” would be a redundancy if it weren’t implicitly contrasted with voluntary servitude.

On that basis it would be misleading to argue that the mutineers and soldiers stand apart from the struggles of enslaved people, or that Dave, in criticizing Mammon, does the same. On reflection, it’s the opposite: it’s because they have a share, in whatever small degree, in the same condition, that we can empathize with all. And I turn to my students, and in my mind I answer: “Of course he’s a slave. We’re all slaves to one degree or another, and that’s what makes us brothers.”

Salo Baron, “Newer Emphases in Jewish History.” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Oct., 1963), p. 240, 244.

George Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South Or the Failure of Free Society (Richmond, VA: A. Morris, 1854), p. 251; Cannibals All! Or, Slaves without Masters. Richmond, VA: A. Morris, 1857.

C. Vann Woodward, “George Fitzhugh, Sui Generi,” Cannibals all! or, Slaves without masters, ed. C. Vann Woodward (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1960), ix.

Ron Maxwell (Director), Gettysburg (Film), 1993. New Line Cinema.

In L'Esprit des Lois, the grand-daddy of political theory, Montesquieu puts Voluntary and Involuntary Servitude in one general category.