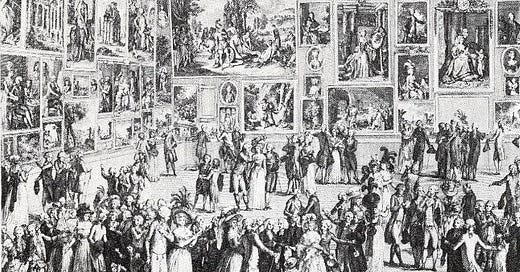

There are times when the talk about the art is more interesting than the art itself, for instance in the ‘eighties and ‘nineties, when all kinds of fancy-pants theories were poured into the paper cup of art. Or the years leading up to the French Revolution, when art criticism was a corrosive attack on the Royal System on par with Philosophy and Pornography, and artists struggled to keep up. The biennial Salon, a critic wrote, “feels like witnessing a public celebration attended by all citizens.”1 These gatherings were swamped with cheap pamphlets, what the French call Nouvelles sous le manteau, the kind of writing a shady character pulls out from under his cloak. Many were written by that underclass of over-educated, underpaid writers that would eventually rise in revolution. Even Jean-Paul Marat, the future leader, tried his hand at art criticism. Long before getting stabbed, Marat did a little stabbing of his own.

It's easy to misread these pamphlets; you need a solid background in the philosophical debates of the day, those being times when a philosophe was a critic of the state of things, not an apologist. Or perhaps those writings, like the revolutionary process itself, bide their time in darkness until they begin to make sense to us, “a memory [that] flashes up at a moment of danger.” [Walter Benjamin.]

That’s how one critic saw matters in 1789, the year the Revolution broke out:

“I know that Art never shines as brightly as after the great revolutions of empires. I know explosions of courage are followed by explosions of talent among all peoples; but I hazard, that as revolutions help to develop great feelings among artists, so, too, those revolutions have been prepared by the great feelings of the artists themselves. Genius seems to go with freedom only after it has truly laid out everything for its triumph.

The times in which we live may serve some day to answer this intriguing question.”

« Je sais que les Arts n'ont jamais éclaté d'avantage qu'après les grandes révolutions des Empires. Je sais qu'à l'explosion du courage on voit chez tous les peuples succéder une explosion de talents ; mais j'ose soutenir que si les révolutions contribuent à développer de grands sentiments dans les Artistes, ce sont les grands sentiments des Artistes eux-mêmes, qui ont préparé ces révolutions, et qu'ainsi le génie ne paraît accompagner la liberté qu'après avoir très-réellement disposé tout pour son triomphe.

L’époque où nous nous trouvons peut servir un jour à décider cette intéressante question. »2

This passage is a riff on Denis Diderot’s writings on the topic of Genius, notably De la poésie dramatique [1758] and his entry for that foundational source of Enlightenment fervor, the Encyclopédie [1757]. It’s a suitable epigraph for a groundbreaking article by Thomas Crow, who built his reputation on a thoroughly researched overview of the role of art criticism in the run-up to the French Revolution.3 The quote seems made to order for Crow’s major interest, the focus for anyone interested in the Art of the French Revolution: Jacques Louis David. Never mind that the critic doesn’t quite mean genius in the modern sense of an individual who makes History by transcending it, an “unacknowledged legislator of the world.” Nor does the word “génie” carry that sense of rampant individualism that’s become a prerequisite for all claims of artistic worth in the twentieth century, especially claims of revolutionary leadership in the Arts. In the eighteenth century the word refers to intuition and spontaneity, qualities the critic himself finds lacking in David. Crow, then, is working from an understanding of the role of artists worthy of his own time and not of theirs. A few months ago in the central atrium of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, I noted a giant screen on which an artist was seen talking endlessly and soundlessly. The experience was like Big Brother, except that the artist in question was a Person Of Color. That’s not what the Revolution wanted to be about in 1789.

To top it all off, Crow adds a second epigraph so divergent, contradictory even, that one wonders how the two fit. Crow claims both statements are from the same author, the playright and factotum Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle. The 1789 passage is most likely not his; the pamphlet of 1785, most likely is:

“Suppose one were to say to this small number of men who own everything, ‘Keep the artists busy and pay them well: for with only the smallest fraction of that same skill [génie] with which they bring marble and canvas to life they might, should they wish, find a sure means to enrich himself at your expense.’ No doubt this proposal, if they considered it well, would make them less exacting, financially.”

“Would this million men or so, who speak so complacently of their vast estates, believe them to rest on solid foundations if twenty-four million others were to stop receiving from them a fair and regular wage for their industry?

« Si l’on disoit à ce petit nombre d’hommes qui possèdent tout, occupez l’Artiste : & payez-le bien ; car avec la moindre parcelle de ce même génie dont il anime le marbre ou la toile, il pourroit, s’il le vouloit, trouver des moyens sûrs de s’enrichir à vos dépens. Sans doute cette proposition une fois bien méditée, les rendrait moins rigoureux économes.

Ce million d'hommes ou environ, qui parlent avec tant de complaisance de leurs vastes propriétés, les croiroient-ils bien assises, lorsque vingt-quatre millions d'autres hommes cesseraient de retirer de leurs mains le juste & continuel salaire de leur industrie ? » 4

Whatever Carmontelle says here and throughout this pamphlet, is not what Crow would have him say. The critic is attempting to work out a problem in political economy that owes little to theories of Genius and much to Gabriel Bonnot de Mably, the radical writer whose theories lie halfway between those of his friend Rousseau the revolutionary pessimist and his brother Condillac, the proponent of an extreme form of sensationalism in human behavior. Mably’s most enduring argument was the definition of Property as a social construct; his most radical contribution was the belief that communal ownership was logically possible: Property was not a natural right. From Rousseau Mably had borrowed the belief that Society is corrupted by Art, and especially by the luxury arts. Our critic takes the reverse tack, arguing that it’s the production of Art that’s corrupted by its dependency on wealth:

"What is the point of criticizing a product whose flaws belong in some ways less to the person who produces it than to that class of people who buy it?”

« A quoi sert en effet de censurer une production dont les vices appartiennent en quelque sorte moins à celui qui la livre, qu’à la classe des gens qui l’achètent ? » [p. 3.]

At a time when wealth was widely thought to consist in material possessions, the critic interprets art as a form of wealth-making. In a country of twenty-five million, artists have the same social position (the same relations as producers) as twenty-four million others vis-à-vis the 4%. The withholding of artistic labor from those who treat art as capital is interchangeable with the withholding of labor in any form. Dependence on wealth (i.e., on capital) becomes a social, not an individual problem. So much for “genius.”

In the conclusion to this introduction, however, Carmontelle reaches an insight so fitting to our own beliefs that we are left to wonder if we, too, like Crow, are reading what we want to read:

“ May all those whose coffers are full of gold, remember that this metal may suddenly stop standing for wealth. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . and that by hoarding it they instruct the industrious ones to do without entirely by preferring the use of those symbols that replace it.”

« Puissent tous ceux dont les coffres regorgent d’or, se rappeler que ce métal peut cesser tout-à-coup de représenter la richesse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . & que l’enfouir, c’est avertir l’homme industrieux d’apprendre à s’en passer tout-à-fait, en favorisant l’usage des signes qui le remplacent. [p. 12]

As Carmontelle predicted, the French Revolution initiated a massive shift among various systems of symbolic representation, in particular the system for the valuation of those symbolic objects now called Art, as well as the system for the valuation of those symbolic items called Money.5

Yet here’s a revolution still in need of accomplishment: the moment when the two part; when the valuation of Art (or for that matter, the valuation of all labor) breaks free from it valuation in hard, cold cash. To accomplish that revolution, as the critic suggests, is the true definition of artistic genius:

May the true Artists at last indemnify me by their esteem for the wrath of the Artisans.

Puissent enfin les vrais Artistes me dédommager par leur estime du courroux des Artisans. » [p. 12]

The collective task of the artist, then is to break with the cash nexus; those who can’t or won’t are not artists at all, but artisans. “The times in which we live may serve some day to answer this intriguing question.”

I’m looking forward to it.

« On croit assister à une fête populaire, où chaque citoyen va se rendre. » Anonymous [Louis-François-Henri Lefébure], Encore un coup de patte, pour le dernier, ou Dialogue sur le Salon de 1787. Première partie (Paris: [n. p.], 1787), 3.

Anonymous [Louis-François-Henri Lefébure], Vérités agréables ou Le Salon vu en beau, Par l'Auteur du Coup de patte ([Paris :] Chez Knapen & Fils, Imprim. de la Cour des Aides, au bas du Pont Saint Michel 1789), 3 ; quoted Thomas Crow, "The Oath of the Horatii in 1785 : painting and pre-Revolutionary radicalism in France," Art History Vol. 1, no. 4 (1978), 424.

Thomas E. Crow. Painters and public life in eighteenth-century Paris. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Anonymous [Louis Carrogis Carmontelle]. Le Frondeur, ou Dialogues sur le sallon, Par l'Auteur du Coup-de-Patte & du Triumvirat (Paris: [n. p.], 1785), 4-5; quoted Thomas Crow, "The Oath of the Horatii in 1785 : painting and pre-Revolutionary radicalism in France," Art History Vol. 1, no. 4 (1978): 424.

Paul Werner. “Elogio del Vandalismo / In Praise of Vandalism.” Lectio Magistralis, MACRO Asilo – Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome, December 1, 2018. https://www.macroasilo.it/media/paul-werner-elogio-del-vandalismo-000