Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color Through March 26, 2023 Metropolitan Museum of Art

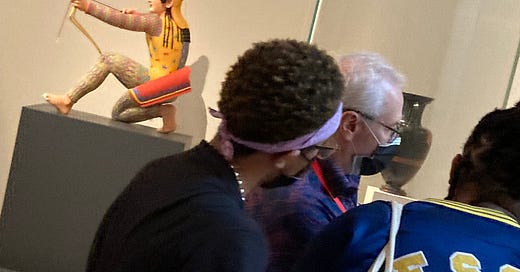

This would happen with heartening frequency. When the time came to cover Egyptian Art in my Survey class I’d show an image of a statue of a Black Egyptian, striding naked as Egyptians showed themselves occasionally, much as the Greeks would later. No doubt I expected a pat on the back. Instead my students — my young male Black students anyhow — would chuckle,

“Hey, you can tell he’s a White guy. Look at the size of his Johnny.”

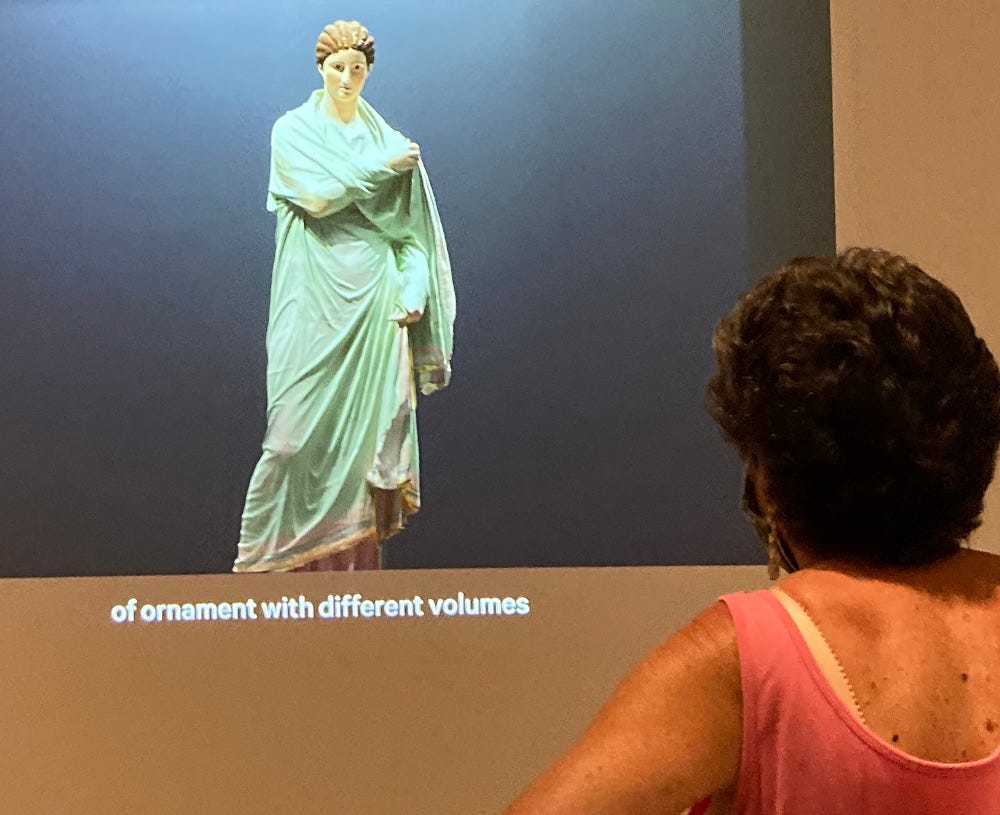

At least I knew I was being baited. I couldn’t say that of the folks at the receiving end of the present exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition whose stated pretension is to restore the look of Classical Greek sculptures As They Really Were. As They Really Were, it turns out, is remarkably like a Jersey housewife plastered with pink makeup. Or a Jeff Koons sculpture, which amounts to the same thing except with Koons there’s an edge of irony that’s entirely missing here. If this is the case for Who the Greeks Really Were, the Met has set the bar pretty low, aesthetically and otherwise. The event reminds me of diva Anna Netrebko defending her own appearances in blackface “arguing that it helps maintain the authenticity of centuries-old works.” Chroma joins Triumph of the Will and your average Metropolitan Opera production: if you think this kind of thing worthwhile there’s something seriously wrong with your aesthetic sense, and your ethics.

Of the ancient Greeks and their culture the German Romantic Friedrich Schiller wrote:

» Sie sind, was wir waren; sie sind, was wir wieder werden sollen. […] Zugleich sind sie Darstellungen unserer höchsten Vollendung im Ideale. « [Über naive und sentimentalische Dichtung, 1795-96.]

“They are what we were; they are what we ought to be again. […] At the same time, they represent our noblest idea of perfection.” [On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry, 1795-96]

Yup. This is what we all hope to be: White folks in pancake makeup. Karl Marx got one of his major insights from Schiller: that economies, cultural or otherwise, were not built around providing satisfaction of natural needs, but around creating the needs to be satisfied, and what’s being created at the Met today is the Need to be White. I can’t say the Black visitors I noticed were terribly impressed. No more than my Black students had been.

It’s only fair to mention Schiller was a major inspiration to the Nazis; that considerable NS effort was expended to make of the Greeks the direct progenitors and inspiration of the Aryan Race—scientifically, of course. Our own need here, as with all of reactionary Science, is not to figure out “What really happened” (Wie es eigentlich geschehen, to quote another proto-Nazi), but the misuses of the past today. The two “scientists” who planned and executed this visual farce are from Germany, World Center of the Expiation Industry. Or, if you prefer your expiation sexy (in a Jersey kind of way) you can let some journo at Hyperallergic go Full Woke Bachant on you. “I shame to wear a heart so white," says Lady Macbeth.

Better, yet, head for the Mezzanine for a salutary corrective: the part where you explain to your students that actually, it’s more complicated than that, and a lot more interesting.

It’s a sweet, understated pushback. The signage here points out that curators and art historians have been delving into painted statuary and architecture for centuries, and the results can be seen in a free-floating group of videos, signage and original artifacts. In a nice little bit of Mean Curator cattiness one panel draws attention to the “nuanced application of pigment” on antique statuary, nuance not being the kind of thing you’ll associate with the OEO kookies on the ground floor.

Nor “application of pigment.” As Martin Bernal pointed out many decades ago, the transition from melanin to its absence in Antiquity was not what the one-drop crowd in America imagines it to be.1 This flexibility is reflected in Greek painting techniques which, as shown here, involve subtle overlapping of different shades of color; reflected as well in the absence of that saturation of baby-doll pink that’s a favorite of racist curators looking to show statuary “as it really was.” Greek artists, like most artists since, understood colors and sculptural materials as a form of mediation, joining divergent types of perception. Bronze, for instance, need not have the deep, dark color we see in most statues, it comes out of the foundry a vulgar gold of the kind only Tony Soprano would love. On the mezzanine a Bronze Statuette of a Black African Youth reminds us of the positive image of the Blackness of Africans in Early Modern Europe, and of their association with the origins of Civilization. Not that the Greeks and Romans weren’t as biased as anyone else, just that they had different ways of registering Otherness or its reverse. Those plastic-surgeon noses get me every time.

And penises, of course. Maybe, I would explain to my students, the tiny-to-them penis was deliberate, not a mere registering of a real pecker but an intentional statement. Small penises: good. Fear of people with large penises? Hey, kids, can you say “apotropaic?”

Because there is something mean-spirited, malicious, about the show downstairs, a passive-aggressive attempt to split the audience under cover of inclusivity. It’s the kind of cheap manipulation you’ve come to expect from German politicians and intellectuals, and from Human Resources everywhere.

“This is the very painting of your fear,” says Lady Macbeth. Please leave me out of it.

July 17, 2022

Martin Bernal. Black Athena. The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987-1991.