Review: Deconstructing Power: W. E. B. Du Bois at the 1900 World’s Fair.

Through May 29, 2023. Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/channel/deconstructing-power/

Admission: $18.00 and down; $2.00 off if you book online. Free from 5:00 to 6:00 pm for working stiffs.

Resources: W. E. B Du Bois. Black lives 1900 : W.E.B. Du Bois at the Paris Exposition, edited by Julian Rothenstein with an introduction by Jacqueline Francis and Stephen G. Hall (London: Redstone Press, 2019) is presently out of stock in the Museum bookstore. Highly recommended. Likewise, the W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (including photographs) are digitized and available online.

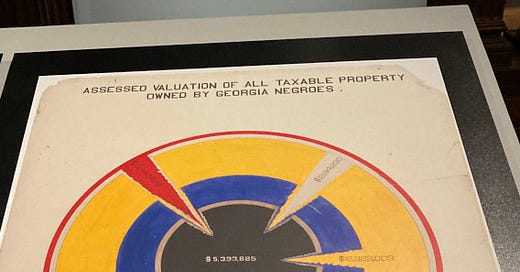

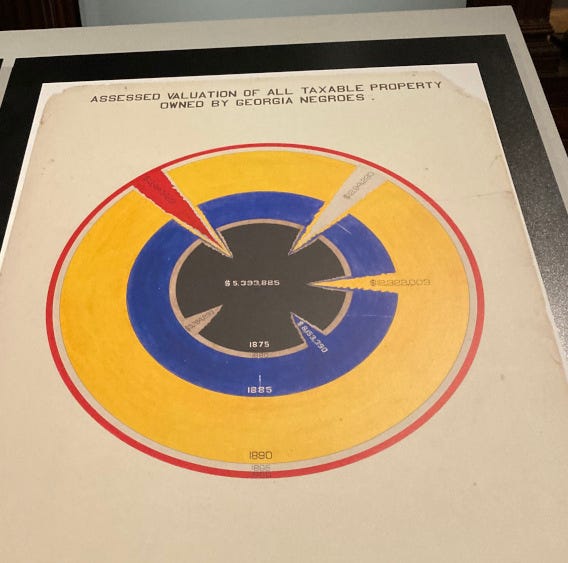

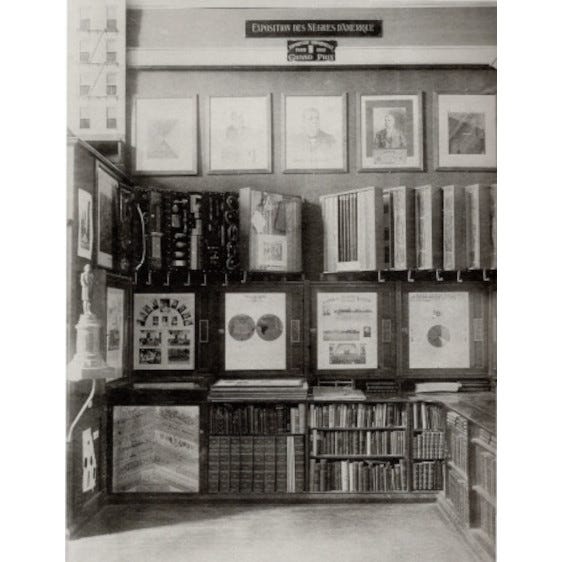

No more excuses. In 1900 the great Black activist and scholar W. E. B. Du Bois organized a presentation at the American Pavilion at the Paris Universal Exposition, with the help of his students at Atlanta University: Exhibit of American Negroes / Exposition des Nègres d’Amérique. It was a small show; in the photographs it looks as though it fit into a closet. It’s even smaller at the Cooper Hewitt Museum in Manhattan. Also narrower in range and spirit.

But it would be hard to overstate the importance of the original show, either for its historical import or for sheer visual elegance. The Exhibit of American Negroes has been included in the College Board’s new curriculum for Advanced Placement in African American Studies. No more excuses.

Except: Excuses. We live in Proposal World, where every kind of cultural event—publication, exhibition, movie — must be preceded by a proposal, circulated behind the scenes to sponsors, publishers or rich bastards to explain why the project’s worthy of funding, a triple cross between mission statement, PR release and abject apology. There ought to be a prize for projects whose success comes from escaping the initial proposal; maybe there’s an emoji for that. And if, as in this case, the project doesn’t fully succeed, it’s because the original concept is so rich and the bar so high.

The Cooper Hewitt show is structured as a kind visual contest, pitting Du Bois’ contribution against those objects and styles that are most representative of the Universal Exhibition, the apotheosis and Götterdammerung of the Art Nouveau style. The Cooper Hewitt houses the personal holdings of Hector Guimard, the designer of the Paris Metro entrances. Highlighting the Permanent Collection’s always a plus in your application.

Willowy organic curves against pared-down, factual graphs: it’s the old Contrast-and-Compare routine from your introductory course in Art History, and it’s handled here with all of the sophistication of a freshman paper. Somehow, the signage suggests, the sinuous lines of Art Nouveau evoke (excuse me: “reference”) the slave-master’s whip, supposedly because the Art Nouveau style was somewhere described with a whip metaphor. That’s seriously ridiculous, this fantasy that it’s shapes that determine ideologies, instead of the other way around. It’s the kind of drivel that sank the minor Cubists:

Art Nouveau was often called “le style nouille.” For you it’s fifty strokes with a wet one.

More serious, and less ridiculous, the curators have inserted the commonplace reading of the International Exposition as a monument to imperialism and racial subjugation, only they’ve inserted it where it doesn’t belong. Inexplicably, the show includes a small set of photographs documenting European brutality:

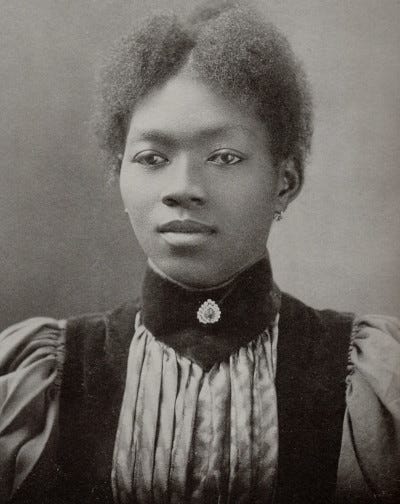

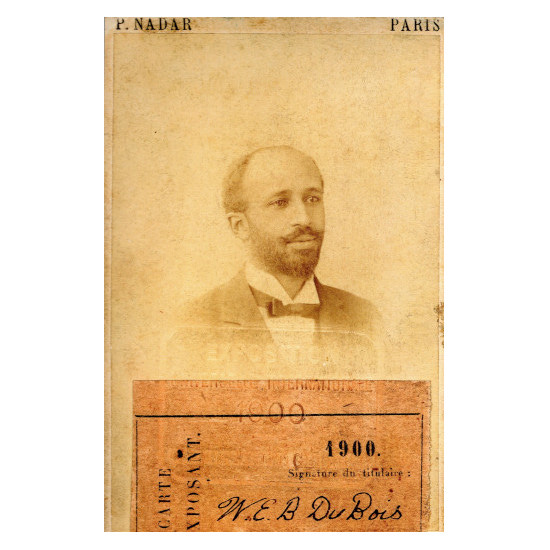

No one this side of Ron DeSantis could object to this particular narrative, except to point out that it hides and distorts Du Bois’ own intentions. The original Exhibit of American Negroes included a selection of photographs of African Americans, presumably taken by Du Bois himself:

These images have a constant: the calmness, the gaze, the sense of the capable and upstanding. Hardly a downtrodden caste. The curators’ choice not to include them, and to replace them with images of Black suffering, reminds me of a comment of Frantz Fanon, in The Wretched of the Earth, that many liberals enjoy jazz—it could be rap today—because the forms “are faithful to this arrested image of a type of relationship,” meaning some people prefer the image of a downtrodden, revengeful, unstable Black to the picture of civic and social maturity privileged by Du Bois.1 Surprising as it may seem, many Black people do not particularly enjoy being defined by “Slavery Times,” any more than Jews like to find themselves exclusively defined as victims of the Churban [Holocaust].

There is another, somewhat trivial, explanation for the inclusion of these photographs and the exclusion of Du Bois' own: scholars of late have tried to diminish Du Bois' Marxist and Socialist side by insisting on his Pan-African side; the argument revolves around varying definitions of European Imperialism, Du Bois' and the Marxist. Whatever his Marxism, in 1900 Du Bois was a Professor of Sociology, and it's hard to imagine anyone in that position who was not informed about Marxist and Social-Democratic theorizing. The 1900 project was resolutely social, and resolutely local in the political sense: it focused on African Americans, not Africans. Du Bois' original photographs, too, are consistent with the argument he would develop in response to the celebrated Black leader Booker T. Washington a few years later. Washington, Du Bois believed, was too quick to deny that African Americans were ready for full participation in American social, political, and cultural life. The photographs prove the contrary, and they prove it in the most aesthetic manner. Additionally, Washington's famous "Atlanta Compromise" speech, the same speech against which Du Bois vehemently took sides, had been delivered at the Cotton States and International Exposition five years before the Paris Exposition.2 Payback time.

Humanist education — aesthetic education— was a one of the three major elements of Du Bois’ program, as described in The Souls of Black Folk. Aesthetic sophistication was not merely an adjunct to social achievement, it was part and parcel of that achievement; self-empowerment and leadership were not possible without it. To what extent was Du Bois consciously following European and Social-Democratic thought on that point? I wish I had the answer. Suffice to say, the aesthetic and the social were tightly bound in the Paris show, only not in the way the curators imagine. In terms of its aesthetics and design, Exhibit of American Negroes is not so much in opposition to Guimard’s “noodle” style, it’s in advance. Guimard himself would shortly switch to a more restrained, linear, and yes, social approach, to the point of designing low-income housing units.

What’s revolutionary about Exhibit is not merely the high level of its discourse, but that it proposes a model for a rational, visual, and humanitarian approach to the presentation of data that would not have been out of place a quarter-century later, alongside the exhibition spaces designed by Otto Neurath and El Lissitzky. Exhibition Design, too, has its distinctive place in the History of Design. From the Cooper Hewitt one should expect no less.

WOID XXIII-07

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, translated from the French by Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press, 1963), p. 93.

W.E.B. DuBois, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others,” The Souls of Black Folk. Writings (New York: Library of America, 1986, pp. 392-404.