Review

Palestinian Yiddish: A Look at Yiddish in the Land of Israel before 1948. YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research), Center for Jewish History, 15 West 16th Street, New York City, September 5 2023, through December 31. https://www.yivo.org/Palestinian-Yiddish

Access: Free.

“There is a long funeral procession that prevents me from crossing the street and going home.” Jean Cocteau

Crazy Zionist Grampa. He’s your crazy MAGA uncle, only Jewish. He hogs the Seder as your MAGA hogs Thanksgiving, he makes you cringe with his racist views.

And he’s been around for a long, long time. As a Jew, your life has been under the shadow of his pudgy finger, his accusations, his lies, his shouting you down. I met him, many years ago, in Ur-form, his name was Meir Kahane. If you’ve been shouted down by Meir Kahane you’re going to be very careful about what you do and what you say. Kahane got smoked but his progeny live on. Their name is legion. Violence doesn’t solve anything.

Imagine what it must have taken for Eddy Portnoy, Senior Academic Advisor and Director of Exhibitions at YIVO and the curator for Palestinian Yiddish, a short overview of Yiddish in Palestine and Israel.

YIVO (ייִדישער װיסנשאַפֿטלעכער אינסטיטוט, Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut), is the Library of Congress and Académie Française of the Yiddish Language. Like every other Jewish institution YIVO lives under Grampa’s shadow. In Palestinian Yiddish Portnoy tells the story of a language shouted down and almost bullied into oblivion. The מאמע לשון (Mame-loshn, Mother-tongue) has been in an abusive relationship with Zionism for the longest time.

The exhibition’s laid out clockwise, left to right, which is confusing because most viewers view an exhibition counterclockwise, but if you’re used to Yiddish you’ll be more comfortable viewing an exhibition in the reverse direction. The last part (moving clockwise) is the most important part: Hebrew as the Crazy Grampa of the Politics of Language. Time to pull the curtain on that nasty little man.

To begin at the beginning (if that’s where it’s at) we’re introduced to the basics of Yiddish-according-to-YIVO. Yiddish, we’re reminded, is a “fusion language,” meaning it adopts words from the speaker’s host country. (The expression is from YIVO’s founder, Max Weinreich.) Yiddish, I was taught in Yiddish School, is an Eastern European language, an overlay of Slavic words on top of Hebrew, German and some Medieval French, with a grammatical structure and pronunciation remarkably close, even today, to South German Vernacular. (That part I had to learn on my own.) The narrative begins to wobble as we’re shown a reproduction of a letter written in Yiddish, in 1567, from a Jewish mother in Palestine to her son in Cairo. It’s from Rachel Zussman (obviously a German Jewish name) to Moshe, complaining (what else?) he doesn’t write his mother. But why Yiddish, and why from Palestine? “Fusion” tells you what, not why.

Then comes Khayem Keler’s Arabic-Yiddish textbook of 1935, from a time when Jews were massively migrating to Palestine The purpose, according to the author, was “to allow us to come into contact with our neighbors, the Arabs, so that we may be able to understand one another.” We could use some of that.

Others obviously couldn’t. With the growth of Zionist muscle in the ‘‘twenties begins what the curator calls “anti-Yiddish terrorism.” Palestinian Yiddish speakers routinely “suffer[ed] verbal abuse and occasional physical attacks:”

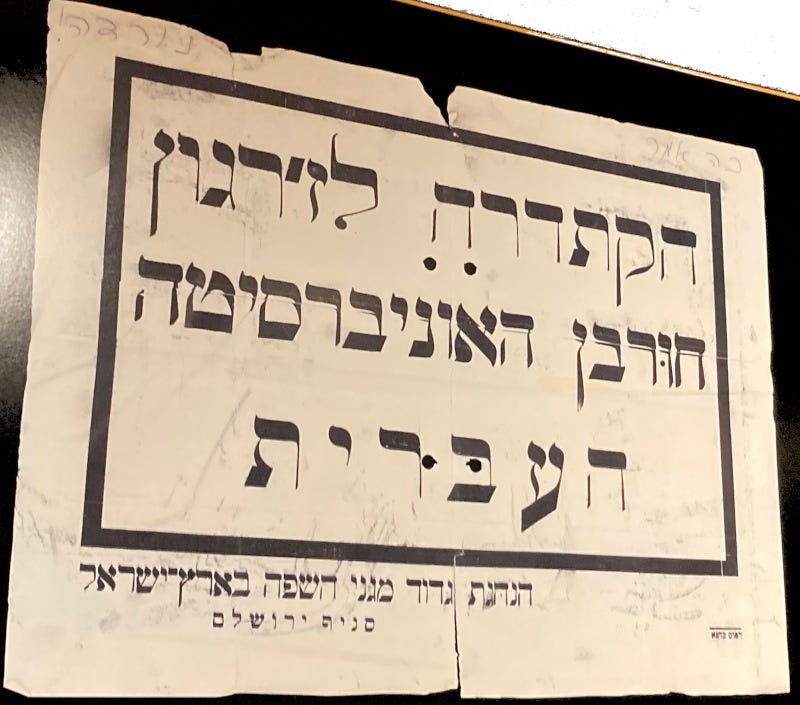

“Yiddish was denigrated by the official Zionist press, from proper newspapers like Ha'aretz to scandal sheets like Do'ar Hayam.” Yiddish-speaking immigrants were treated like “dust, like nothing.” One Zionist group, the “Language Defenders Battalion,” was given to tossing smoke bombs and stinkbombs in Yiddish theaters and movie-houses, closing down editorial offices by force and setting fire to newspaper kiosks. At one point Hebrew gangs broke up a meeting of the Association of Yiddish Writers and Journalists, smashed windows, and cut off the electricity: “We have to be fanatics.” Mission accomplished.

Like the Nazis back in Europe, the Zionist Übermensch focused on the universities and intellectuals. The eminent Yiddish writer Sholem Asch was met with protests on a lecture tour. When Khayem Zhitlovsky, a proponent of Yiddish Socialism, attempted to speak at a workers’ meeting he was blocked by a gang of teenagers egged on by their principal at an elite all-Hebrew high-school. Then someone pulled a gun.1 In a nice piece of inconsistency, those same bullies who harassed Yiddish-speaking academics and intellectuals denounced it as “the language of the masses.” No wonder Yiddish speakers felt an affinity with Arabs.

Even before the foundation of the State of Israel, a Yiddish speaker noted:

“Worse than the persecution was the methodical, psychological and ideological pogrom practiced by the authorities against the right to use the Yiddish language.”2

And this was carried over into the new regime:

“After the declaration of the State of Israel in 1948, the new government created legislation against Yiddish... intentionally trampling the heritage language of millions of Jews, a cultural tragedy that didn't have to happen.”

Except it did happen. Recently Shachar Pinsker, a professor of Judaic studies at the University of Michigan, was so distressed by the present conflict in Gaza he decided to translate from the Yiddish a short story that appeared in Di Goldene Keyt, (די גאָלדענע קייט), the leading organ of the Yiddish literati after 1949. The story, ניט פאַרגעס (“Don't Forget”), by Avrom Karpinovitsh, describes how a recently arrived Yiddish speaker at first decides he has no stake in the Nakba, and then decides to kill an Arab because… Shoah!

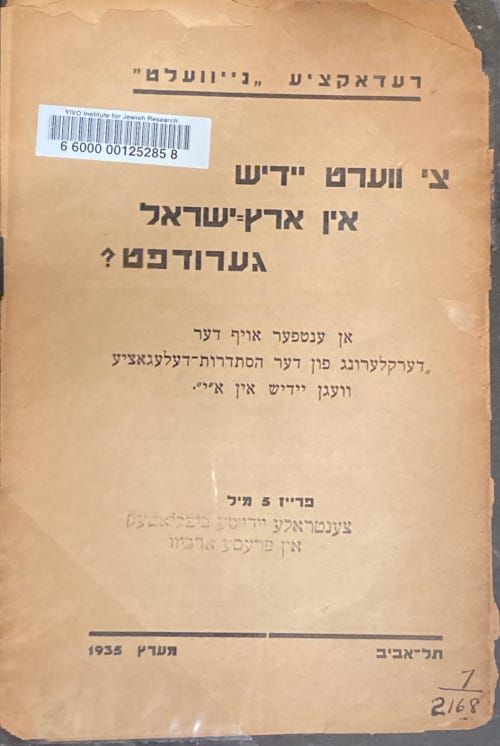

A common Zionist excuse. Not worthy of belief. Di Goldene Keyt was, early on, the only Yiddish publication allowed in Israel so long as it followed the Government line. In the ‘fifties Di Goldene Keit was under the supervision of the Histadrut, Israel’s central labor organization, whose tender concern for the language even before the foundation of the State of Israel is documented in the YIVO show:

In 1935 Histadrut, ever true to its apologist mission, sent a delegation to the US to reassure American Jews that Yiddish was not persecuted in Israel. In response the authors of the pamphlet shown above printed detailed evidence that Zionist institutions were pressuring concert halls, theaters, printing presses and labor unions to eliminate Yiddish from their activities. “Don't Forget” is, in fact, an injunction to forget, among other things, the parallels between the Zionist treatment of Arabs and the Zionist treatment of Yiddish speakers. Karpinovitsh’s story suggests the Nakba was, and is, if not justified, at least explained as a reaction to the Holocaust—or rather, the Churban. Churban [חֻרְבָּן] is the original expression used in Hebrew and Yiddish to refer to the extermination of Jews in 20th century Europe as a historic event, based on historic factors and therefore subject to human agency and responsibility. Holocaust has been in use since the 1950s to suggest a metaphysical, transhistorical dimension to the event; and act of divine, not human, agency. By absolving the Yiddish speaker of all responsibility, the text implicitly absolves all Hebrew speakers of their own. Palestinian Yiddish is a strong corrective to an argument I myself had long followed: that the cruelty, the arrogance, the murderous meanness of Crazy Zionist Grampa could be explained at least in part as a reaction to the Churban. As Zygmunt Bauman argued,

“The Jewish state tried to employ the tragic memories as the certificate of its political legitimacy, a safe-conduct pass for its past and future policies, and above all as the advance payment for the injustices it might itself commit.”3

As Yiddish Palestine demonstrates, the cruelty, the meanness, the arrogance long predated the Churban. As with Crazy MAGA Uncle, so, too, Crazy Zionist Grampa: neitherwas made mean in reaction to historical events, historical events only empowered them.

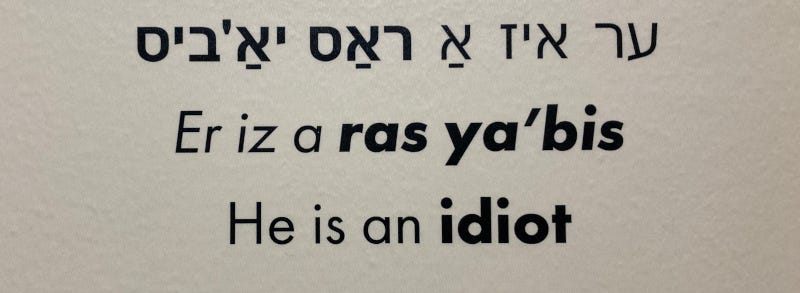

And the beast goes on. In 1967, Israeli soldiers entering Gaza were surprised to find the residents conversing with them in Yiddish, a language these speakers of Arabic had learned from their close interactions with the Jewish residents of Old Jerusalem. The fact, of course, was suppressed in Israeli narratives. That’s unfortunate, as there’s an expression from the Yiddish of Old Jerusalem, (a fusion of Yiddish and Arabic), that fits Grampa to a T:

WOID XXIII-29B

October 15, 2027; revised October 22, 2023.

Daniel Edelson, “'Zionism was a revolution, and revolutions have victims - one of these victims was Yiddish'.” YNET, September 17, 2023; https://www.ynetnews.com/article/hk4w9snkp, accessed September 14, 2023.

Zach Golden, “How Yiddish became a ‘foreign language’ in Israel despite being spoken there since the 1400s,” Forverts, September 11, 2023. https://forward.com/forverts-in-english/560390/how-yiddish-became-foreign-language-israel/; accessed October 14, 2023.

Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1992), p. ix.

A thrilling read!