III] Commentary

3]

“Conscience... that stuff can drive you nuts.” On the Waterfront.

In his doctoral dissertation on The Concept of Art Criticism in German Romanticism, a young Walter Benjamin wrote:

“One difference between the Kantian concept of the Critique of Judgment and the Romantic concept of Reflection easily suggests itself […]: Unlike Judgment, Reflection is not a subjectively reflective response; rather, it stays embedded in the work’s own form of representation.”

„Ein Unterschied zwischen dem Kantischen Begriff der Urteilskraft und dem romantischen der Reflexion läßt sich […] unschwer andeuten: die Reflexion ist nicht wie die Urteilskraft, ein subjektiv reflektierendes Verhalten, sondern sie liegt in der Darstellungsform des Werkes eingeschlossen“1

Here Benjamin confronts Kant’s systematic theorization of the purpose of Art with a Romantic aesthetic of completion. This is Benjamin’s way of suggesting that the meaning of a work of art is innate to the process of its creation, “embedded in the work’s own mode of representation” – “organic,” we might say today. For Benjamin the role of the critic was not to discern in the narrative the correct reflection of an objective idea but to clarify the artist’s agency in a common project, much as Heller had attempted to do for Kollwitz. It would not be out of place to designate his review as an early, accidental example of immanent critique, that staple of the Frankfurt School.

For Kant it was a reverse process: moral lessons, being universal, must issue from an abstract concept, the more abstract the better:

“I declare: the Beautiful is the symbol of what is morally good; and it is only in this respect […] that it pleases; […] whereby the mind is at the same time conscious of a certain ennoblement and elevation above the simple receptivity of a pleasure through sensory impressions.”

„Nun sage ich: das Schöne ist das Symbol des Sittlichguten; und auch nur in dieser Rücksicht […] gefällt es […], wobei sich das Gemüt zugleich einer gewissen Veredlung und Erhebung über die bloße Empfänglichkeit einer Lust durch Sinneneindrücke bewußt ist.“2

For Kant the moral sense of individuals did not arise from their sensual apprehension of the World. It was a rational response to the passive contemplation of the Idea of Beauty: You must change your life, blah, blah.

Kant’s argument was subverted by two influential works of Friedrich Schiller, The Theater Considered as a Moral Institution [Die Schaubühne als Moralische Anstalt betrachtet] of 1784, and the Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Mankind [Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen] of 1795. Both are concerned with moral improvement, except that morality now is anchored in the sensual activities of individuals in response to a rationalized ideal from above:

“It is not enough, therefore, for all intellectual Enlightenment to earn respect to the extent that it flows back into one’s character. Enlightenment also comes to a certain extent from character, because the way to the head must be opened through the heart. Training the ability to feel is therefore the more urgent need of our time.”

„Nicht genug also, daß alle Aufklärung des Verstandes nur insoferne Achtung verdient, als sie auf den Charakter zurückfließt; sie geht auch gewissermaßen von dem Charakter aus, weil der Weg zu dem Kopf durch das Herz muß geöffnet werden. Ausbildung des Empfindungsvermögens ist also das dringendere Bedürfnis der Zeit“.3

It might be intellectually fulfilling to contrast the two positions, Kant’s and Schiller’s, as if they involved Aesthetics in the narrowest sense. Except, by the late eighteenth century the category of the Aesthetic was so thoroughly embedded in German political and social life as to be inseparable from it. Neither Kant nor Schiller can be disassociated from the political implications of their aesthetics. To fully grasp the importance of the contrast between these two positions one must go back to social norms imposed on German-language speakers after the Treaty of Utrecht of 1648, with the establishment of two separate and compartmentalized worlds of thought, the one private, contemplative and devoted to personal belief, the other outer-directed, public, active in response to the demands of the local sovereign. Kant himself, to explain his theory of the sovereign power of Beauty, draws a parallel with the Sovereign in the political sense:

“Thus a monarchical state is represented by an animate body when it is ruled by the internal laws of the people, but by a mere machine [...] when it is ruled by a single absolute will.”

„So wird ein monarchischer Staat durch einen beseelten Körper, wenn er nach inneren Volksgesetzen, durch eine bloße Maschine aber […] wenn er durch einen einzelnen absoluten Willen beherrscht wird […] vorgestellt.“4

Kant offers little beyond a promise to reconcile the individual with their own conception of the Ideal. In contrast, Schiller offers each individual a glimpse of an autonomous moral existence anchored in the will. The dream of setting free each individual as an active, autonomous consciousness, regardless of class or even gender, would play a role in initiating the failed Bourgeois Revolution of 1848 in Germany:

“But whether we build something new or just digest the old as the cow digests the grass whether we create something in the world or just gaze at the world that makes a difference.”

„Aber ob wir Neues bauen oder Altes nur verdauen wie das Gras verdaut die Kuh ob wir in der Welt was schaffen oder nur die Welt begaffen das tut, das tut was dazu.“

The „Bürgerlied“ [Song of the Bourgeois, Song of the Citizen], “a document of the self-awareness of the Opposition” (Dokument des Selbstverständnisses der Oppositionsbewegung) in the years leading up to the Revolution of 1848, would be taken up by the Worker’s Movement of the late 19th century as a means to overcome that deeply rooted sense of political and personal powerlessness that is a distinguishing feature of Germanic cultures.5 Schiller’s dream of inner power was perfectly suited to the political idealism of Ferdinand Lassalle, Marx’s revolutionary rival, for what could be more empowering than the contemplation of the Revolutionary Idea?6 For Schiller’s conception of the Ideal as an instrument for self-awareness, Lassalle substituted a vision of the Ideal as a tool for political re-alignment. Marx suggested he had simply confused the two,

“whereby I charge you with ‘Schilling:’ with transforming individuals into mere conduits voicing the Spirit of the Age, your most significant error.”

„während ich Dir das Schillern, das Verwandeln von Individuen in bloße Sprachröhren des Zeitgeistes, als bedeutendsten Fehler anrechne.“7

This was not mere literary criticism on Marx’s part. Lassalle’s ambition to equate the sum of individual drives with some sort of single agency of the World Spirit would have a lasting effect on politics, on aesthetics, and on psychology — assuming one could keep the three apart.

Around the time when Heller’s review of Kollwitz came out, a private, comradely exchange took place in the correspondence of two old friends: Karl Kautsky, the leading theorist of the Second International, and Victor Adler, a co-founder with Kautsky of the Austrian Worker’s Party, then its leader, and no mean theoretician himself. In January of 1903 Adler wrote to Kautsky:

“Effectively, [Jean] Jaurès would need sensible leadership and counterweight. I don't think he's a troublemaker as you do, but he could be of very different use if some sensible, clear-minded person were any match for him. But everything you hear from the opposing side seems to contrast with his intoxicating talent.”

And concluded:

“In addition, I think that with (or in spite of) H[ugo] H[eller]'s help, die N[eue] Z[eit] is now more zesty than it last was.”

„Jaurès würde in der Tat vernünftig Leitung und Gegenwicht brauchen. Ich halte ihn keineswegs für eine Schädling wie du, aber er könnte ganz anders nützen, wäre ihm irgend ein vernünftiger klarer Mensch irgendwie gewachsen. Aber seinem berauschenden Talente gegenüber erscheint alles, was man von der Gegenseite hört.“

[…]

„Übrigens finde ich, daβ ob mit od trotz HH’s Hilfe die N.Z. jetzt wieder pikanter ist, als sie zuletzt war.“8

Jean Jaurès, the leader of the French Socialist Party, was noted for his organizing skills and oratory, rooted, or so the Germans liked to think, in charisma and passion above logic and reason: mere icing on the cake of a Marxist science. Adler for his part was far more deeply engaged than his German comrades with the irrational, the “Dionysian.”9 Heller, Adler suggested, had been handed a similar brief to spice up the Culture columns at Die neue Zeit.

Two years later Kautsky wrote in turn to Adler, but now their divergences had taken on a stressful cast. In August of 1904 a storm had broken over the International Socialist Congress in Amsterdam over the question of tactics, with Jaurès denouncing the Germans as cowards and the Germans denouncing Adler as a crypto-revisionist [„verkappter Revisionist“]. That Jaurès himself was a revisionist in the intended sense of the German leadership, was not in doubt. Jaurès was accused of promoting a peaceful and gradualist transition to Socialism, based on class alliances, rather than passively banking on the seemingly inevitable exacerbation of class conflict and the effect of similarly inevitable and escalating economic crises. In an attempt to soften the Germans’ criticism, Kautsky wrote to Adler:

“I have not yet discovered anything about Revisionism in you and in that respect, I am quite at ease. Anyone who has grasped Marx as well as you will not become a revisionist. […] In your politics, Aesthetics always play a defined role next to Theory. […] Adler the Politician has certainly opposed Jaurès sharply enough, but Adler the Aesthete [der Ästhetiker] can’t bring himself to open himself to reflection over such a splendid exemplar. Still, I don't believe there’s a revisionist Adler.”

„Von Revisionismus habe ich noch nichts bei Dir entdeckt und in dieser Beziehung bin ich ganz ruhig. Wer seinen Marx so gut begriffen hat, wie Du, wird nicht Revisionist. […] In Deiner Politik spielt neben der Theorie immer auch die Ästhetik eine gewisse Rolle […] Der Politiker Adler ist ja auch Jaurès scharf genug entgegengetreten, aber der Ästhetiker Adler kann sich nicht entschlieβen, für eine so prachtvolle Erscheinung die Versenkung zu öffnen. An den Revisionisten Adler aber glaube ich nicht.“10

Here again, “Aesthetics” meant a great deal more than an interest in Painting or Music. For Kautsky the concept occupied a theoretical middle space between orthodox Marxism as he understood it, and full-blown Revisionism. This was certainly borne out by Jaurès himself: for all of Kautsky’s insinuations of irrationality, the French leader was a graduate of the prestigious École nationale supérieure who had authored two doctoral dissertations, one “On the Lineaments of Socialism in Kant,” the other on “The Reality of the Sensual World.” Those interests alone would have branded Jaurès a revisionist, since Revisionists stood out by their open endorsement of Kantian philosophy.11A third clarification of Jaurès’ interest in Kant can be found in his well-known lecture on the “Conflict between Materialism and Idealism in the Concept of History” [1894], in which he contrasted two apparent irreconcilables in the actual practice of Socialists, corresponding to the two positions argued to be irreconcilable by Kant: an ethics based on phenomenal perceptions against one based on the Ideal. In the first case, historical change is driven by changes in the relations among producers that originate in underlying economic conditions:

“People are in motion [...] because the social system forged between them at any given moment in history by the economic relations of production is an unstable system that is compelled to transform itself.”

« Les hommes se meuvent […] parce que le système social formé entre eux, à un moment donné de l’histoire, par les relations économiques de production, est un système instable qui est obligé de se transformer. »

On this point Jaurès arguably was closer to Marx’s than his detractors: his approach was consistent with what Étienne Balibar has called

“Marx's authentic theory, the essence of his critique of economism: the primacy of social relations of production over productive forces.”

« La thèse authentique de Marx, l’expression de sa critique de l’économisme : le primat des rapports sociaux de production sur les forces productives. »12

However, Jaurès falls back into Kantian Idealism when he adds:

“Humanity carries within itself a preexisting idea of justice and right, and it is this preconceived ideal that it pursues [...] and when it sets itself in motion, it is not through the mechanical and automatic transformation of modes of production, but under the influence, obscurely or clearly felt, of this ideal.”

« L’Humanité porte en elle-même une idée préalable de la justice et du droit, et c’est cet idéal préconçu qu’elle poursuit […] et quand elle se meut, ce n’est pas par la transformation mécanique et automatique des modes de la production, mais sous l’influence obscurément ou clairement sentie de cet idéal. »13

Historical conjunctures changed; human nature did not; the nature brought into being according to Jaurès was a socialist nature, a truly human nature. Historical developments were not driven mechanically by economic factors at the base as the Germans would have it, nor by changes in relations among producers, as Balibar suggests. Rather, as a true neo-Kantian, Jaurès emphasized the eternally valid ethics of the “transcendental subject,” the individual whose decisions are free to the extent that they are free of mere sensual perception, in contrast with Adler, for whom the workers are moved by

“[a will] that’s been fired by their personal insight [Erkenntnis], nurtured and increased by the experience [Erfahrung] of their own individual existence.”

„[ein Will] der sich entzündet hat an seiner persönlichen Erkenntnis, der sich genährt hat und groß geworden ist durch die Erfahrung seines eigenen persönlichen Lebens.“14

The workers, according to Jaurès, could be moved by an “instinctual sense, blind perhaps, of socialist consciousness” [« l’instinct, peut-être aveugle, de la conscience socialiste »].15 For Adler, however, the workers were moved by the lessons of their actual lived experience — experiences in which the Party itself was happy to participate, a therapist to the political unconscious.

It is this primacy given to lived experience over theoretical concepts as a mover of History that made of Adler an Ästhetiker in Kautsky’s eyes, whereas, according to Kant, raw, lived experience was of no use for the ethical Bildung of Humanity, since raw, lived experience was inaccessible to the idealizing mind. Adler’s approach was similar to Heller’s when, in approaching Käthe Kollwitz, he raised the concept of Gefühlsinhalt as a logical possibility: affect as a motivator, a Tendenz on a par with any other.

This was not an easy concept to grasp in 1904 — even for the editors of a popular dictionary of philosophy:

“Aesthetic [noun] (from the Greek): means primarily the doctrine of knowledge through the senses.”

“Aesthetic [adjective]: in the broader sense means everything that falls within the purview of the Aesthetic, thus also the displeasing, the charming, the pretty, the cute, the comic, the ugly, the terrible, the tragic, the sublime, etc. In the narrower sense, however, aesthetic is merely the concept of the beautiful, the tasteful. Kant...”

„Ästhetik (gr.) heiβt zunächst die Lehre von der Sinneserkenntnis.“

„Ästhetisch heiβt im weiteren Sinne alles, was in Kreis der Ästhetik fällt, also auch das Anmutige, das Reizende, das Hübsche, das Niedliche, das Komische, das Haβliche, das Furchtbare, das Tragische, das Erhabene usw; im engeren Sinne dagegen ist ästhetisch nur das Begriff des Schönen, Geschmackvollen. Kant…“16

There is something Borgesian about this list, as if, like Borges’ infamous dictionary, it lacked a referential center. “The comic, the ugly, the terrible, the tragic,” and so forth are not sensations per se, they’re only manifestations of a response to sensual perception. The following edition of the same dictionary attempts to clean up the incoherence, without succeeding:

“Aesthetic (from the Greek αἰσθητός) = perceptible to the senses.”

„Ästhetik (g. von αἰσθητός) = sinnlich wahrnehmbar.“17

The Greek word points to the source for Kant’s dichotomy: to Plato’s original distinction between αἰσθητικός (what is sensed) and νοητός (what is known by the mind), a distinction far broader than that suggested by “aesthetic” and encompassing it as well. The “Aesthetic,” then, is nothing less than that which is not known by the mind, and this, clearly, was Kautsky’s intended meaning when writing to his friend and comrade. Adler, Kautsky claimed, had broken with the Kantian belief that knowledge and ethical behavior cannot proceed from feeling:

“The practical necessity of acting according to this principle, i.e., Duty, is not at all based on feelings [Gefühlen], impulses and inclinations, but simply on the relationships of reasonable beings to one another...”

„Die praktische Notwendigkeit, nach diesem Prinzip zu handeln, d. i. Pflicht, beruht gar nicht auf Gefühlen, Antrieben und Neigungen, sondern bloß dem Verhältnisse vernünftiger Wesen zueinander“18

Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals lays out what Kautsky would have found objectionable in Adler, in the “anarchist-bourgeois” opponents of Marxist orthodoxy, and in Kollwitz herself. To the sittlich-ästhetike, the “ethical-aesthetic” individuals, as Kautsky called them, moral rules and patterns of behavior were derived from sense perception, as against the Kantian doxa that moral rules were universal, attained through Bildung and reason. Neuropsychiatry has recently shown that sense perception and affect are linked.19 In this case, however, the linkage is merely syllogistic: both are seen as logical negations of rational, idealizing thought.

That was certainly the sense intended by Kautsky, and by orthodox Marxists. In the pages of Die neue Zeit the concept of the ästhetik is not so much ignored as kept in its proper place behind a theoretical cordon sanitaire: Heller’s Culture beat, the „Literarische Rundschau“. For instance, an article titled „Eine ethisch-ästhetische Geschichte der Pariser Kommune“ refers to a comparative study of motivation among the combatants of 1871; another, again in the Culture section, classifies Zola’s novel, L’Argent, as sittlich-ästhetisch, “morally/socially aesthetic,” an expression that makes no sense without a grasp of Kant’s Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten.20 “Aesthetic,” then, would refer to the subjectivity inherent in all social relations.

In 1911 Karl Vorländer, the preeminent authority on Kantian Marxism (and therefore an authority on Revisionism) carefully examined the first twenty years of Die neue Zeit before concluding that Kant “was touched upon only superficially in a very few places.”21 No doubt; but if the philosophical deity was nowhere visible, he was everywhere present. Most orthodox Marxists were crypto-Kantian, even in the process of attacking the Kantianism of others, and Kautsky was no exception. Mind and “Reason” where privileged: abstract theory over practical activity, the ontological over the epistemological. The issue was not the division between the two spheres of perception but the dominance of the one over the other. Reason was not so much instrumental as instrumentalized, an instrument of social legitimation.

It was against this primacy of the abstract that Engels took a position in his Preface to the English edition of The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science [1892]:

In Kant’s time our knowledge of natural objects was indeed so fragmentary that he might well suspect, behind the little we knew about each of them, a mysterious ‘thing in itself.’ But one after another these ungraspable things have been grasped, analysed, and, what is more, reproduced by the giant progress of science; and what we can produce, we certainly cannot consider as unknowable. To the chemistry of the first half of this century organic substances were such mysterious objects; now, we learn to build them up one after another from their chemical elements without the aid of organic processes.”22

Three years later Sigmund Freud would ask himself whether cognitive mechanisms, subjective in appearance, could be explained through science, before deciding that the tools were not as yet available.23

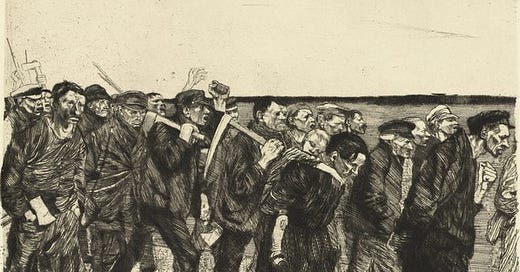

What we can produce, we certainly cannot consider as unknowable. The “thing in itself“ was not to be known in itself but through the activity of bringing it into being. Likewise, craft according to Kollwitz did not consist in the representation of affect but in the performance of affect, a performance she herself considered a form of ethics. Her intention was not to illustrate economic conditions presented as abstractions from direct experience, in the fashion of an article in Die Neue Zeit, but to rehearse in and for herself the affect engendered by those conditions. Affect was not dominated by the verbalization of affect but by the physical activity of the printmaker.

In concluding his survey of “Working-Class Culture and Modern Mass Culture before World War I,” Frank Trommler writes:

“The new role of aesthetic politics at the turn of the century cannot be overlooked. […] Of course, this approach calls for an equally expanded definition of the term ‘aesthetic.’”

Adding,

“There can be no doubt that Adler's strategy was quite different from the strategy of the German socialists. It was much more in line with the new awareness of mass psychology which grew at the end of the 19th century.”24

Nevertheless, a clear distinction needs to be drawn between “mass psychology” as a phenomenon apart, a form of group mentality, of “class consciousness,” as Marxists would say; and on the other hand a sum of dynamics rooted, as Adler put it, in

“A will within: a will that lives in every single individual, that’s been fired by their personal insight nurtured and increased by the experience of their own individual existence…”25

It was a distinction Freud would draw himself some sixteen years later, from a publishing house that Heller had helped to found.26 „Ein Mann über Bord!“, wrote Rosa Luxemburg as she watched Hugo Heller jump ship, from Stuttgart to Vienna, from Party loyalist to cultural impresario, gallery manager and publisher.27 It was more like coming on board.

WOID XXIV-11C

September 20, 2024

Part 3 of 3

Walter Benjamin, Der Begriff der Kunstkritik in der deutschen Romantik. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Bern, 1919 (Berlin: Arthur Scholem, 1920), p. 77.

„Der Schönheit als Symbol der Sittlichkeit“, Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft [Critique of Judgment], 1790, §59.

Friedrich Schiller, Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen in einer Reihe von Briefen [1795], Letter 8, paragraph 7.

Kant, ibid.

„Ob wir rote, gelbe Kragen,“ in Populäre und traditionelle Lieder. Historisch-kritisches Liederlexicon; https://www.liederlexikon.de/lieder/ob_wir_rote_gelbe_kragen; accessed September 5, 2024.

Giancarlo Buonfino, La politica culturale operaia: Da Marx e Lasalle alla rivoluzione di Novembre, 1859-1919 (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1975), passim.

Marx to Ferdinand Lassalle, 19 April 1859, in Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels, Werke, Vol. 29 (Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1978), p. 592.

Victor Adler. Briefwechsel mit August Bebel und Karl , ed. Friedrich Adler. Vienna: Verlag der Wiener Volksbuchhandlung, 1954, pp. 408, 409.

William J. McGrath, Dionysian Art and Populist Politics in Austria (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974), p. 221.

Kautsky to Adler, October 18, 1904, in Victor Adler. Briefwechsel mit August Bebel und Karl , ed. Friedrich Adler. Vienna: Verlag der Wiener Volksbuchhandlung, 1954, pp. 431, 434.

Peter Gay, The Dilemma of Democratic Socialism (New York: Collier, 1962), p. 151.

Étienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein. Race, nation, classe. Les identités ambiguës, 2e éd. (Paris : la Découverte, 1997), p. 10.

Jean Jaurès, « Idéalisme et matérialisme dans la conception de l’histoire », conférence de Jean Jaurès devant les Etudiants collectivistes, décembre 1894, salle d’Arras, à Paris. https://marxists.architexturez.net/francais/general/jaures/works/1894/12/jaures_189412.htm. Accessed September 11, 2024.

[Victor Adler?], »Vom Tage Wien, 28 November«, „Der Demonstrationstag“; see “Hugo Heller 💕 Käthe Kollwitz 2/2,” note 29, https://theorangepress.substack.com/p/hugo-heller-kathe-kollwitz-22

Jaurès, op. cit.

Kirchners Wörterbuch der Philosophischen Grundbegriffe, Vierte Auflage, ed. Carl Michaëlis (Leipzig: Durr’sche Buchhandlung, 1903), pp 13, 17.

Friedrich Kirchner, Wörterbuch der Philosophischen Grundbegriffe, fünfte Auflage, ed. Carl Michaëlis (Leipzig: Durr’sche Buchhandlung, 1907, pp. 16, Plato, Timaeus, 37a.

Emmanuel Kant, Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten [Groundwork for a Metaphysics of Morals, 1785], Zweiter Abschnitt. „Übergang von der populären sittlichen Weltweisheit zur Metaphysik der Sitte“.

Jaap Panksepp, Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Paul Lafargue, „»Das Geld« von Zola“, Die neue Zeit, X Jahrgang, erste Band (1891-92) p. 8; Karl Kautsky, „Eine ethisch-ästhetische Geschichte der Pariser Kommune“, Die neue Zeit XXIV Jahrgang, zweite Band (1905-1906), p. 351.

Peter Gay, The Dilemma of Democratic Socialism. Eduard Bernstein's Challenge to Marx (New York: Collier, 1962), p. 153, note 35.

Friedrich Engels, Socialism Utopian and Scientific. Translated by Edward Aveling with a special introduction by the author (London: Swann Sonnenschein & Co.; New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1892), xvii.

Sigmund Freud, "Project for a Scientific Psychology" [manuscript, 1895]; cf The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. I (London: The Hogarth Press, 1950), pp. 281-391.

Frank Trommler, “Working-Class Culture and Modern Mass Culture before World War I” in New German Critique, no. 29 (1983): p. 67.

cf. note 14, above.

Sigmund Freud, Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse [Mass Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego] (Wien: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, 1921).

Rosa Luxemburg, Gesammelte Briefe, Vol. 2, 1903 bis 1908. Second ed. (Berlin: Dietz, 1984), p. 200; see “Hugo Heller 💕 Käthe Kollwitz 2/2,” note 4. https://theorangepress.substack.com/p/hugo-heller-kathe-kollwitz-22