III] Commentary

The wrath that makes a poet is well placed to describe these abuses, or to take on the harmonizers as well, who either deny or prettify these abuses in the service of the ruling class.

„Der Zorn, der den Poeten macht ist bei der Schilderung dieser Mißstände ganz am Platz, oder auch beim Angriff gegen die, diese Mißstände leugnenden oder beschönigenden Harmoniker im Dienst der herrschenden Klasse.“ Friedrich Engels.1

“For what will nourish this strength, what will maintain this alacrity, is the image of the chained ancestors, not of an emancipated posterity.”

« Car ce qui nourrira cette force, ce qui entiendra cette promptitude, est l'image des ancêtres enchaînés, non d'une postérité affranchie. » Walter Benjamin.2

Most anyone who studies the art of Käthe Kollwitz — those passionate images of grief and social struggle — may well conclude her art is at once political and distinct from political art in the usual sense. What most distinguishes Kollwitz is her preference for process over outcome, a preference that operates in the twinned realms of narrative and technique, the two so closely tied as to reinforce one another.

Was it because of his close friendship that Hugo Heller grasped these aspects of Kollwitz’s art and personality? Was Kollwitz empowered through her closeness to Heller, intellectual and physical at once? Both, as we now know, were involved in a passionate affair. We don’t know when it started, though we think we know its end. Käthe's erotic drawings celebrating their relationship are usually dated 1909 or 1910, from the time Heller, after the death of his first wife, attempted to revive the relationship, most likely without success. Whatever the case, Heller’s review of Kollwitz, published in 1903 in Die neue Zeit, the organ of the Social-Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD), gives us a glimpse of the unity in Kollwitz’s creative production: unity of the affective, the political and the process, all in one. Much of what Heller describes in Kollwitz — a theoretical clarification of her own lived aesthetic challenges — would come to fruition decades later, in the thought of Adorno, Brecht and Benjamin.3

Heller himself had risen in the Viennese book trade as a labor organizer, book dealer and editor of left-wing populist journals. In 1900 he left for Germany at the invitation of Karl Kautsky, the leading theorist of the Second International, and joined Die neue Zeit as editor. He resigned in 1905; Rosa Luxemburg blamed his departure on Clara Zetkin, the great feminist revolutionary, while Heller’s 1923 obituary claimed his resignation was caused by the split between the revisionist wing of the Party and the radicals. The two are not mutually exclusive: Zetkin was equally intransigent in the realm of Culture and Party discipline, and Heller’s political outlook, like his life, was anything but dogmatic.4

Back in Vienna, Heller founded a radical bookstore where Arnold Schoenberg first showed his paintings, where Freud (whose Wednesday Psychological Society Heller had joined early on) gave his only public lecture, from which Heller would distribute Die Aktion, the radical journal that attempted to blend the aesthetic and the political — blend so closely as to make them indistinguishable. Subsequently Heller took on the task of publishing Freud and the journals of the International Psychoanalytic Association before turning impresario for people’s concerts.5

Whatever the details of their involvement, Heller’s review of Kollwitz is cordial and detached. Yet underneath we sense a profound intellectual harmony, a shared, complex and conflicted fascination with the intertwining of politics and affect in the production of art.

The twenty-odd years leading up to World War One witnessed intense debates on the Left, not only over the role of Art and Culture in bringing about Socialism, but over the type of art that could be expected to fulfill that role. Many — especially the faction indebted to Marx’s rival Ferdinand Lassalle — had taken up Friedrich Schiller’s romantic vision of Art as Erziehung, the internalization of the revolutionary spirit through Art and Culture, while the straight-and-narrow Marxists of the SDP fell back on the Enlightenment concept of Bildung, the formation of a well-rounded, well-adapted personality, fully functional in Society by way of a “lengthy effort toward the inner formation of the way of thinking of its citizens” [die langsame Bemühung der inneren Bildung der Denkungsart ihrer Bürger].6 The goal of Revolution, according to Wilhelm Liebknecht, a founder of the SDP, was the full integration of the worker into German Society and Culture under the tutelage of the Party. Likewise, only Socialism, according to Zetkin, could fully develop a woman’s natural calling to bear and educate her children in the interest of Society.7 Erziehung was an open process of growth from within; Bildung was the ultimate goal.

“‘Freedom through Bildung:’ that is the wrong message [...] Our answer: Bildung through Freedom! Only in a free people's state can the people achieve Bildung.”

„»Durch Bildung zur Freiheit,« das ist die falsche Losung […] Wir antworten: Durch Freiheit zur Bildung! Nur im freien Volksstaat kann das Volk Bildung erlangen.“8

At the 1896 Party conference in Gotha the Party brains (Wilhelm Liebknecht, Franz Mehring, Zetkin of course) ganged up on the Erzieher, the educators, by which, Mehring insisted, he did not refer to “the tasteless and disgraceful mentoring by the anarchist-bourgeois confusion-councils” [dem abgeschmackten und anmaβenden Präzeptorenthum der anarchistisch-bürgerlichen Konfusionsräthe], but to well-meaning but ultimately futile productions like Gerhart Hauptmann’s play The Weavers. While granting good intentions, Mehring argued that Modern art was not the appropriate handmaid to the Arbeiterbewegungkultur, the wished-for culture of the Worker’s Movement, which, according to Mehring, must be realistic rather than poetic; informative, not performative; optimistic, not tragic; analytical, not utopian; outer-directed, not self-involved; scientific knowledge against subjective experience:

“Every revolutionary class is optimistic. [...] This, of course, has nothing to do with any kind of utopianism. […] Modern art, on the other hand, is deeply pessimistic. It knows no way out of the misery it loves to depict. [...] ”

„Jede revolutionäre Klasse ist optimistisch. […] Das hat selbstverständlich mit irgend welchem Utopismus nichts zu thun. […] Dagegen ist die moderne Kunst tief pessimistisch. Sie kennt keinen Ausweg aus dem Elend, das sie mit Vorliebe schildert.“9

Rational above all. Art, according to the bureaucratic Marxists of the SPD, was only the reflection of the base structure. It could never, as Schiller suggested, modify the economic and political substrate of bourgeois Society. Zetkin:

“Only after Labor breaks frees from the yoke of capitalism, after class antagonisms in society are transcended, only then does the freedom of art take on life and form…”

„Nur wenn sich die Arbeit vom Joche des Kapitalismus befreit, nur wenn damit die Klassengegensätze in der Gesellschaft aufgehoben werden, nimmt die Freiheit der Kunst Leben und Gestalt an…“10

Because art could not change anything—neither the individual nor Society — the historic task of the artist was the depiction of those events and attitudes the Party deemed to be proof and illustration of the inevitable triumph of the Class Struggle. Writing for the official organ of the SPD, Heller took up the Party Line and twisted it to his own ends, hinging his argument on the slippery meanings of the shape-shifter word Tendenzkunst, “art with a tendency,” “art with a bias,” “art with a message,” and the message implicitly political: the French today would call this art engagé, “art with a social commitment.”

With an emphasis on social. By the end of the 19th century the Aesthetic Movement had begun to affirm the claims of “pure” art, Art for Art’s Sake, by which was meant, not Art without commitment, but art committed to the essence of art itself, as opposed to social and historical externalities. The movement was in ways a reaction to the growing threat of Socialism; for theoreticians of a socialist aesthetic it raised the question, whether any art was possible that did not refer in one way or another to an object or concept external to art itself. Even the boldest theoreticians of art dare not part with

“those elements of form or motif which are meaningful in a more cerebral sense, and of which [William] Morris says that ‘you may be sure that any decoration is futile, and has fallen into at least the first stage of degradation, when it does not remind you of something beyond itself, of something of which it is but a visible symbol.’”11

Like most of the assumptions that constituted aesthetic thought in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the concepts brought to bear on the signifying content of a work of art had been determined eis aiona in Immanuel Kant’s Kritik der Urteilskraft [Critique of Judgement] of 1790:

“In all of the fine arts the essence [das Wesentliche] lies in the form, whose usefulness is for observation and judgment; whose pleasure is simultaneously that of Kultur; which harmonizes mind and Idea, thus making the mind receptive to several such pleasures and diversions; crude in matters of feeling [Empfindung] (stimulus or emotion), when it is designed merely for pleasure and leaves nothing to the Idea.”

„In aller schönen Kunst besteht das Wesentliche in der Form, welche für die Beobachtung und Beurteilung zweckmäßig ist, wo die Lust zugleich Kultur ist und den Geist zu Ideen stimmt, mithin ihn mehrerer solcher Lust und Unterhaltung empfänglich macht; dicht in der Materie der Empfindung (dem Reize oder der Rührung), wo es bloß auf Genuß angelegt ist, welcher nichts in der Idee zurückläßt.“12

Kant did not object to narrative content itself which, he admitted, was indispensable in order to “make the mind receptive.” Rather, Kant and his bourgeois progeny felt privileged to reject specific types of narrative, say, those that argued for World Revolution or a change in individual consciousness, while endorsing narratives that referenced the Idea, das Geistige, the “Spiritual,” the province of the Mind and Soul.

Aesthetic debates in turn-of-the-century Germany cannot be reduced to a theoretical conflict between proponents of “Art-for-art’s sake” and proponents of “Art-for-the-sake-of-something-external-to-art.”13 Rather, they overwhelmingly involved a disagreement as to what that external something was. Heller was merely following the Party Line in Art when he suggested that the term Tendenz could be applied to all sorts of art promoting all types of narrative. Zetkin again:

“It is not the ‘tendency’ in general that is condemned in the name of art, only the ‘tendency’ that contradicts the ‘tendency’ of the ruling classes. What else is tendency but an idea? Art without an idea, however, becomes artifice, artistic formulaic stuff.”

„Nicht die »Tendenz« überhaupt tut man im Namen der Kunst in Acht und Bann, nur die »Tendenz«, welche der »Tendenz« der herrschenden Klassen widerstreitet. Was anders denn ist die Tendenz als Idee? Kunst ohne Idee aber wird zur Künstelei, zum künstlerischen Formelkram.“14

All the same, there was widespread agreement among the social realists of the SPD, the idealizing bourgeois idealists who opposed them, and the self-described proponents of Art for Art’s Sake as well: that the sensual, non-rational, affective component of art was distinct from its rational, mental, mindful content. This belief was rooted in Kant’s distinction between the phenomenal and the noumenal: between that part of the mind that grasped and manipulated the world by means of concepts, and the part that merely received the impressions of the senses and had no analytical function. Heller breaks with all this with the unusual expression he brings to bear on Kollwitz’s art: Gefühlsinhalt, literally: “feeling-content.”

This paradoxical expression (paradoxical from the Kantian point of view) had been applied in mid-nineteenth century Music Theory. Music was the one art form that most puzzled Kant, and most intrigued the Symbolists and the Art-for-art’s sake crowd: Music, in which Kant discerned no content at all, “for it speaks by means of pure sensations without concepts.” [Sie zwar durch lauter Empfindungen ohne Begriffe spricht].15 From there the expression passed to those other forms that could be said not to sustain a narrative; for instance, architecture. In 1918 an architectural theorist felt the need to clarify the meaning of

“Feeling-content,” the psychic content of the work of art, inasmuch as it is not given by association, but has been implicitly made to emerge directly alongside of the subject.”

„ … den Gefühlsinhalt, den seelischen Gehalt des Kunstwerkes, soweit er nicht assoziativ, sondern implicite, mit dem Sujet direkt verwachsen gegeben ist…“16

Gefühlsinhalt, then, is the affective reaction to the content that the performer — of music, architecture, or a visual art — brings to the performance. Gefühl is no longer external to the work; rather, it’s an integral component of the construction of the work. The term seems to originate in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s theory of language, in which the inflection associated with the vocal performance of words and concepts is necessary in order to convey their emotional content; likewise in architecture one might consider Borromini’s dome for San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome, a work of enormous impact on South German architecture, in which the mechanical constraints in the process of construction are the tragic restraint upon the Divine Light that threatens to flood and obliterate the structure:

In the early ‘sixties a relative who’d spent some time in the newly-created Republic of Mali came back with an outraged reflection. She’d spoken with a local intellectual who’d asked her, “when you listen to Chopin, what stories do you hear?” To her the belief that a piece of music might have a story (Inhalt) verged on the barbaric. To the critics and aesthetes and revolutionaries of art in Germany, likewise, Gefühl was mere icing on the cake of art, it could never be intrinsic. In 1898 Kollwitz’s Weavers series was submitted without her knowledge to the Great Berlin Art Exhibition [Große Berliner Kunstausstellung]. The German Jewish Impressionist Max Liebermann, who sat on the Jury, had, he later wrote, pushed through [durchgesetzt] an award for Kollwitz, the “small gold medal;” likewise the preeminent realist painter Adolf Menzel.17 However, under the rigid system of State patronage of Wilhelmine Germany the decisions of the Jury were merely advisory; on June 12, 1898 the Minister of Culture, Robert Bosse, wrote to his boss the Kaiser, Wilhelm II, the ultimate fount of cultural largesse:

“The artistic accomplishment in her technique, as well as the strength and energy of her expression, might well [mögen] seem to allow for justification of the Jury’s decision — from a pure artistic standpoint. From the angle of subject represented and the naturalistic execution of the work, however, which entirely lacks any mitigating or conciliatory element, I do not believe it should be recommended for explicit recognition by the State.”

„Die technische Kunstfertigkeit in dem Werk sowie die Kraft und Energie des Ausdrucks mögen das Urteil der Jury vom rein künstlerischen Standpunkt aus gerechtfertigt erscheinen lassen. Bei dem Gegenstand der Darstellung und der naturalistischen Durchführung des Werkes, welchem ein milderndes oder versöhnendes Element gänzlich fehlt, glaube ich aber nicht, dasselbe zu einer ausdrücklichen staatlichen Anerkennung vorschlagen zu dürfen.“18

To Bosse “the strength and energy of her expression” was incidental, mere icing. True content (in the Kantian sense) must lie in the “Idea,” the ideal message, and Kollwitz’s message, according to Bosse, was inappropriate. The “mitigating or conciliating events” that Bosse found missing were those symbolic images, diaphanous victories or rays of sunshine haloing the hero’s head, that were a sine-qua-non of official art, its Geistige content.

A year after her rejection and most likely in reaction to it, Kollwitz inserted an allegorical figure into her representation of a brutal peasant uprising:

Not that the Minister would have approved of this new, unusual incarnation of the Idea; nor the Party. Kollwitz’s allegorical figure is discordant, not as a figure of discord but as an allegorical figure charged with a discordant message. This strategy of overloading a figure with a conflicting or contradictory affective message would become a commonplace for Kollwitz, a libidinal suppression of pleasure for which Heller himself would eventually pay the price. One may think ahead to Freud’s contested argument for the existence of a Death Instinct; or backwards, to Baudelaire’s insistence on the fundamental contradiction between the world of symbols and the world as experienced.19

Kollwitz’s message, more concerned with proletarian despair than proletarian hope, was not acceptable to either camp: neither to Socialist theoreticians, nor to those who wished to find uplifting spirituality and instead found in her art a disturbing attention to darkness and despair. Fortunately, the German Emperor had a knack for uniting disparate groups in opposition to himself. Already the Kaiser had managed to unite the two irreconcilable wings of the feminist movement, the bourgeois and the proletarian, by declaring that women were not deserving of awards to begin with.20 Then in December of 1901 the Emperor inaugurated a grotesque series of heroic and patriarchal statues along the Siegesallee, the avenue that cuts through the heart of Berlin. The Kaiser’s inaugural speech was an implicit threat as well, directed at the type of art that, he claimed, belonged in the gutter (Rinnstein):

“Now if art, as so often happens, does nothing other than representing suffering as more hideous even than it is already, then it sins against the German People. The cultivation of the Ideal is presently the greatest task of Culture; if we want to be and to remain a model for other nations, our whole nation must co-operate.”

„Wenn nun die Kunst, wie es jetzt vielfach geschieht, weiter nichts tut, als das Elend noch scheußlicher hinzustellen, wie es schon ist, dann versündigt sie sich damit am deutschen Volke. Die Pflege der Ideale ist zugleich die größte Kulturarbeit, und wenn wir hierin den anderen Völkern ein Muster sein und bleiben wollen, so muß das ganze Volk daran mitarbeiten.“21

In short order the Kaiser’s “Gutter-Speech” [Rinnsteinrede] threw artists of previously limited political commitment into the arms of the Opposition, uniting all kinds of disparate elements. Rinnsteinkünstler [“Gutter-artist”] was now a badge of honor, borne as easily by Medieval Goliards and modernist miserabilists; and by Kollwitz herself.22 Once again the hoary meme of the artist as a revolutionary comrade-in-arms was dusted off, and the name of that camaraderie was “Expressionism.”

In Germany however the camaraderie was for the most part one-sided. Party theorists might grant that certain artists displayed the proper Tendenz, even if they were not Party members, but the true connection with the workers, they insisted, was to be found in the classics of German Literature and thought, the Bildungsmasters of Old, not among the Erzieher of the day. As late as 1938 Ernst Bloch complained that “The opposition of Expressionism versus, let us say, the Classical Heritage” was just as inflexible from one side of the debate as the other.23

In 1886 Friedrich Engels had closed his brief on the German intellectual tradition with the announcement that “the German worker’s movement is the heir of Classical Philosophy.” [Die deutsche Arbeiterbewegung ist die Erbin der deutschen klassischen Philosophie.]24 To the Party theoreticians this served to confirm their repeated claims for the precedence of rationalism (or “Geist”) over concrete worldly activity, noumen over phenomena. To be “rational” meant adhering to the Party Line; adhering to the Party Line made one rational. Tendenz could be validated only by the tenets of Marxist “science.” Meaningful content was to be found in Thought alone. Even today, what passes for Critical Theory is yesterday’s Bildung under another name, the field of perpetual graduate students who imagine “being a Socialist” consists in squeezing the Ideal out of every encounter with the World. Contrariwise, for a whole generation of Marxist theoreticians down to the ‘thirties the acceptance of a constructive role for affect and spontaneity in the building of Socialism was a major point of contention.

It’s important to be reminded that “role” is not “content.” The standard Symbolist procedure, which was to become the standard Expressionist procedure as well, was to attach “a message” to the text or object or, among the Symbolists, the shape or color. The formal elements of art had no moral or didactic value in themselves; at best they might serve to “attune the mind to ideas.” Clement Greenberg, the Cold-War neo-Kantian, used the same approach in 1945 in a review of Kollwitz published shortly after her death: Inhalt on one side, Gefühl on the other. Affect to Greenberg was merely a system for the proper adjustment of content:

“The passion inspired in her by her theme required a complementary passion for her medium, to counteract a certain inevitable excess.”25

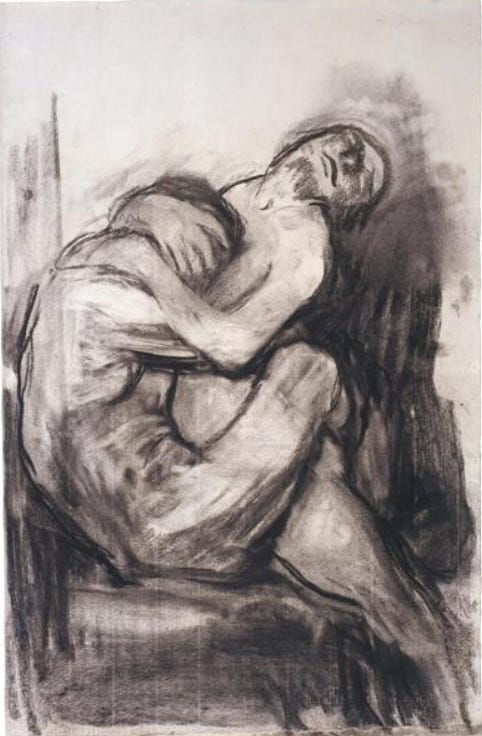

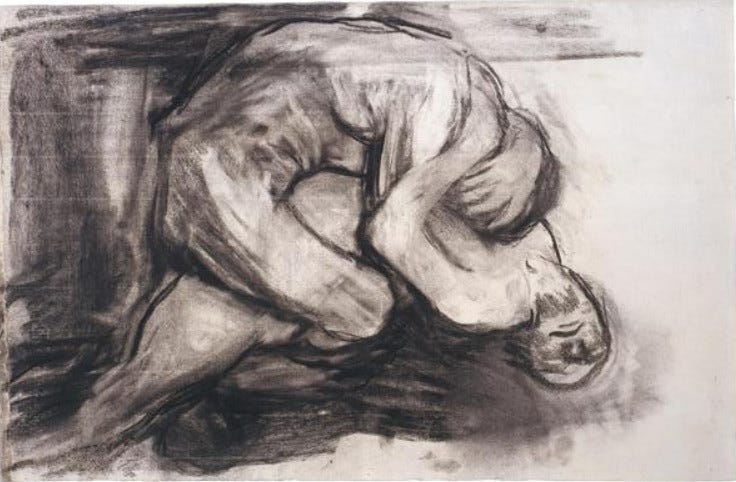

Greenberg’s description has parallels in the Systems Theory approach that still dominates Sociology and Ego Psychology in America: both focused on balance, stasis, adaptation — in one word: Bildung. Compare this with Kollwitz’s commitment to Erziehung: expansion from within, the perpetual off-balance of pain. With Kollwitz, Inhalt is Gefühl. Content is what is felt. Kollwitz compulsively reworked and modified her plates and drawings, working by erasure, superimposition, repetition, in a constant process of reinvention of affective response to ostensible content:

“Made a drawing: the mother who allows her dead son to slide [gleiten] through her arms. I could make a hundred such sheets and yet I don’t get any closer to him. I seek him. As if I were condemned to find him in the work.”

„Eine Zeichnung gemacht: Die Mutter, die ihren toten Sohn in ihre Arme gleiten lässt. Ich könnte 1000 solche Blätter machen und doch komme ich ihm so nicht näher. Ich suche ihn. Als ob ich ihn in der Arbeit finden müsste.“26

Gefühlsinhalt might be best described as the trace of the affective processing of the narrative content: a process equivalent, in psychonalytic terms, to the dream-work, the process of connecting, without loss of tension, the latent and the manifest content of the dream or projection. By 1903 Heller was likely familiar with the premises of Freud’s Traumdeutung [Interpretation of Dreams]: he joined the Wednesday Psychological Society that same year.

On June 28, 1921, Kollwitz entered in her diary,

“Saw The Weavers" at the Großes Schauspielhaus Theater. [...] Something of the feeling [Gefühl] I had when I first saw The Weavers came over me. [...] My childhood dream of falling on the barricades will be a hard one to fulfill. [...] Sometimes I don't even know if I’m a Socialist at all.

„Im Groβen Schauspielhaus »Die Weber« gesehn. […] Etwas von dem Gefühl, wie damals, als ich zum ersten Male die Weber sah, kam über mich. […] Mein Kindertraum, auf der Barrikade, zu fallen, wird schwerlich in Erfüllung gehen. […] Mitunter weiβ ich nicht, ob ich überhaupt Sozialist bin.“27

Belatedly, Kollwitz conceded her own old impulse to ground herself as “Socialist” or “revolutionary,” based on feelings alone; with the added suggestion that either entailed empathic suffering. This was the kind of attitude the German Socialists found unacceptable; the kind of affectation of empathy with which the Expressionists, in the tormented year that followed World War I, defined themselves:

Soon thereafter Kollwitz sold her etching press and turned to woodcuts and sculptures. Her work remained as politically committed as ever, but her commitment was expressed through narrative, less so through process. It was a new commitment to party program over feeling. With this Kollwitz repudiated her previous commitment, a commitment that relied on a sort of syllogism between Tendenz as political involvement and Tendenz as emotional investment; a view of the artist as dominated (beherrscht) by a kind of inner emotional necessity, similar to the economic necessity that drives the Proletariat in the Marxist telling. Tellingly, a few years after Heller’s review the word “Tendenz” would surface as a term of art in Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten (Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, 1905), in which Freud draws a distinction between “tendentious” (tendenziöse) and “non-tendentious” (nichttendenziöse) jokes, jokes that hurt and jokes that don’t; jokes designed to provoke emotional involvement (often sado-masochistic) on the hearer’s part, and jokes that merely involve word-play, the way Abstract Art art involves mere play of line and color. Freud calls the latter type of joke “abstract” (abstrakte). You can’t make this up.28

“We are far from proclaiming him a Socialist. […] But he felt the cutting contradictions in our society.”

„Wir sind weit entfern davon, ihn als Sozialisten zu proklamiren.[…] Aber er fühlte die schneidenden Widersprüche in unserer Gesellschaft“29

Written in 1889, Victor Adler’s obituary on the death of the Austrian playwright Ludwig Anzengruber cast a long shadow into the twentieth century.

Starting with Heller. The author of Anzengruber’s obituary was Victor Adler, founder, first chair and guiding light of the Austrian Social-Democratic Party of Austria (SDAP, Sozial-Demokratische Arbeiter Partei). Heller counted Adler as the second greatest influence on his life after Freud; Anzengruber may have been the third.30 Adler’s Anzengruber obituary was taken up as a manifesto of sorts by David Josef Bach, first music critic, then head of the Culture desk at the Arbeiter-Zeitung before heading the Sozialdemokratische Kunststelle (“Social-Democratic Arts Council”) in that vibrant period of cultural and social expansion known as “Red” Vienna (1919-1934). Bach’s influence on Theodor Adorno is incalculable for the simple reason that it’s never been properly calculated.

Here’s a drawback of the German language: because all nouns are capitalized it’s impossible, without additional explanation, to distinguish between a “Socialist” (meaning a member of a party that defines itself as such) and “socialist,” meaning a member of an emotional community that adheres broadly to the ethics and practices of socialism, an association

“…that constitutes itself naturally out of the grounds of modern Society… a party in the broad historic sense.”

„…die aus dem Boden der modernen Gesellschaft überall naturwüchsig sich bildet […] die Partei im großen historischen Sinne.“31

Anzengruber was no Socialist; , he was, however, as Adler suggested, an artist with a socialist affect; and affect, in turn-of-the century Vienna, played a decisive role in political organizing, a role that both the Left and the Extreme Right were eager to exploit. (Anzengruber would eventually be instrumentalized by the Nazis.)

In 1869 the influential Viennese physician and progressive politician Carl von Rokitansky theorized the concept of a Solidarity of Empathy (Solidarität des Mitleids); it was left to the young, politically involved intellectuals at the University of Vienna to theorize Solidarity through Empathy: solidarity of the cultured classes with the proletariat, of course.32 Empathy as a foundational aspect of the organization of the Working Class; Erziehung as the process of organizing empathy:

“This mass of the organised proletariat is not led by a will beyond its own, but by a will within: a will that lives in every single individual, that’s been fired by their personal insight [Erkenntnis], nurtured and increased by the experience [Erfahrung] of their own individual existence. [...] It is not drill, but self-discipline: the will of thousands joined in a collective will, the result not of coercion but a gigantic educational effort [Erziehungswerk] without equal."

„Nicht von einem Willen außer ihnen werden diese Massen des organisierten Proletariats geleitet, sondern von einem Willen in ihnen: der in jedem einzelnen lebendig ist, der sich entzündet hat an seiner persönlichen Erkenntnis, der sich genährt hat und groß geworden ist durch die Erfahrung seines eigenen persönlichen Lebens. […] Es ist nicht Drill, sondern Selbstzucht, es ist der zum Kollektivwillen vereinigte Wille von Tausenden, das Ergebnis nicht des Zwanges, sondern eines gigantischen Erziehungswerkes ohnegleichen.“33

The German Left called on the workers to achieve autonomy through Bildung—an autonomy which was little more than the autonomy of the Burger, the fully integrated and socially responsible bourgeois-citizen. In its stead the author of the article cited above (who may be Adler) proposes the mass performance of an autonomy that’s intrinsic to each individual. Freud, a great admirer of Adler, would take up the same argument years later in Civilization and its Discontents (Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, 1930).

The nature of the performance is radically different in Kollwitz; the procedure is identical: to work backward from the subject to an empathic grasp of the process of producing the subject, from the sight or sound of marching proletarians to the sensual sense of their actions. To the sensual sound as well: the process is similar to that of Adler’s protegé Gustav Mahler, who was to fulfill the same role for David Josef Bach that Anzengruber had played for Heller. In each case the role of the critic was neither to condemn the artist or the worker for colluding with the reigning powers, nor to praise them for inspiring narratives, but to reveal their true agency in a shared affect. With Kollwitz and Mahler the affect associated with the process of the construction of meaning substitutes for the meaning of narrative.34

„Ein Mann über Bord!“, wrote Rosa Luxemburg as she watched Hugo Heller jump ship, from Stuttgart to Vienna, from Party loyalist to radical cultural entrepreneur, a partisan fighter in the Popular Front of Culture. It was more like a coming on board.

WOID XXIV-11B

Part 2 of 3

Friedrich Engels, Herrn Eugen Dührings Umwälzung der Wissenschaft. Marx Engels Werke, Band 20 (Berlin: Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1975), p. 139.

Walter Benjamin, « Thèses sur le concept d'histoire -- Französische Fassung » in Über den Begriff der Geschichte, herausgegeben von Gérard Raulet. Walter Benjamin. Werke und Nachlaß, Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Band 19 (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2010), p. 66.

cf. Theodor Adorno et al., Aesthetics and Politics, (New York: Verso, 2010), passim.

Rosa Luxemburg, Gesammelte Briefe, Vol. 2, 1903 bis 1908. Second ed. (Berlin: Dietz, 1984), p. 200; „Hugo Heller gestorben“, Arbeiter-Zeitung (November 30, 1923), p. 6.

Paul Werner, “The Marxist Freudians. Introduction to The Fatherless Society” (The Orange Press, 2019), pp. 6-7. http://theorangepress.com/redviennareader/federn%20the%20fatherless%20society.pdf.

Immanuel Kant, Idee zu einer allgemeinen Geschichte in weltbürgerlicher Absicht, Siebenter Satz [1784].

Clara Zetkin, „Frauenarbeit“, Frauen-Beilage [Women’s Insert], Leipziger Volkszeitung , Nummer 33, 2 Jahrgang (20 September 1918), p. 263.

Wilhelm Liebknecht, „Wissen ist Macht, Macht ist Wissen“. Festrede gehalten zum Stiftungsfest des Dresdner Bildungs-Vereins am 5. Februar 1872. Neue Auflage (Berlin: Th. Glocke 1904), p. 52.

Franz Mehring „Kunst und Proletariat“ in: Die neue Zeit, 15. Jg., I. Band (1896-97) , pp. 32, 30, 29-30.

Clara Zetkin, „Kunst und Proletariat“, Die Gleichheit, Zeitschrift für die Interessen der Arbeiterinnen, Stuttgart, Nr. 7 und 8, 2. und 16. Januar 1911. https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/archiv/zetkin/1911/01/kunst.html

William Morris, “Some hints on pattern-designing” [Lecture, 1881], quoted in Frances B. Denington, The Complete Book. An Investigation of the Development of William Morris's Aesthetic Theory and Literary Practice. Doctoral Thesis, McMaster University (September 1975), p. 161; see also Joseph Masheck, “The Carpet Paradigm: Critical Prolegomena to a Theory of Flatness,” Arts Magazine, September 1976 (51:1), p. 101.

Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft [1790], par. 52.

Louis Marchesano, “Artistic Quality and Politics in the Early Reception of Kollwitz's Prints” in Louis Marchesano and Natascha Kirschner ed., Kathe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2020), p. 15, quoting from Christian Scholl, Revisionen der Romantik. Zur Rezeption der „neudeutschen Malerei 1817-1906“ (Berlin: Akademie 2012), 293-295.

Zetkin, op. cit.; Tendenzkunst-Debatte 1910-1912 : Dokumente zur Literaturtheorie und Literaturkritik der revolutionären deutschen Sozialdemokratie, ed. Tanja Bürgel. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1987.

Kant, op. cit., par. 53.

Herman Sörgel, Einführung in die Architektur-Ästhetik. Prolegomena zu einer Theorie der Baukunst (Munchen: Piloty & Loehle, 1928), p. 29.

Max Liebermann to Max Lehrs, 5 December 1901, thanking him for his essay on Kollwitz, presumably the same essay under review by Heller; quoted in Maria Derenda, Kunst als Beruf: Käthe Kollwitz und Elena Luksch-Makowskaja (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag 2018), p. 227, n. 39.

Peter Paret, Die Berliner Secession. Moderne Kunst und ihre Feinde im Kaiserlichen Deutschland, (Frankfurt a.M.: Ullstein, 1983), p. 37; see also Peter Paret, The Berlin Secession: Modernism and Its Enemies in Imperial Germany (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1980), p. 21.

Walter Benjamin „Über einige Motive bei Baudelaire,“ in Charles Baudelaire - Ein Lyriker im Zeitalter des Hochkapitalismus, Gesammelte Schriften I, 2, ed. Rolf Tiedemann und Hermann Schweppenhäuser (Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp , 2015), pp. 509-653; see also Theodor Adorno an Walter Benjamin, August 2, 1935, in Walter Benjamin, Briefe, ed. Adorno & Gershom Scholem (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1966), vol. 2, p. 676.

Annemarie Lange, Das wilhelminische Berlin. Zwischen Jahrhundertwende und Novemberrevolution (East Berlin: Dietz, 1967) p. 514; but see Peter Paret, Berlin Secession: Modernism and its Enemies in Imperial Germany (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980), p. 21.

Kaiser Wilhelm II „Die Wahre Kunst“ [„Rinnsteinrede“], Opening Speech, December 18, 1901.

Joan Weinstein, The End of Expressionism : Art and the November Revolution in Germany, 1918-19 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), p. 2. Weinstein gives no primary sources for her claim that Kollwitz was designated a “Gutter Artist.”

„Auch ist die Antithese: Expressionismus und — sage manklassisches Erbe bei Lukács genau so starr wie bei Ziegler.“ Ernst Bloch, Erbschaft dieser Zeit. Erweiterte Ausgabe (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1985), p. 265; see also Bloch, “Discussing Expressionism,” in Theodor Adorno et al., Aesthetics and Politics, (New York: Verso, 2010), p. 11.

Friedrich Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach und der Ausgang der Klassischen Deutsche Philosophie, in Marx-Engels Werke, Vol. 21 (Berlin: Dietz, 1962) p. 307.

Clement Greenbert, “Review of the Exhibition Landscape; of Two Exhibitions of Köllwitz; and of the Oil Painting Section of the Whitney Annual” (The Nation, 15 December 1945); .in The Collected Essays and Criticism. 2. Arrogant Purpose, 1945-1949 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), p. 46.

“August 22, 1916,” Käthe Kollwitz, Die Tagebücher 1908–1943, ed. Jutta Bohnke – Kollwitz (Munich: Siedler, 2007), p. 268. Note the concluding attempt at closure in the otherwise excellent analysis by Sarah Cowan, “Käthe Kollwitz's Sharpens her Tools,” Museum of Modern Art, March 27, 2024. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/1056.

Tagebücher, p. 88.

Sigmund Freud, „A. III. Die Tendenzen des Witzes“, Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten [1905].

Anon [Victor Adler], „Ludwig Anzengruber“, Arbeiter-Zeitung 13 (Dezember 1889), pp. 1-2. http://theorangepress.com/redviennareader/adler/Adler%20Ludwig%20Anzengruber%20%28English%29.pdf

Sabine Fuchs, Hugo Heller (1870 – 1923). Buchhändler und Verleger in Wien. Diplomarbeit, Fakultät der Universität Wien (2004), p. 67; Hugo Heller Gestorben, Arbeiter-Zeitung (November 30, 1923), p. 6.

Marx to Ferdinand Freiligrath, February 29, 1869. Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels, Werke, Vol 30 (Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1974), pp. 490, 495; reprinted in Die neue Zeit, Vol. 12 (1911-1912); cf. Eric Hobsbawm, How to Change the World. Reflections on Marx and Marxism, (Yale University Press, 2011), p. 60.

Carl von Rokitansky, Die Solidarität alles Thierlebens. Vortrag gehalten bei der feierlichen Sitzung der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften am 31. Mai 1869, in: Almanach der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 19, Wien 1869, pp 185–220; William J. McGrath, Dionysian Art and Populist Politics in Austria (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974), pp. 40-42, 214, etc.

Anon. »Vom Tage Wien, 28 November«, „Der Demonstrationstag“. Arbeiter-Zeitung. Zentralorgan der österreichischen Sozialdemokratie.Nr. 330, XVII Jahrgang (Mittwoch. 29 November 1905), p. 5.

Forest Randolph Kinnett, “Now his Time really seems to have come:” Ideas about Mahler's Music in Late Imperial and First Republic Vienna. Doctoral Disseration, University of North Texas (December 2009), pp. 33 sqq.